Digitization volunteer Sandra Bishop explores a fascinating insight into climate, disease and ecology in the early Transactions of the NHSN

When I heard the NHSN was seeking volunteers to digitise the Society’s Transactions dating back to 1831, I leapt at the chance. Open access to knowledge and nature matters to me, and helping make natural history archives freely available online has been a real privilege.

At first, I wasn’t sure what to expect or—to be honest—what the Transactions were. The answer is pretty straightforward; Transactions was the original name of the NHSN journal (it was renamed North East Naturalist in 2010). The first volume I uploaded, 1851–54, had me hooked.

Two things took me by surprise. First, the volume offers a remarkable window into both nineteenth-century natural history and the broader world of mid-Victorian society. Second, I was struck by the sheer dedication of some of the natural historians of that era.

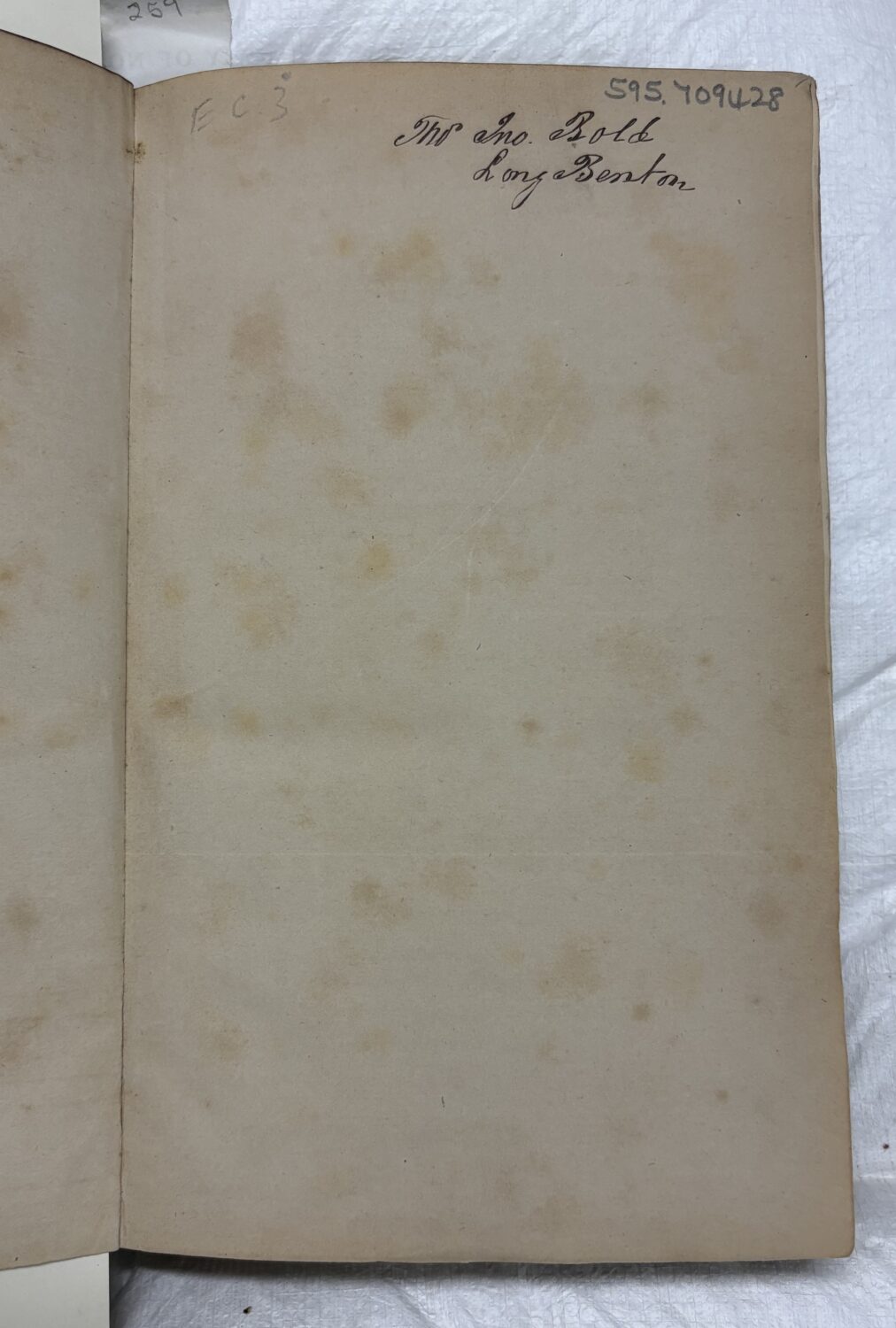

Take, for example, the esteemed entomologist Thomas John Bold (1816–74). Bold was born in Tanfield Lea in Durham. His family moved to Newbottle when he was a child, before later settling in Longbenton. At school, Bold developed a keen interest in natural history, a passion he carried throughout his life. He was one of the original members of the Tyneside Naturalists’ Field Club and, whilst earning his living as a grocer, he established himself as a respected entomologist.

