Ian Bower revisits a landmark book in the history of nature writing

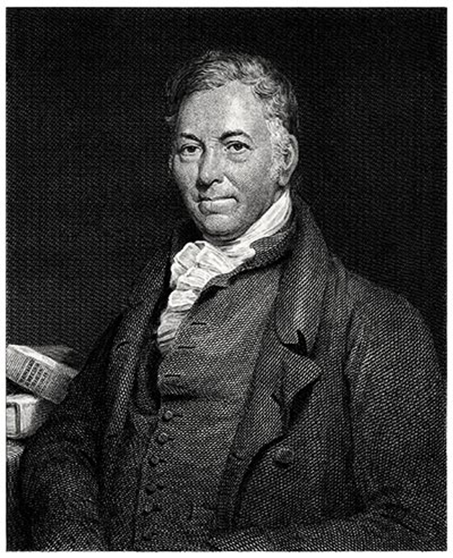

In my recent blog I considered the life and work of Gilbert White and his hugely influential eighteenth-century work, The Natural History of Selborne. This was a seminal publication in the development of natural history writing, which continues to resonate in the twenty-first century. A close contemporary of White’s, who was to have a similarly significant impact in this field, was Thomas Bewick, a native of Northumberland who had strong links to the NHSN. Both men were to produce iconic works that still richly inform and reward anyone with an interest in the natural world.

Thomas Bewick was born on either 10 or 12 August 1753 at the family small holding in Cherryburn in the Tyne valley. His rural childhood with its close connection to the local landscape provided him with a lifelong interest in the natural world. In his Memoir, Bewick wrote: “from the little window at my bed-head I noticed all the varying seasons of the year, and when the Spring put in, I felt charmed with the music of birds which strained their little throats to proclaim it.”

Bewick developed a keen interest in representing the abundance of nature that surrounded him by becoming a skilled and enthusiastic self-taught artist. From an early age he would produce drawings and sketches on every available surface, ranging from the blank margins in schoolbooks to local gravestones. As he became older his observations of animals and birds became more complex and detailed as he attempted to represent as closely as possible the creatures he encountered. This approach was in tune with the emerging spirit of the age. During the 1750s all kinds of people across the nation, including Gilbert White, were closely observing nature and recording their findings in the form of journals and diaries. Their relationship with the natural world was becoming more informed, passionate and nuanced and Bewick was also deeply informed and influenced by these creative ambitions.

In 1767 Bewick was apprenticed to Ralph Beilby, a jobbing engraver in Newcastle upon Tyne, whose multi-faceted business incorporated occasional orders for crude wood blocks. The vogue for cheaply produced children’s books illustrated by woodcuts enabled Bewick to hone his skills as a wood engraver. From his earliest days with Beilby, Bewick used boxwood for his illustrations. Being close-grained and hard this type of wood enabled him to produce small blocks seldom exceeding 2.5 x 5cm. The delicate linear and tonal effects that this medium allowed him to skilfully create elevated the use of wood engraving for book illustration to an unprecedented artistic level.

Several of the books that Bewick worked on during this period incorporated illustrations of animals and he was able to bring the creatures to animated life. In A Pretty Book of Pictures for Little Masters (1779) he rendered images of lions, jackals and porcupines set against a realistic background that captured a vibrant and striking sense of their individual characters.

Because of his awareness of the limitations and inaccuracies of the existing range of illustrated books on animals, Bewick began to consider the possibility of producing a new publication. This would be aimed at the emerging audience who were developing a keen interest in the natural world. He had positive discussions with Beilby about this ambition, and was also encouraged by a Mr Solomon Hodgson, the then editor of the Newcastle Chronicle. Beilby offered to write the text that would accompany Bewick’s illustrations. The idea was to create a work that was informed by earlier publications on animals by illustrious authors such as the Comte de Buffon and Thomas Pennant but intended to be more accessible, attractive and affordable to a contemporary readership. Bewick undertook extensive research into the subject by reading widely, and this included Gilbert White’s recently published book. In his Memoir Bewick writes “I was much pleased with White’s History of Selborne”

In this way, the slow process of producing what would become the History of Quadrupeds was instigated.

