NHSN library and archive volunteer Julia Black explores the life and legacy of the Hancock Museum’s very own condor

While preparing the Summary for one of the recently digitised NHSN Transactions, I was startled to read the following from 1902: “It is also a matter of interest to record the laying of an egg by the Condor in the grounds of the Museum on the 10th of April last…”

At first I thought it might be an April Fool, but as the date of the meeting was May, it seemed unlikely. I quickly put a message onto the Archive Volunteers WhatsApp group to see if anyone had ever heard of there being a live Condor at the Museum, and to my amazement, I found out that this was indeed true!

The donation to the Society of a nine-month-old Andean Condor nestling (Vultur gryphus) from Corral Quimado, in the province of Coquimbo, Chile by Mr W.C. Tripler of Santiago, was recorded in the List of Donations at the end of the Report of the Natural History Society Committee for 1878-1887. The donation is also recorded in the Committee Meeting of 2nd June 1886, with the comment that “it was agreed that a specimen of Tungstate of Iron (Wolfram) be presented to W.C. Tripler Esq.” We believe Mr W.C. Tripler is Mr William Creighton Tripler, born in 1822 in New York City, who worked as merchant in Chile and lived in Santiago until his death in 1897. While there is no mention of how the Condor travelled here, four years later the same Mr Tripler donated a living ‘Huanaco’ (now known as a guanaco, a camelid closely related to the llama) from Chile. The guanaco was brought to Middlesbrough by steamer, so it seems likely the Condor arrived in the same way.

There is nothing in the Transactions to record how or where the young condor was cared for until 1889, when the report of the Annual Meeting for 1888-1889 notes that a subscription had raised £21 8 0 for “a large Aviary or Cage for the Condor”. The aviary was erected at the back of the Museum, and many visitors came to see the condor. John Hancock’s suggestion to put some jesses on her and put her on a block outside the Museum was obviously not taken up.

In the Presidential Address to Members of the Tyneside Naturalists’ Field Club on 15 May 1889, Mr John Philipson wrote: “To those who desire a lesson in the keeping and management of wild beasts, I would recommend a visit to the Museum, where Mr Wright (the Museum Keeper) will show them the Condor presented by Dr Pattinson, apparently happy in its confinement, and watching the movement of visitors”.

In an even more unlikely twist to this tale, it seems that Tripler donated a second condor in November 1888 as a companion to the first bird. Mr Philipson’s address went on: “The obliging keeper will also tell them how another Condor, given by Mr Tripler, appreciated the gentle nursing it received during an illness, which unfortunately proved fatal”. The bird had sadly died in March 1889. The donation of the skeleton of this bird to the Society in April 1890 was recorded in the List of Donations at the end of the Report of the Natural History Society Committee from 30th June 1889 to 30th June 1890. The skeleton featured in the ‘Bones – Skeleton Secrets of the Animal World’ exhibition at the North East Museum – Hancock in 2017.

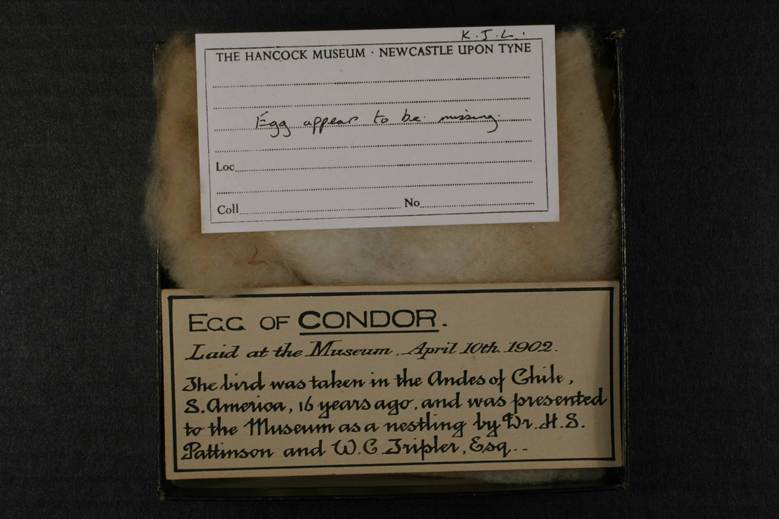

There is then very little about the condor in the Society’s records, until 1902, when the newly/appointed curator E. Leonard Gill records his diary “the laying by the Museum Condor of her first egg at the considerable age of nearly 17 years”. By the following Monday, he had photographed the egg and placed it on display in the Museum. The egg was described as being 4 ½ by 2 ½ inches, pure white without markings, with a very rough surface, and the shell light and thin. We still have the box in which it was kept, although the egg itself appears to be missing.