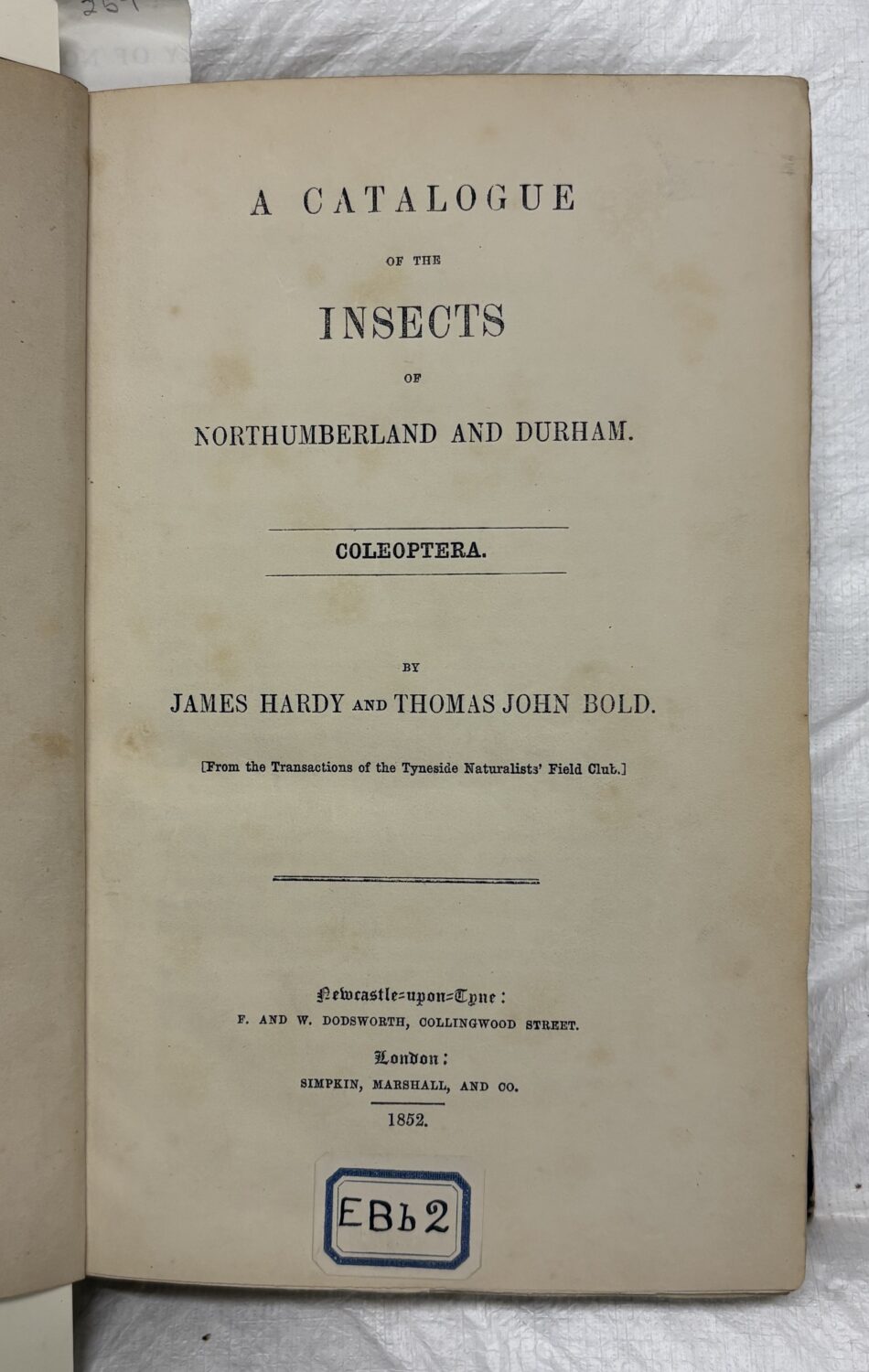

Along with fellow entomologist James Hardy, Bold co-authored an extensive work titled A Catalogue of the Insects of Northumberland and Durham. Just imagine the level of commitment required from these two men as they painstakingly collected and documented their specimens!

