Heritage Researcher Mel Tuckett opens up the NHSN’s Transactions and discovers the early origins of its community

On becoming a volunteer ranger with NHSN back in 2022, I was inspired by its aim of being a welcoming community. Everyone was keen to open up the Society and spread opportunities to enjoy the natural world. When I became a volunteer in the North East Nature Archive (NENA) in 2023 I began exploring the Transactions of the Society, looking to trace how this community started to form. Searching through our Transactions I discovered that although it began as an elite study group set up by wealthy men of science, the NHSN gradually welcomed working people, women, children and people with disabilities to become the diverse society we enjoy today.

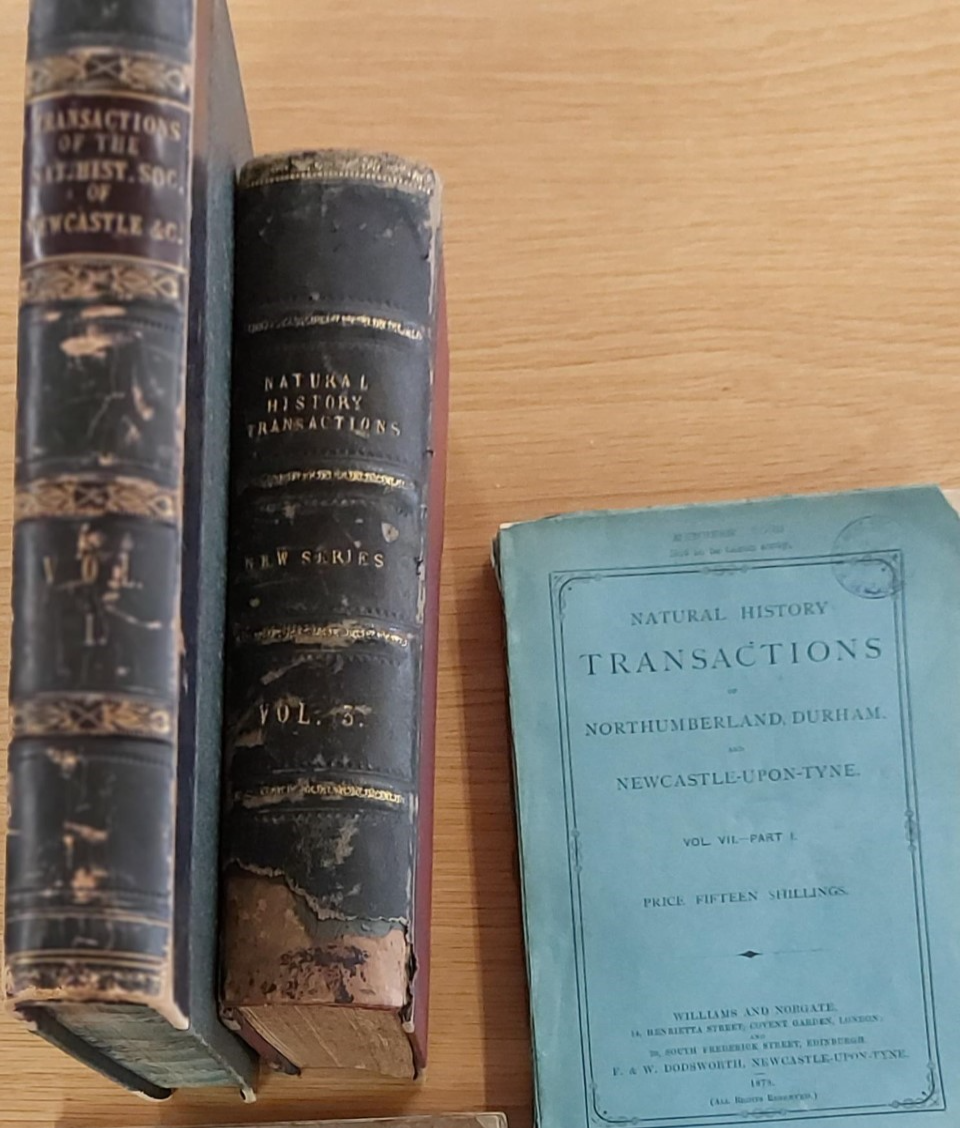

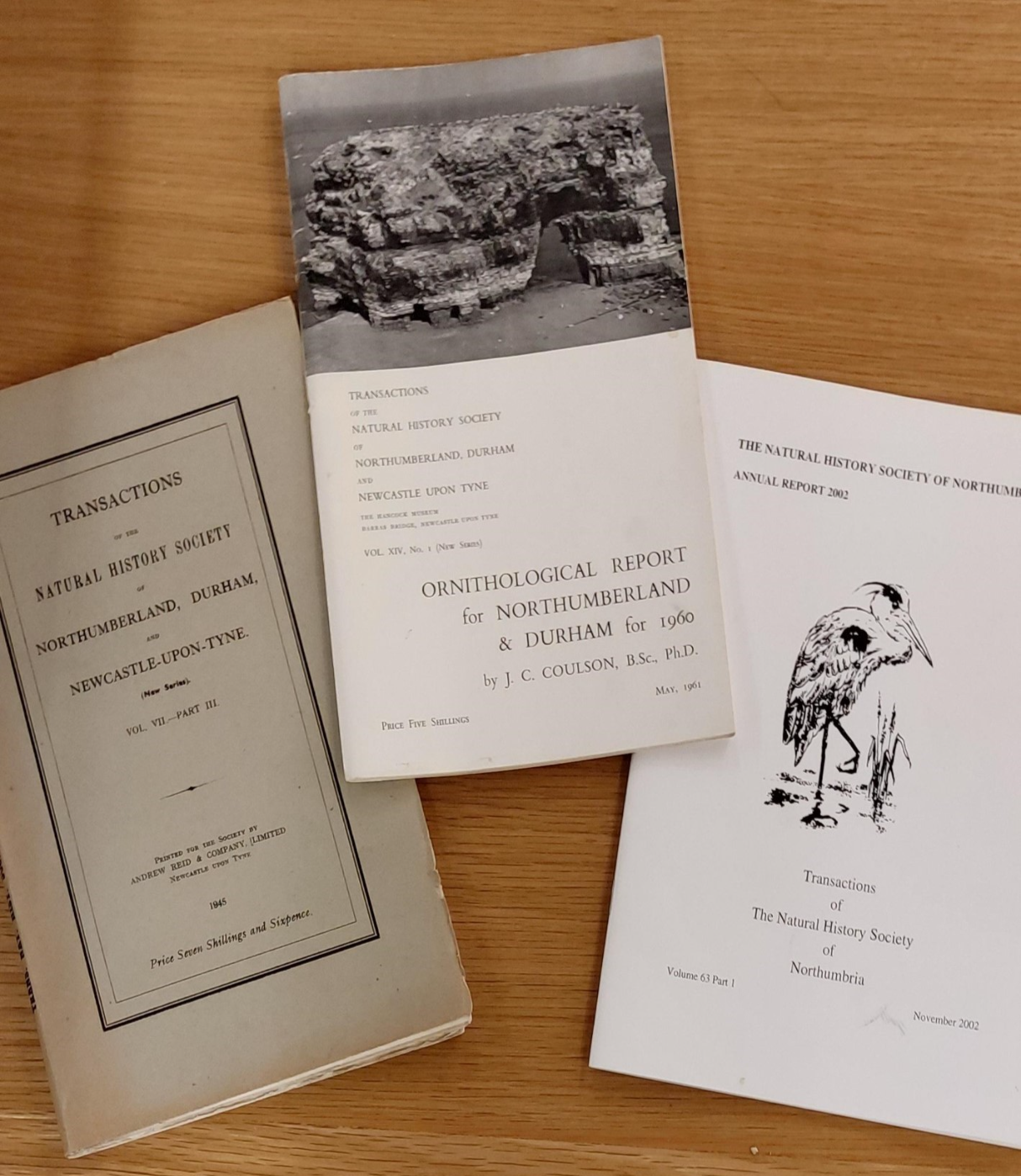

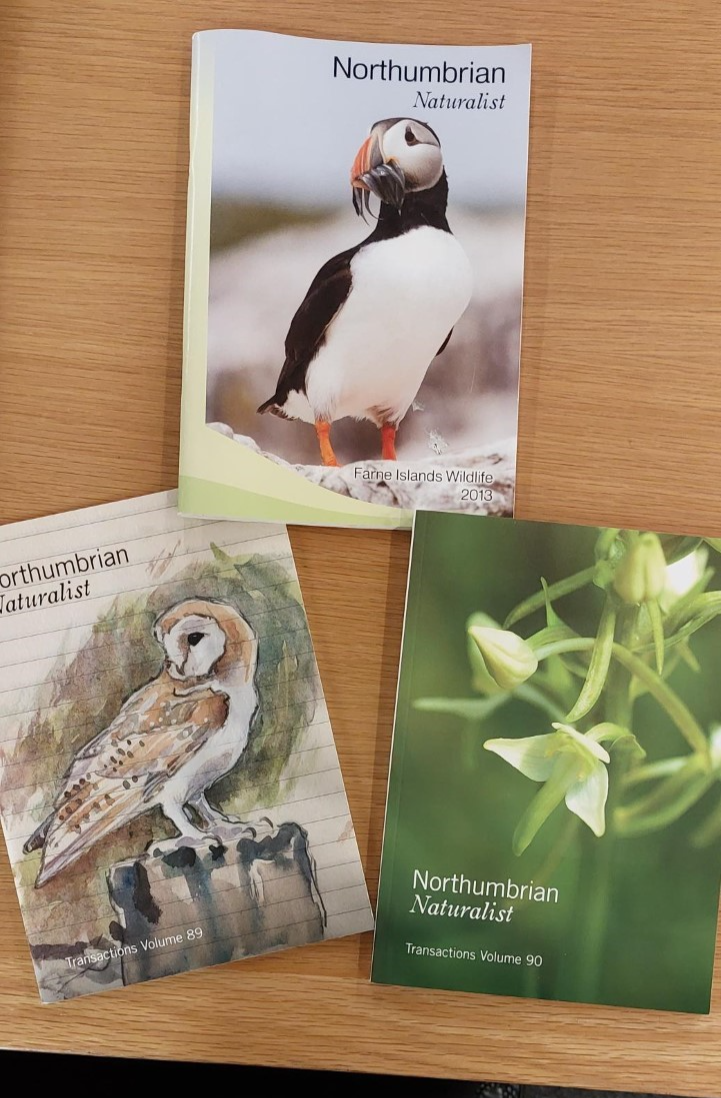

The Transactions are a series of books which document the activities and history of NHSN. They contain scientific papers, annual reports, minutes of meetings and lists of members. Here’s what they’ve looked like through the ages.

.

Working with the Transactions requires a bit of attention, as they have a complex numbering and naming system. They don’t correspond to one year each, and often overlap in time periods. There are also several series beginning in 1830, just after the Natural History Society began in 1829. There were two initial volumes.

In 1846, an offshoot of the main society, the Tyneside Field Naturalists’ Club (TFNC) started to publish its own Transactions which ran to six volumes up until 1864. In 1865, the two groups combined their publications into what became known as the first or Old Series, comprising fourteen volumes. In 1901 the second or New Series began, and continues to run up to the present day. We are now on volume 95.