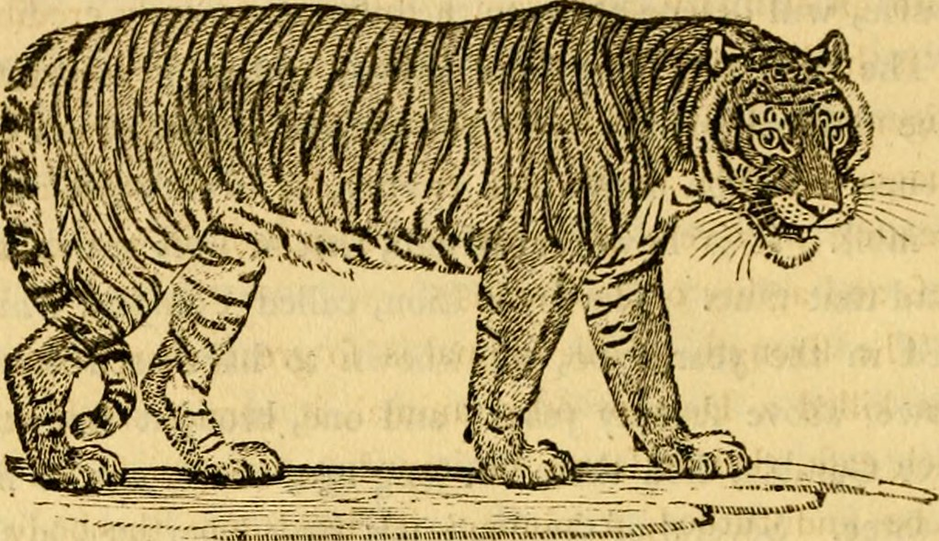

One of the issues confronting Bewick was how he could produce images of the animals that were as accurate and representative as possible. Working during the evenings, at the end of the working day, Bewick’s most successful engravings were those where he was able to view and sketch the living creature. Examples of this include his famous representation of the Chillingham Bull, which he was able to sketch from life by visiting the Northumberland parkland in which its herd was located, and where they still live today. The travelling menageries which visited the local area during this period also enabled him to render impressive and life-like images of the tiger and the baboon.

