Sandra Bishop explores a tale of travels in the High Arctic from the NHSN’s Transaction

In the summer of 1881, thirty-year-old Abel Chapman set sail for Spitzbergen. It was a true Arctic adventure: six weeks of polar ice and midnight sun. Though he was not yet a member of the NHSN, Chapman later joined the society and published an account of his Journey to Spitzbergen, complete with sketches, in the 1880 – 1889 Transactions.

Chapman (1851 – 1929) was the grandson of Joseph Crawhall, one of the founding members of the NHSN. He spent his childhood on a country estate in Sunderland, surrounded by the traditional country pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing. After leaving Rugby School, Chapman joined his father’s brewing company, making regular business trips across Europe. As he travelled, he made time for hunting and natural history, steadily amassing a collection of “birds and beasts”.

In 1881, Chapman turned his sights northwards to Spitzbergen, a cluster of islands situated between Norway and the North Pole. (The islands were later renamed the Svalbard Archipelago.) They supported no permanent settlements, but were exploited by whalers and served as a focal point of Arctic exploration.

For the Victorians, the Arctic was a frontier of scientific discovery, natural history, and intrepid adventure. At the time of Chapman’s journey, John Franklin’s ill-fated 1845 expedition was still fresh in the public imagination. Franklin had set out to chart the Northwest Passage, but his ships became icebound; all 129 crewmen perished, and later searches revealed they had resorted to cannibalism in a bid to survive.

Given the dangers that lay ahead, it is little wonder that Chapman experienced great difficulty in “securing a mere handful of men” for his expedition. But on the 12th of July 1881, with his crew assembled, Chapman set sail from North Shields harbour.

Unlike Parry’s north-western exploration, Chapman followed the better-known Northeast Passage along the coasts of Europe and Russia. The crew were joined in Norway by their ice navigator, Capt. Carlsen of St. Olaf, before pressing ahead to Spitzbergen.

“The grim grandeur of hopeless desolation will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it. The day was foggy, and dense masses of grey mist appeared to fill each valley, obscuring and encircling the mountain slopes. Above the clouds, the sharp and lofty peaks stood out in bold jagged contour against the sky.”