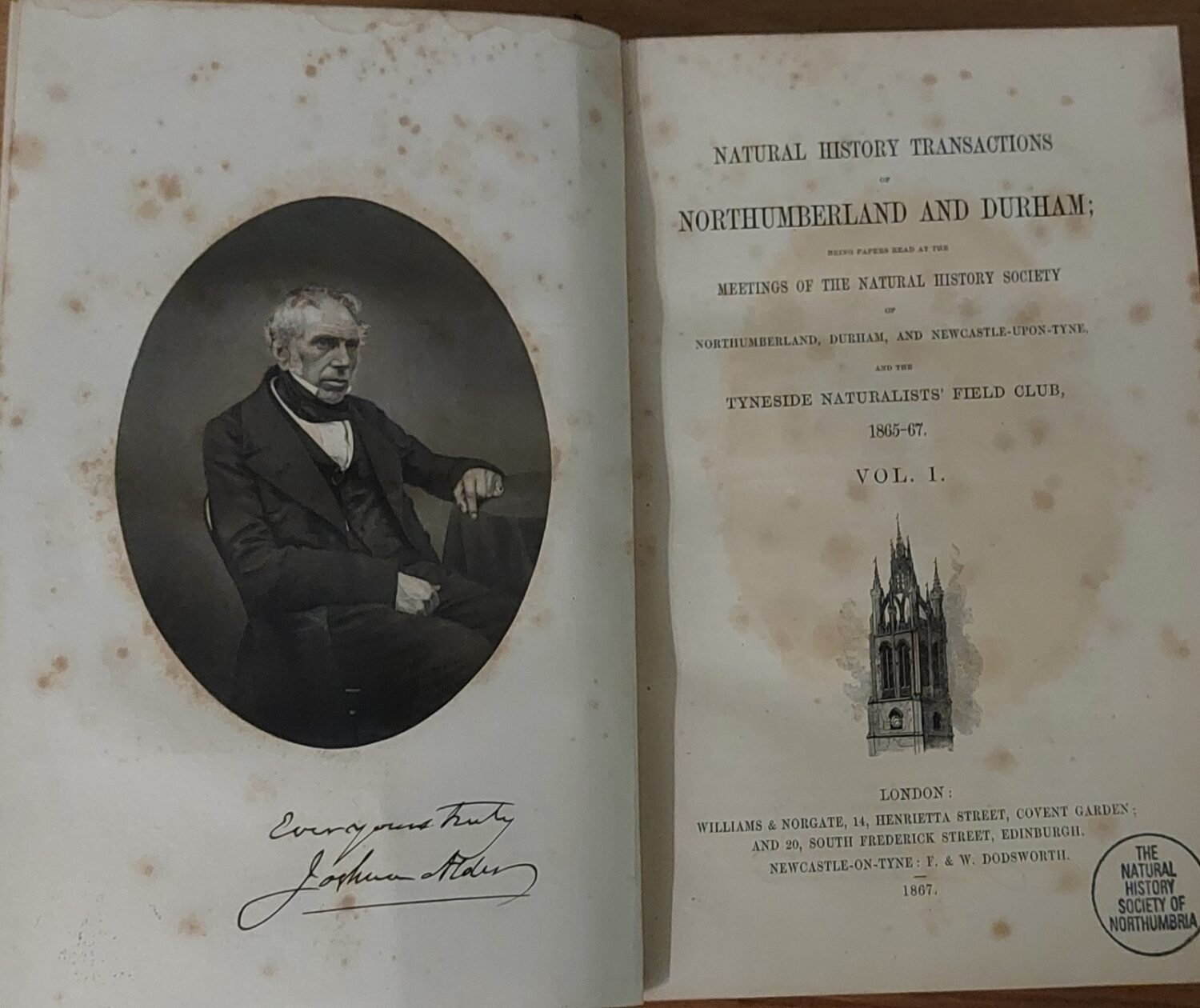

I began my exploration of the NHSN community by going back to the earliest volume. It outlines how much of an elite group it was, run by and for men from professional and upper-class backgrounds. It was comprised of clergymen such as the Reverends R.H. Brandling and W. Turner, and politicians such as the Rt. Hon. Lord Ravensworth and Matthew Bell M.P. There were plenty of aristocrats, such as Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan of Wallington Hall, a Duke of Northumberland, and a Marquess of Londonderry. And not forgetting pillars of the establishment such as a Lord Bishop of Durham, and a Mayor of Newcastle. These men identified themselves as “[p]ersons either scientifically or economically interested in the Pursuit of Natural History” and saw that the establishment of a society could “tend much to the Advancement of that Study”. Their approach focused on sharing discoveries, discussing theories and collecting and exchanging specimens.