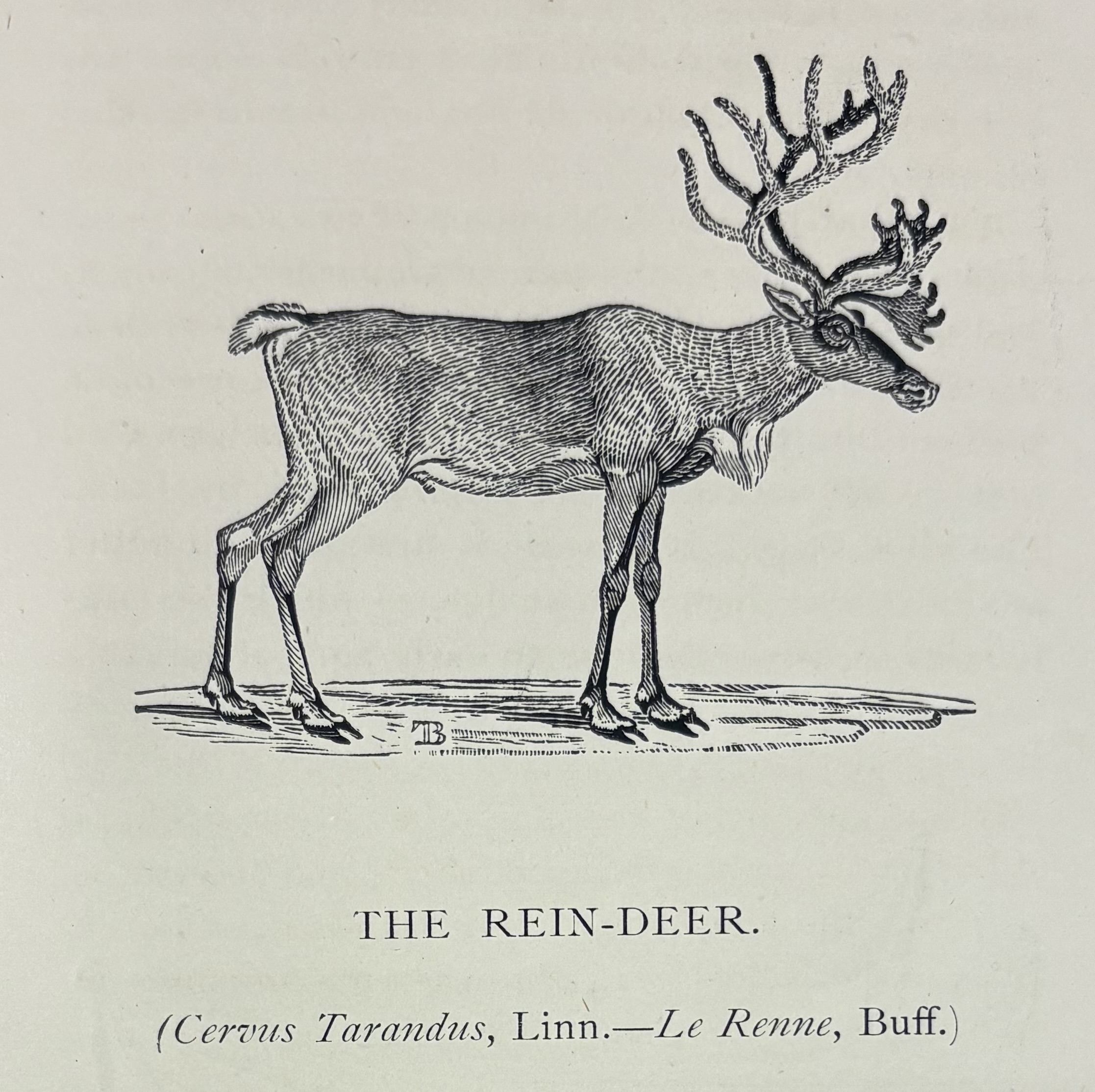

He was also able to access a living reindeer which belonged to a local collector.

On a more domestic scale, because of his relatively easy access to live animals, his images of various breeds of horses and dogs and his notably impressive mole were all beautifully captured.