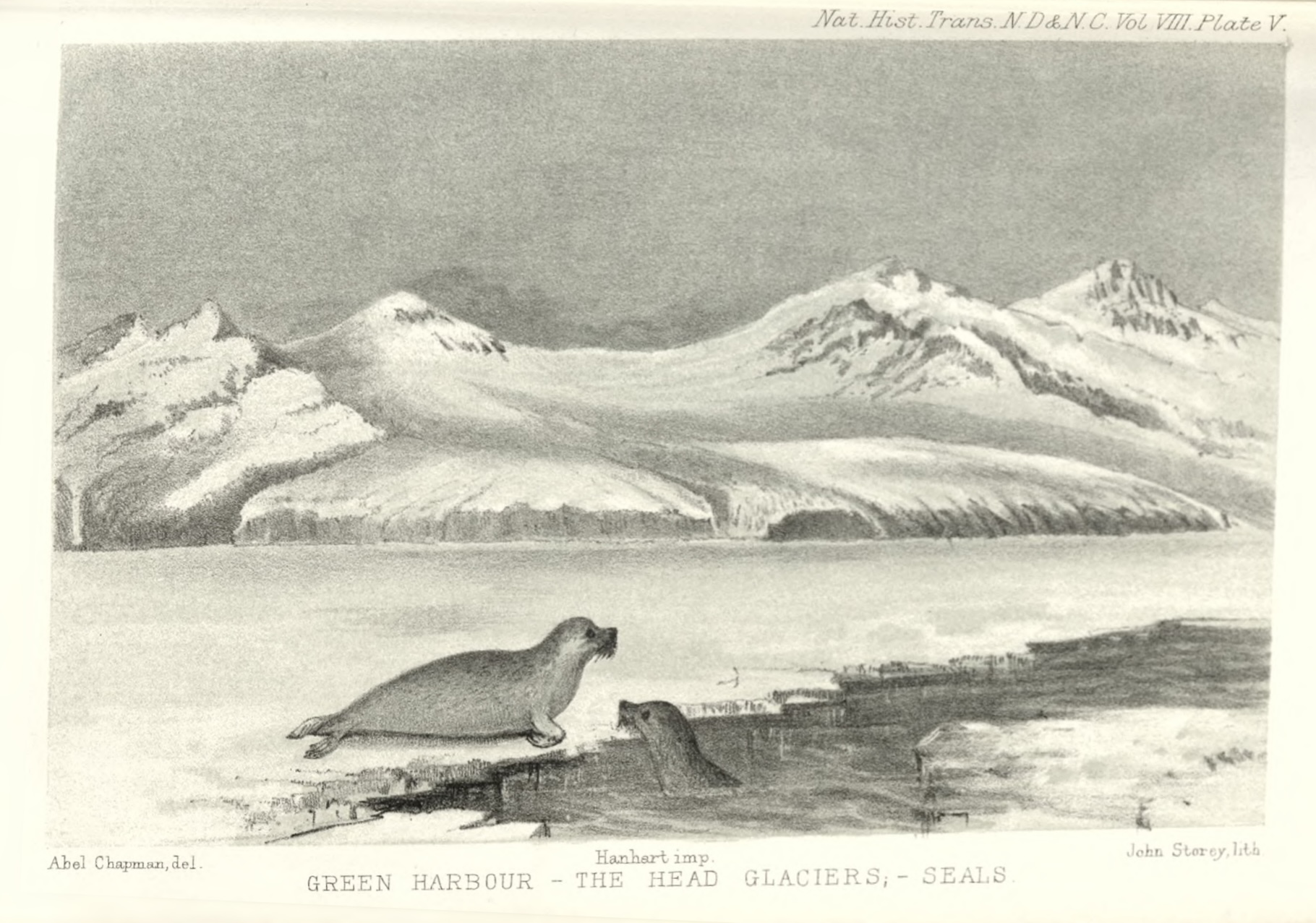

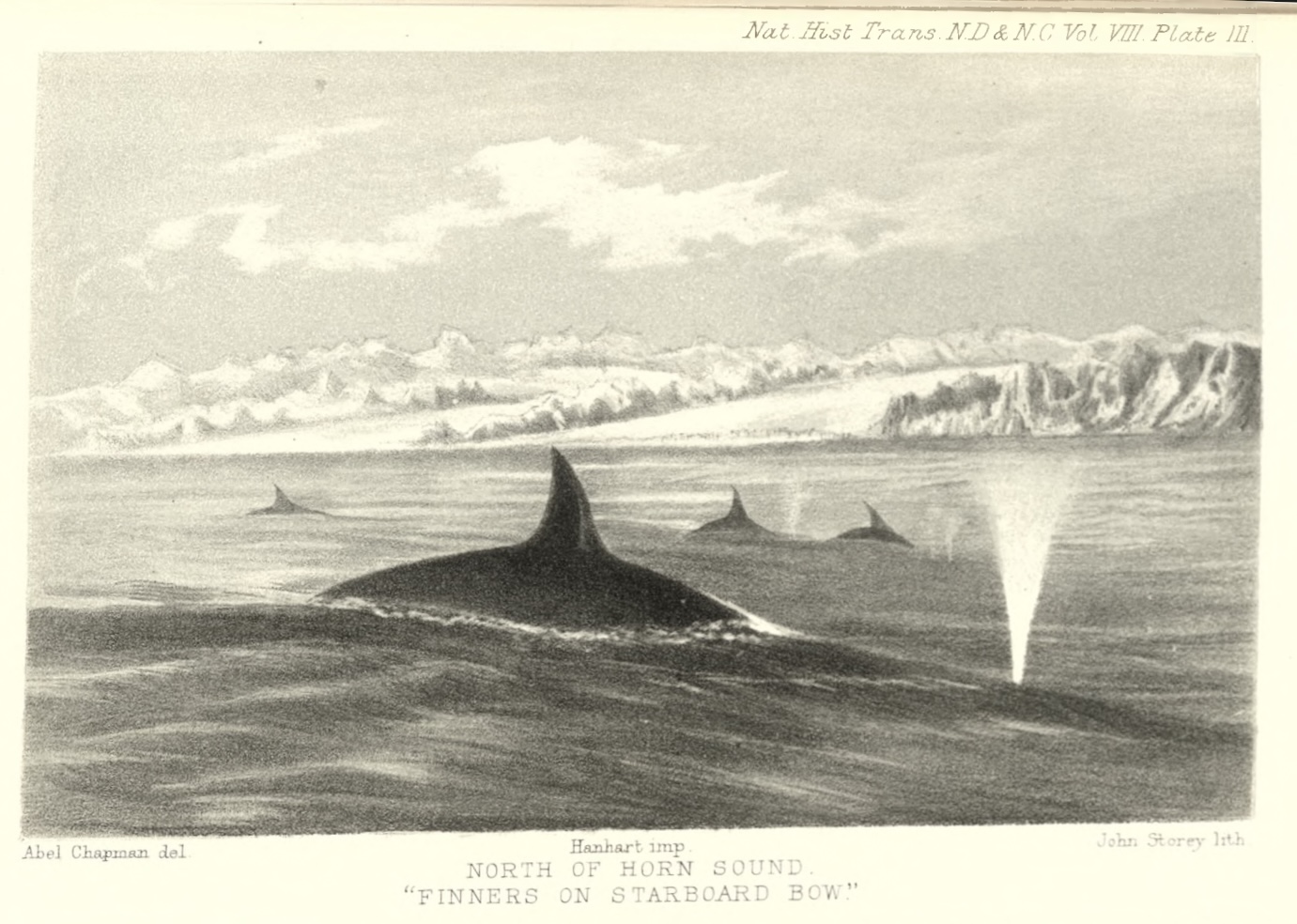

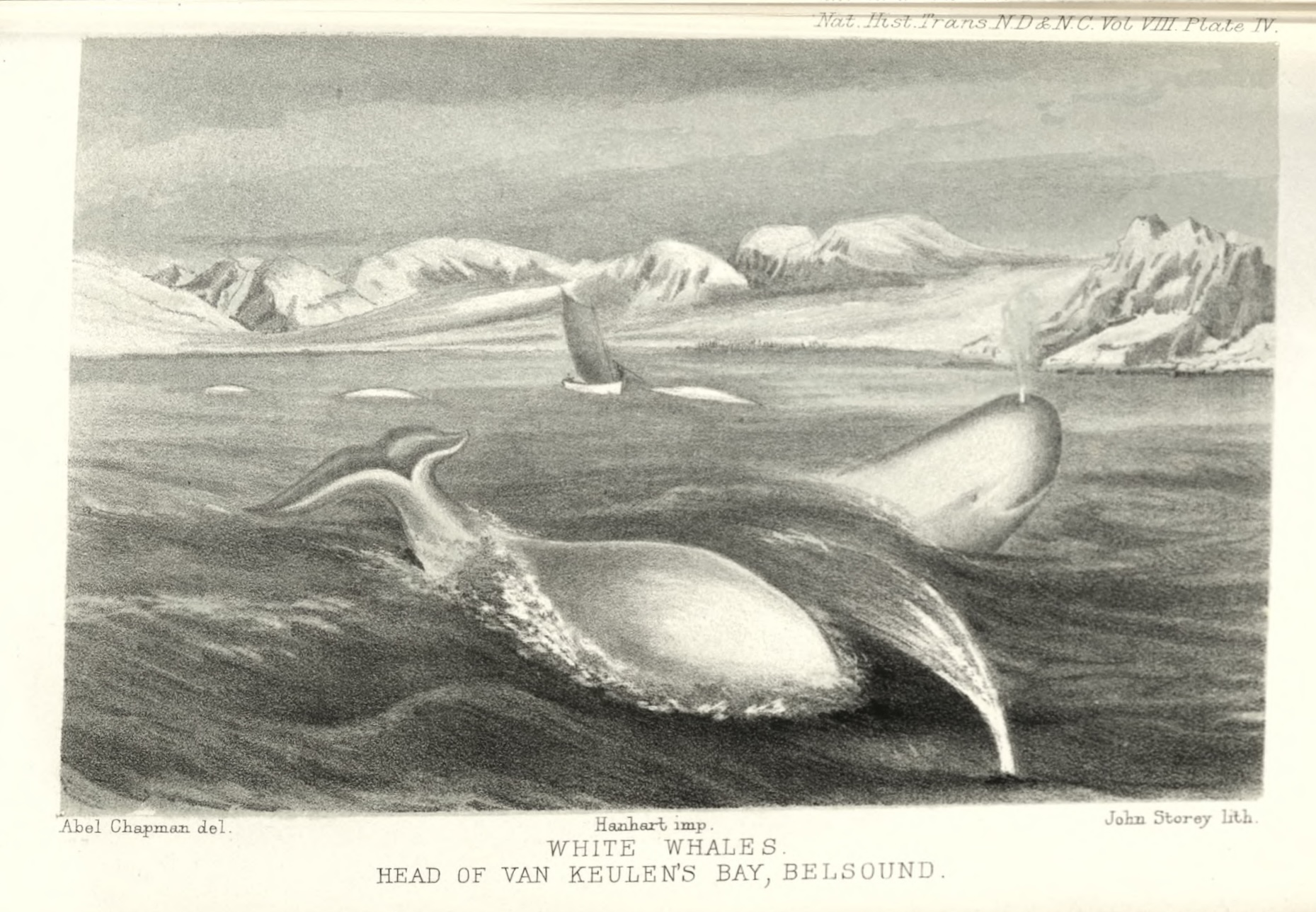

In the weeks that followed, the crew skirted the Spitzbergen coast, landing where conditions allowed. Glaciers rose 300 feet above sea level, and Chapman’s men rescued the crew of a whaling schooner trapped in the ice. Although the sun dipped at midnight, there was no darkness. Petrels and kittiwakes made “wild, Babel-like cries” whilst colossal whales, stretching 80 feet long, surfaced near the ship.

On land, it was all too easy to become disoriented as the unusually clear atmosphere made the fjords seem narrower and the mountains appear closer than they really were. Danger was never far away; on one expedition Chapman “came across the remains of a rude wooden coffin, half buried in big stones. The place had evidently been explored by polar bears, and all that remained of the poor whaler were a few buttons”.