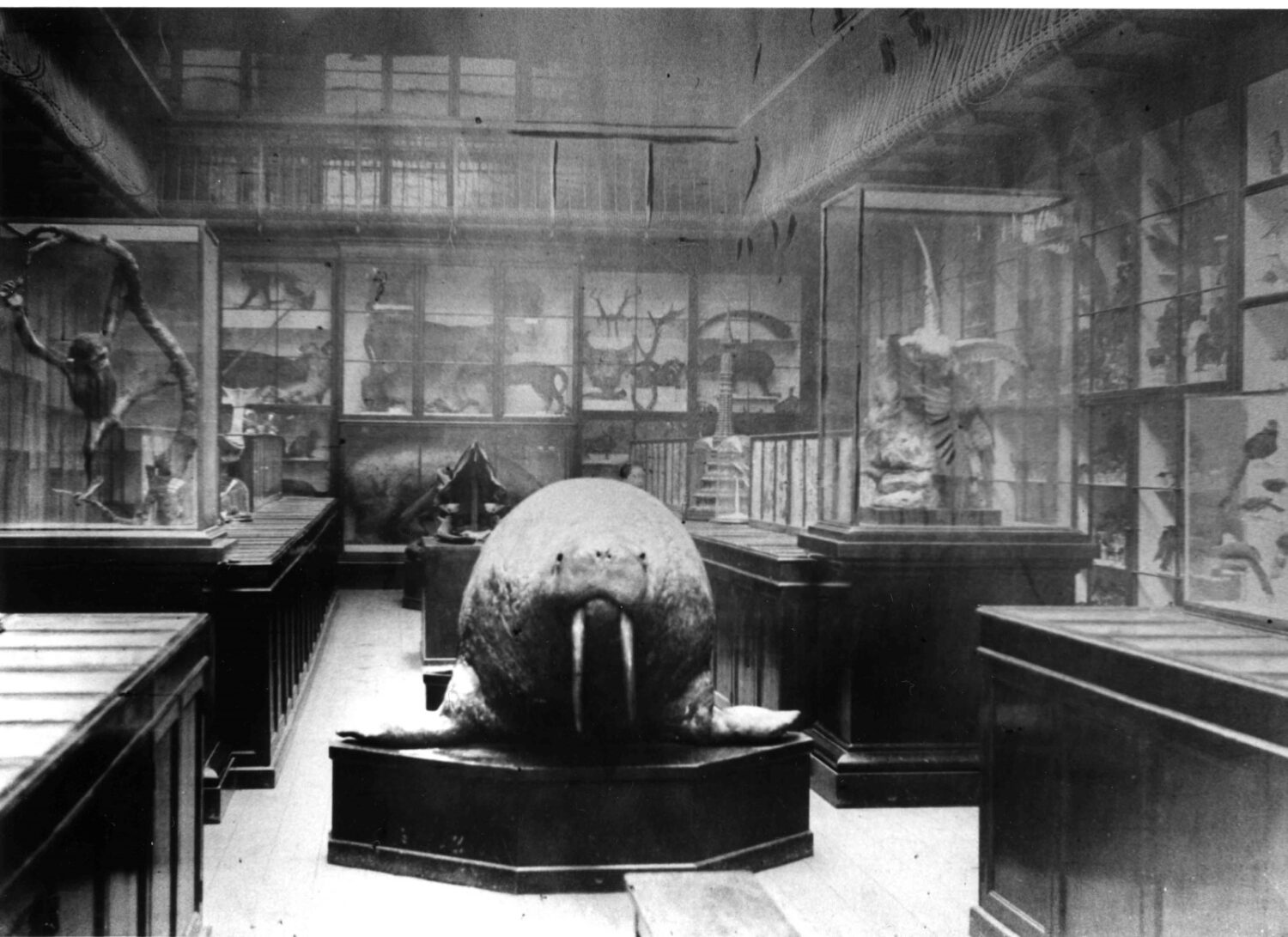

The establishment of the Society at this time was part of a wider scientific movement shaped by the work of such men as Carl Linneus (1707-1778). The key task in natural science was to map, classify and name the natural world, feeding a desire to categorise, collect and in effect control nature. The main method of study was to kill, dissect and preserve. The collection now housed at the Great North Museum; Hancock began as a record of these methods and was initially housed at a building attached to Newcastle’s Literary and Philosophical Society.

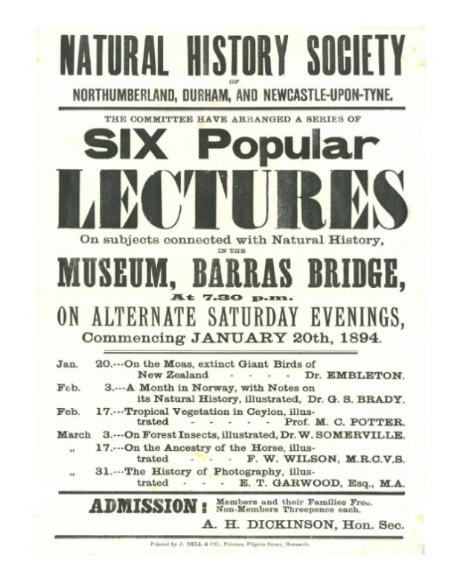

Yet as early as 1831, the Society understood that it should work towards “lifting the veil” that hid scientific knowledge from its widest audience. President Joshua Alder stated that the Society must reach out to “scientific strangers” to expand the understanding of nature. Free or low-priced access to the Museum was established, and lectures were put on to enable working people to expand their knowledge of the natural world.