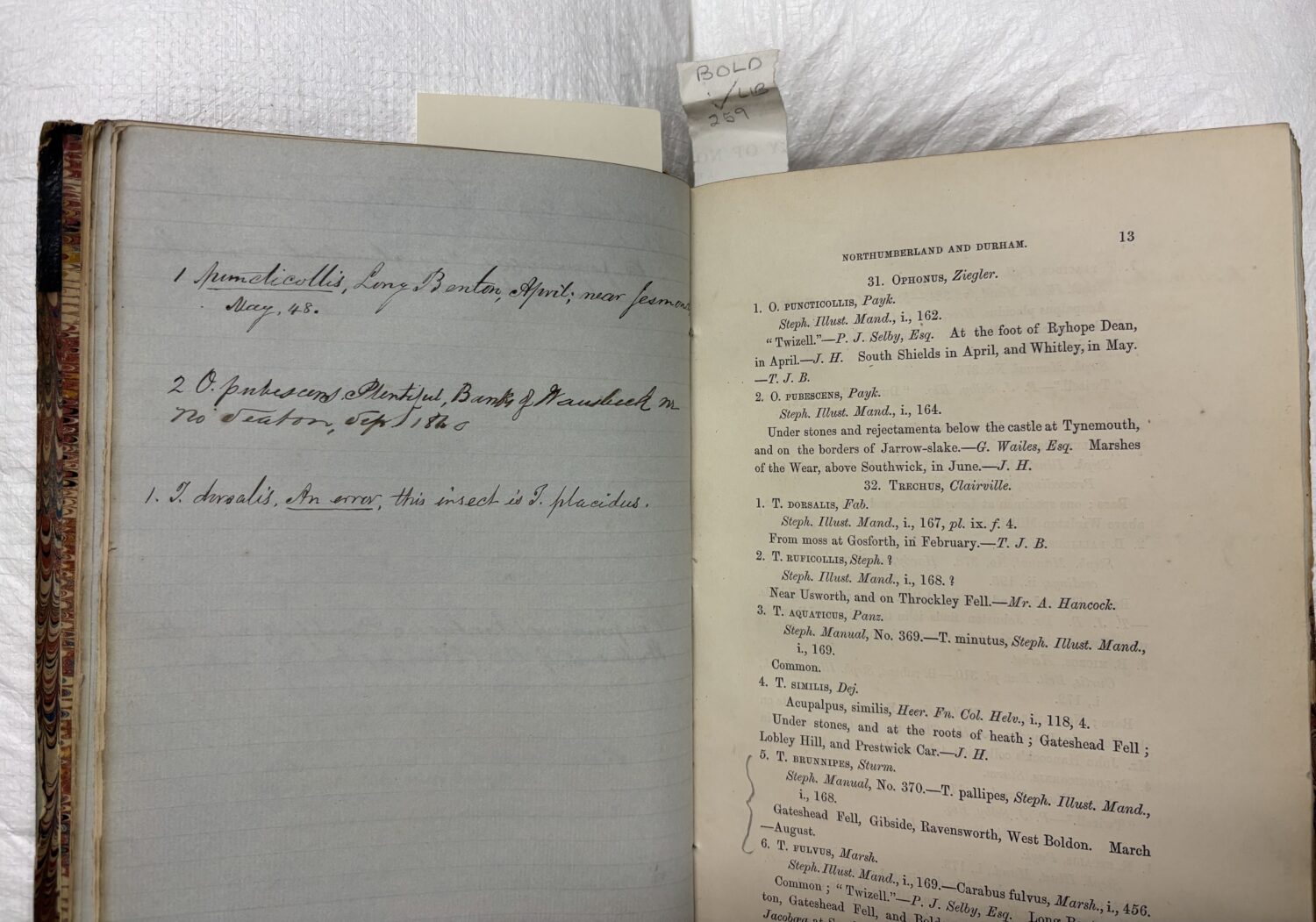

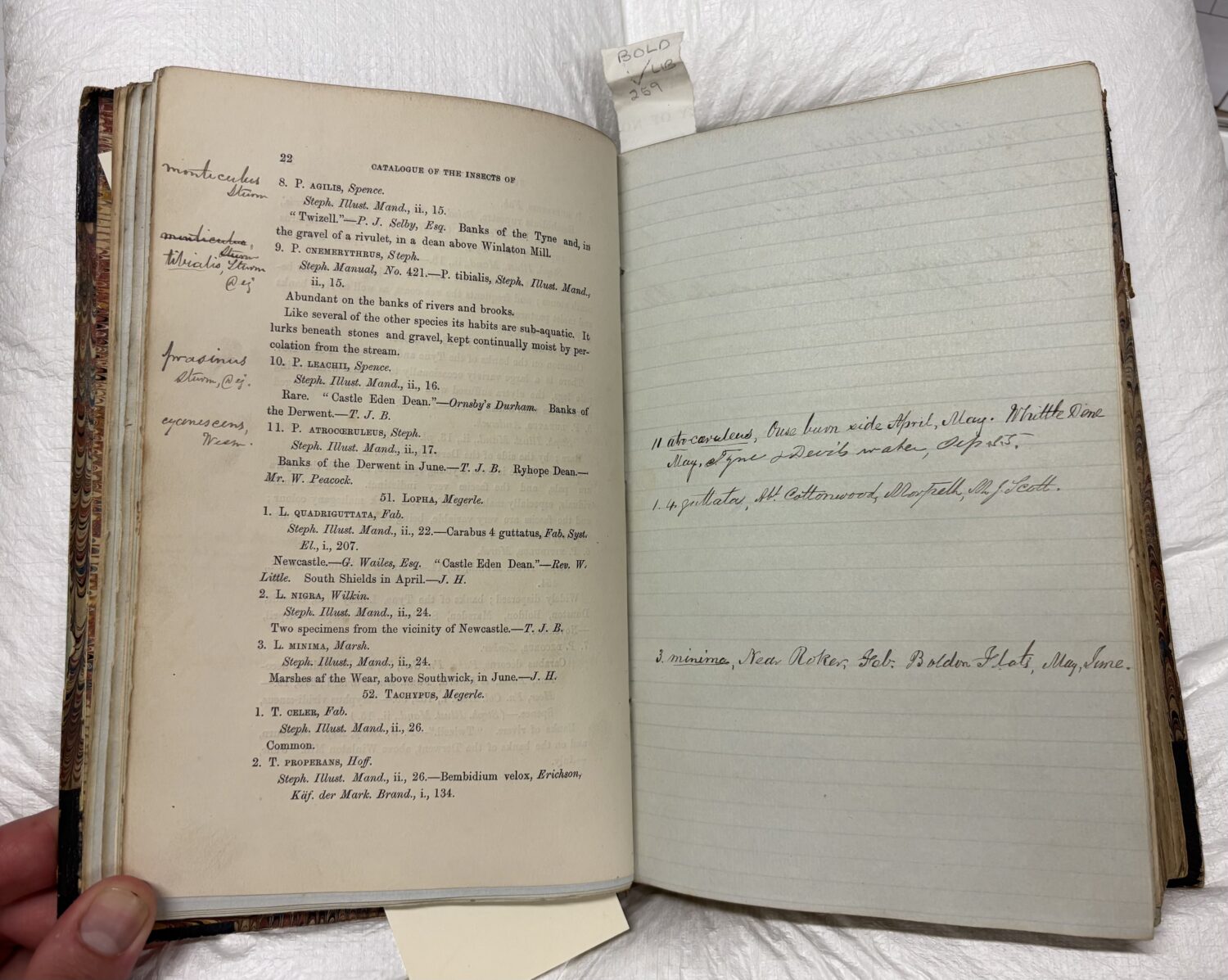

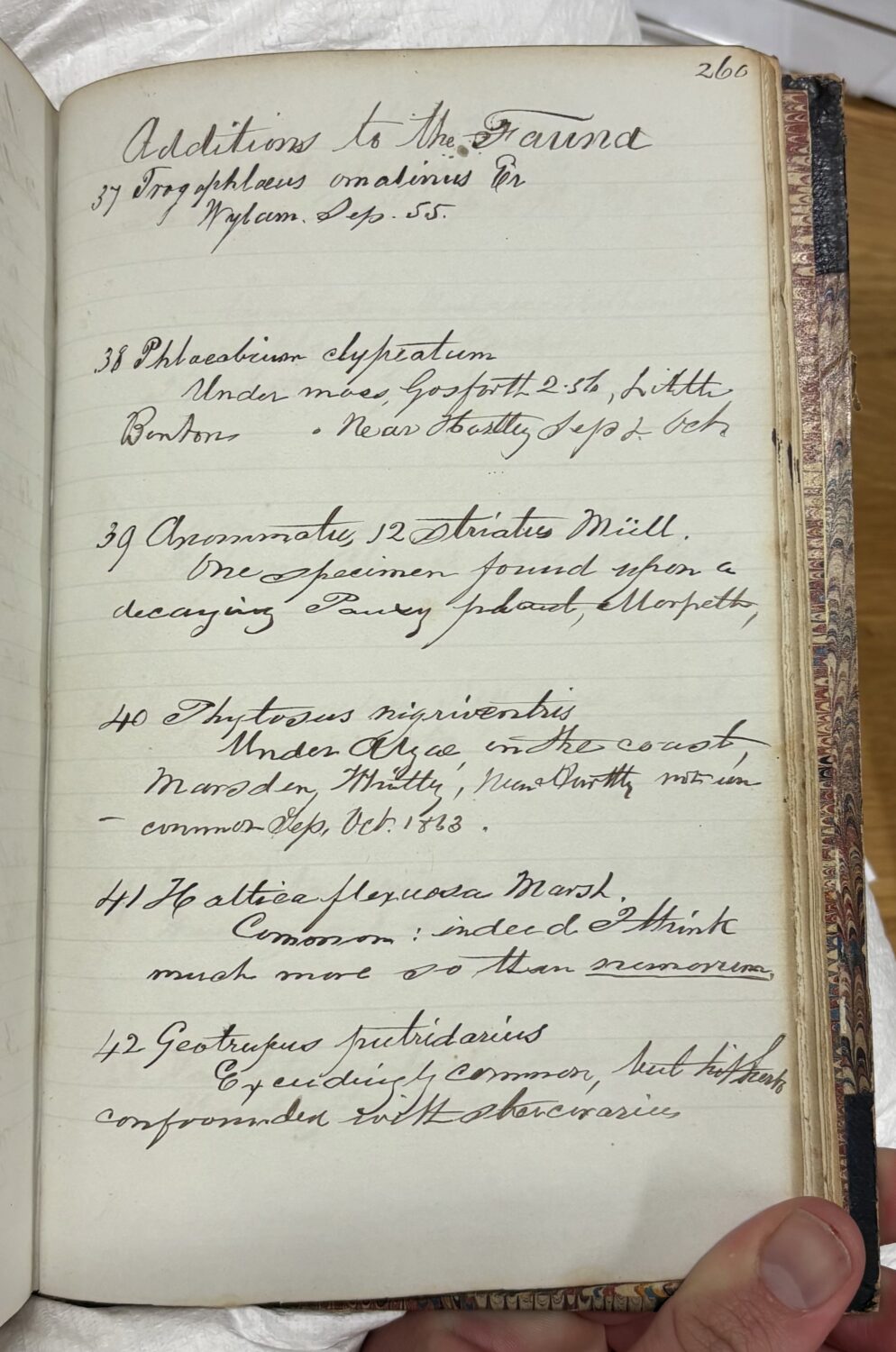

A copy of the Catalogue can be found in the NHSN archives. Like most catalogues that have been part of personal libraries, it was bound interleaved with notepaper and used as a spotting catalogue. Some of the handwritten observations were likely made by Bold himself, with a new ‘additions’ section at the back in manuscript.

According to Joseph Wright, whose memoir of Bold can be found in the 1880–89 Transactions,

In 1870, nearly twenty-five years after the publication of the catalogue, [Bold] presented to the Club a revision of it. During the period which had elapsed, the number of species found in the district had increased by a third, necessitating a review of what had previously been done. This laborious revision, which led to the new edition of the Catalogue, was entirely the work of Mr Bold, and it met with a most favourable reception from the leading entomologists of the day.