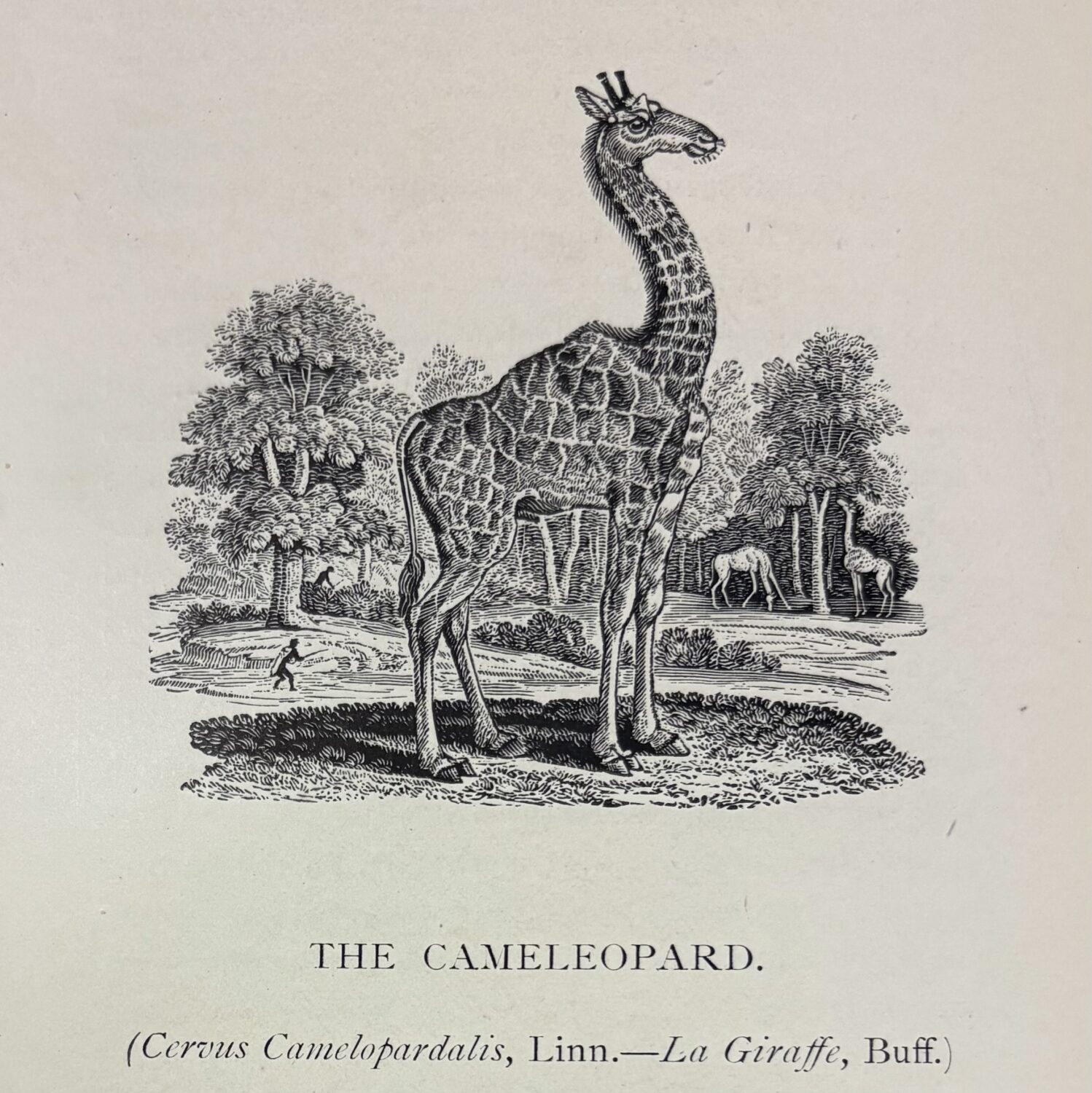

The images contained within the book were unavoidably of varying quality because of Bewick’s difficulty of gaining access to intimate examples of some of the creatures incorporated in it. The least successful of these include the giraffe, which was largely fanciful. Overall, though, the book was highly successful in marrying engaging images with entertaining and idiosyncratic text which combined to provide a fresh and informative perspective on the natural world.

The first readers of Quadrupeds were particularly struck by the fact that the animals being portrayed were often in realistic locations such as fields, farmyards, forests and hills. Another innovative component was the inclusion of anecdotal vignettes, or tail-pieces as they became known. These images were located at the end of the short descriptive essays on the animals and provided entertaining and informative images of contemporary country life as observed by Bewick, often with a wryly humorous tone. The combination of images, text and vignettes provided a unique and winning formula, engaging readers in a novel and immersive way. The first edition of Quadrupeds contained 200 figures and 103 tail-pieces. One illustrative example of a tail-piece portrays an elderly countryman precariously carrying his wife across a stream. The wife is carrying a basket on her head and a baby on her back. In the air above them a V formation of geese is flying by.