Gradually the society’s reach began to expand to men from working backgrounds. Thomas Bold (1817-1874) was a good example of this changing landscape. Employed as a grocer and seedsman in Newcastle’s Bigg Market, Bold became well respected for his skill and knowledge in entomology, corresponding with leading scientists and becoming an authority on beetles.

The path to recognising women as scientific strangers within the NHSN community was a more complex and incremental process. In 1847, women were permitted to become members, but this was only in an honorary capacity and only if they could be said to be distinguished by their “attainments in the study of Natural History.” This was hard to achieve at this time, as women’s roles were mostly in the home and educational opportunities were very limited. It was only very wealthy women who could join this community, and Lord Armstrong’s wife Lady Margaret seems to have been the first woman to be accepted into this circle. The earliest Transactions do not list the names of ordinary members, but in 1867 Volume 2 of the first series notes that amongst the 134 such members there were ten women, six of whom appear to have been married to NHSN members – with only one unmarried woman listed, a Miss Bates.

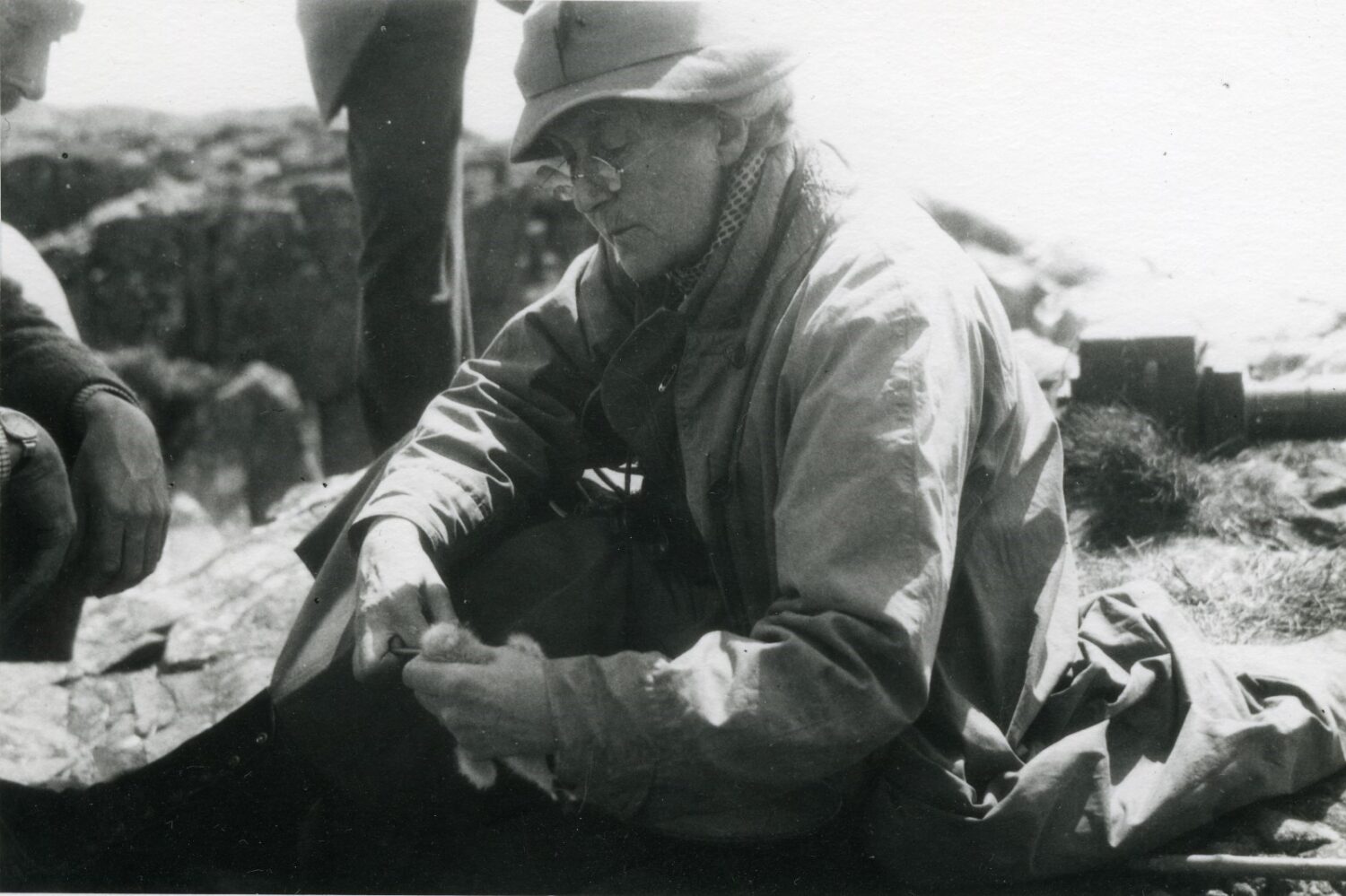

However, a change in the ethos of natural science worked to help women, and also less wealthy people, to become more integral within the field and thus within the Society. Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and others began a new scientific approach which depended upon carrying out work in the field. It was argued that observing plants and animals in their natural habitats and interacting with each other was a key method for understanding the complex development of the natural world. Darwin felt that these relationships were the drivers of the process of evolution and needed to be better understood. This was a key driver for the setting up of the Tyneside Naturalist Field Club and it organised ‘hands on’ field trips with a strong social element such as meals at nearby public houses. As a result, a wider cross section of members was able to pursue this more participatory approach. Eventually, this opened up greater opportunities for women who began to get more actively involved when accompanying their husbands and fathers on field trips. The opportunity of becoming a full member took a while longer to be taken up by women and in 1871, Volume 4 of the TFNC Transactions, the President George Stewardson–Brady laments that their club had no women members. He hopes that more women would join for their own benefit and that of the Club. Interestingly he seeks to strengthen his argument by suggesting that women could enhance their role as mothers by gaining knowledge of the natural world which they could pass on to their children. Volume 7 of the TFNC Transactions notes that by 1877 five women had joined and although they continued to be in a small minority, numbers gradually increased.