The Catalogue is undoubtedly a remarkable achievement. However, it was one of Bold’s shorter essays that really caught my attention.

In 1853, Bold presented his paper ‘Notes on the Effects of the Extreme Wet Winter of 1852–53’ to the Tyneside Naturalists’ Field Club. The winter had proven to be the perfect opportunity for Bold to test, through meticulous observation, the hypothesis that “extreme wet is more prejudicial to insect life than severe cold.”

He noted a marked scarcity of beetles that overwintered as underground larvae, and a reduction in those that lived on or near the ground. He lamented the impact of reduced insect numbers on his fellow entomologists; such poor conditions severely limited collecting. However, some insects—such as aphids—increased in number. And this is where things get really interesting!

Bold writes about “swarms”, “multitudes”, “masses” and “plagues of flies” that “filled both eyes and mouth”. He describes “buildings speckled by corpses” and crops that looked as though they were “saturated by bloody rain”.

This language is surprisingly gothic in an otherwise factual account in a natural history journal. It is a reminder of the Victorian fascination for the macabre and the sensational. In an era where penny dreadfuls were a common form of entertainment and the Victorian press favoured sensationalist stories, perhaps even rational natural historians were not entirely immune to the allure of the gothic!

Bold observes that the swarms of aphids appeared at the time of a cholera outbreak (a concerning number of outbreaks occurred in Newcastle and Gateshead between 1839–53). Just four years earlier, in 1849, the London physician John Snow had published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, identifying the disease as water-borne. However, according to Bold, there was uncertainty in the minds of many people as to how the disease was transmitted. Consequently, the aphids “caused a great deal of unnecessary alarm” as people feared that they were the source of the outbreak, and they became known as ‘cholera flies’. It must have been terrifying to watch the swarms descend!

It is precisely this sort of detail, hidden among the early Transactions, that fascinates me most. They show the very real interactions of humans with the natural world, and our changing relationships with nature and science.

For anyone keen to learn more about Thomas John Bold and Victorian entomology, Bold’s collections of insects are housed at Great North Museum: Hancock.

The articles discussed here can be found in the following Transactions volumes online:

- Transactions of The Tyneside Naturalists’ Field Club, 1851 – 54

- Notes on the Effects of the Extreme Wet Winter of 1852 – 53, on Insects, by Thomas John Bold (pp. 338 – 342)

- A Catalogue of the Insects of Northumberland and Durham (Part ii), by James Hardy, and Thomas John Bold (pp. 21 – 97)

- A Catalogue of the Insects of Northumberland and Durham (Part iii.) by James Hardy, and Thomas John Bold (pp. 164 – 287)

- Natural History Transactions of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1880 – 89

- Memoir of the late Thomas J. Bold. By Joseph Wright (pp. 33 – 39)