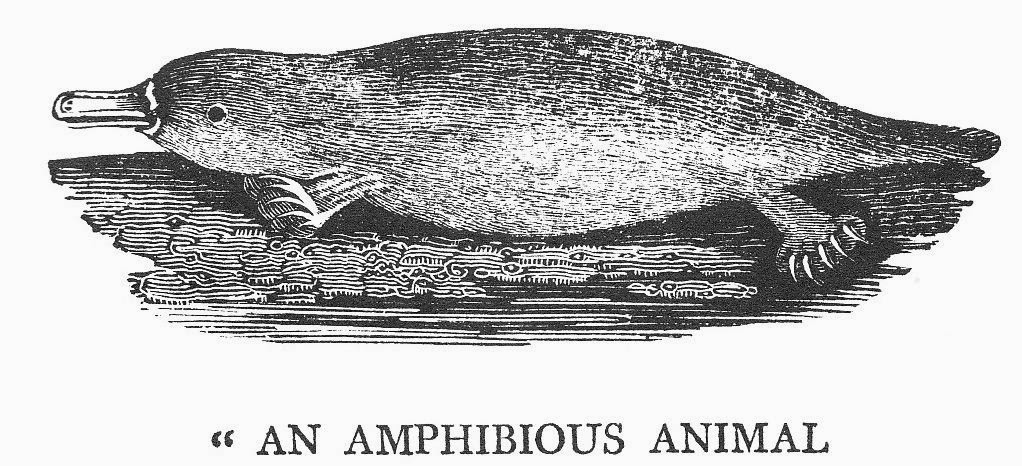

The first edition of A General History of Quadrupeds was published in 1790 and was an immediate and sustained success. The book sold 1600 copies in its year of issue and the subsequent second edition of 1800 copies in 1791 was also a sell-out. The book delighted its readership with its simple format of an illustrated book, with an index at the front where an animal such as the mole, which they were familiar with, was sandwiched between exotic sounding creatures such as the Mexican Hog and the Monax, a rabbit like marmot from North America. The NHSN library collection at Great North Museum: Hancock contains copies of all the editions of Quadrupeds published within Bewick’s lifetime. Also available in the North East Nature Archive are some of Bewick’s original sketches for the book. Subsequent editions of Quadrupeds remained fresh and vital by incorporating an array of new creatures. The fourth edition which was published in 1800 included additional entries on new livestock breeds but more importantly also featured two newly discovered and unusual Australian animals, a wombat and a platypus. In the book the as yet unnamed platypus was titled simply ‘An Amphibious Animal’. These creatures had been sent to Newcastle in 1798 by John Hunter, the governor of New South Wales. Bewick was able to draw the preserved specimens when they arrived at the Literary and Philosophical Society in the City and was one of the first naturalists to publish illustrations of these fascinating new creatures.

Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne had been published in 1789, so within a year two landmark publications with a focus on British natural history had appeared and were greeted with tremendous acclaim. Bewick’s Quadrupeds and Selborne’s book both provided contemporary readers with a fresh, engaging and entertaining way to appreciate and understand the natural world. Both books were imbued with the authors deeply personal and individual relationship with nature. They also provided tangible evidence of the divide that was beginning to emerge between specialized and expensive works intended for the professional scientists, and more affordable and accessible works for amateur enthusiasts of nature of both sexes.

Many of the subsequent Victorian editions of White’s book incorporated illustrations inspired by or even copied from Bewick’s works, in many cases designed or engraved by his former apprentices. In this way an unexpected posthumous partnership was established between the two men, who never encountered each other during their lifetimes.

The next and perhaps most significant publication that Bewick was to work on was the first volume of his History of British Birds, which was devoted to ‘Land Birds’; Volume Two would focus on ‘Water Birds’. This book was published in 1797 and succeeded in establishing a new benchmark of excellence, greatly surpassing anything that he had previously achieved. An appreciation of this book will be the subject of my next blog.

If you would like to view any of the Bewick works discussed in this blog then it is possible to do so by contacting the library at Great North Museum: Hancock. The email address is library@greatnorthmuseum.org.uk.