Women’s influence within the Society gradually evolved as the new century began. Their early roles were those thought suitable for women such as with working with shells and flowers. Volume 1 of the New Series outlines that the first female employee was Miss T. Conradi, who began in 1904 and was given the work of remounting and re-labelling the shell collection. However, the same volume makes clear that as early as 1905, a significant leap forward was made for women’s influence in NHSN. The prestigious Evening Talk was presented by two women, Dr Ethel Williams who chaired the presentation, and Miss E. Hollis who gave a talk entitled ‘The Northumbrian Coast.’ Women were now moving out of traditional helper roles and into the prestigious leading roles of science and authority. This was however, a slow process into positions of governance. It was not until 1937 that the ornithologist Catharine Hodgkin was elected as the first woman on the Society’s Council.

The inclusion of children and young people into the NHSN community was, like the lecture series, an early policy to the expand the reach of the society and disseminate its knowledge. As early as 1836, a programme of educational opportunities was established. Charity schools were invited to the Museum and school visits have been encouraged since this time. Saturday morning talks began: as Volume 10 of the New Series reveals, 900 children attended the first one in 1888. In 1902, a series of Christmas lectures took place with the use of the ‘magic lantern.’ This was an early type of slide projector in which images were placed on glass and lit from behind. These talks were the inspiration for the Society’s Lantern Fund, which continues into the present day and works to provide children with chances to access nature.

Yet Volume 13 documents the Society’s most innovative early policy, which reached out to people with disabilities. In 1897, the House Governor at the Royal Victoria School for the Blind was given “a small collection of duplicate Birds and two or three Quadrupeds” to use with his students. The aim was to enable them to touch and experience the form of nature in ways not available elsewhere. Here NHSN was trying to pull back the veil which excluded some of society’s most marginalised young people in a way which seems to still resonate today.

The Transactions have proved to be a key source of information and inspiration for the work I carry out today. I am now proud to be employed as a member of the NHSN Nature’s Cure team where I work to welcome everyone into the natural history community. Our team provides this welcome through greater access to the North East Nature Archive, putting on events and collecting and preserving local peoples’ stories of connection with nature. There is much work still to be done, and we hope for example to reach out more widely to people from all ethnicities. The work of including everybody is always ongoing. As recognised by Society President Rev. J.E. Leefe in 1875, “Nature is so vast a domain that there is open to everyone a field of independent study, rich in results, and inviting us everywhere to enter and enjoy.”