Although much of the land was snow-clad and barren, the men happened across valleys and pastures where reindeer grazed among saxifrages, yellow poppies and purple valerian. They hunted the deer for meat, along with seals and seabirds.

Chapman’s meticulous accounts of hunting are punctuated by finely observed descriptions of his prey. He possessed a genuine concern for wildlife alongside his passion for the chase; a seemingly contradictory outlook typical of the hunter-naturalists of his time. He condemned overhunting and the “wanton and indiscriminate persecution” that drove walruses from Western Spitzbergen, whilst admiring a Norwegian cargo of polar bears and white whales.

On departing Spitzbergen, the crew encountered packed ice and dense fog. Landfall was finally made at the Norwegian shipping town of Hammerfest, which marked the start of a smooth passage home. The ship arrived at the River Tyne on the 22nd of August 1881, six weeks after setting sail.

Hunter-naturalist Chapman went on to travel extensively across Africa and Europe, collecting trophy heads whilst also working to protect the Spanish ibex and to establish the Sabi Game Reserve in South Africa. Upon his death, many of his trophies were donated to the Hancock Museum. Dan Gordon, Keeper of Biology, has explored the ethical complexities of Chapman’s colonial-era collection in his blog Behind the Heads.

Chapman published an account of his ‘Journey to Spitzbergen’ in the1880–1881 Transactions, along with his catalogue of Spitzbergen ornithology. A curious postscript offers a hint of hubris alongside an uncanny foreshadowing of arctic tourism; Chapman dismisses later ornithologists as contributing little beyond his own observations of Spitzbergen, and laments “those cosmopolitan stragglers which sooner or later turn up everywhere”.