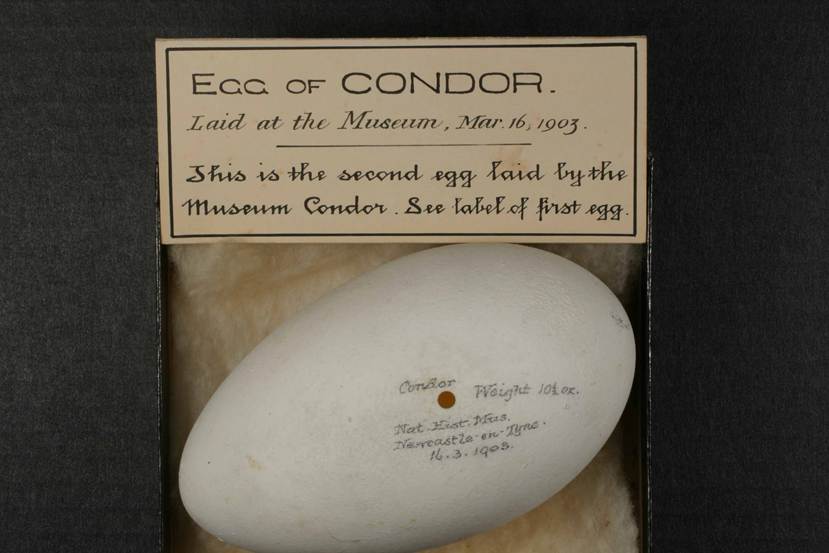

Gill wrote that the Condor laid another egg in his Curator’s Report of 8th April 1903, and that it was placed side by side with the first egg in the Museum. This egg we do still have!

In 1904 Gill wrote an article for the Transactions about the Condor’s sense of smell. He described how when dissecting a rabbit in his room at the back of the Museum, which had an open window about 10 yards from the condor’s cage, she took no notice when he was removing the brain, but as soon as he opened the abdominal cavity – allowing the “characteristic but by no means powerful”’ odour of warm viscera to escape – she became intensely excited. She ran to and fro, repeatedly stretching her neck through the bars towards the window, and then executed a series of vigorous flights across the cage from one of the perching stumps to another. She continued to show signs of excitement for half an hour or so, until Gill shut the window and left the building. Experiments by others had demonstrated that the Condor had no serviceable sense of smell; Gill believed otherwise.

The condor continued to lay a single egg every succeeding spring until 1908, when she laid two eggs. “Evidently pleased with this double performance”, the Newcastle Journal noted, “she gave up the laying business in 1909, but resumed laying in spring 1910 when she was in her twenty-fifth year”.

The regional press, in fact, seemed to take a particular interest in the Museum’s famous condor. In 1910, in an article headed ‘The Highest Flier’ the Journal encouraged its readers to “see the Condor and her eggs, taking their children with them”. But it seems the Condor could be really disagreeable; in 1909, Gill had prepared a caution notice to be placed on the cage, discouraging children from placing their fingers through the bars.

On Saturday 15April 1911, the Condor laid her last egg. Gill’s diary records: “Condor laid an egg but she smashed it”. This probably reflected the bird’s declining health: she was in heavy moult and obviously very ill. She died not long afterward, on 16 June. Notices of her death appeared in the Chronicle and the North Mail the latter, written by Gill, amounts to an obituary for this famous bird:

“‘The condor which probably thousands of visitors to the Hancock Museum, Newcastle, have stared and wondered at, is dead. From far Corral Quimado in Chili, the condor hailed in 1886, and she has lived an unruffled life in Newcastle ever since. She was only a nestling when Dr H. Salvin Pattinson and Mr W C Tripler presented her to the museum. Gradually she developed into a fine adult female, and except when emerging from her bath – one of course is not expected to call on a condor even at such time – she was always to be seen in splendid feather and condition. The condor’s behaviour was generally exemplary. She had her moods, and she could really be disagreeable; but although in coming to maturity she developed a decidedly unfriendly disposition, she remained, singularly enough, on affectionate terms with the late Mr William Dinning, formerly secretary of the Natural History Society. The only other person she would tolerate for a moment inside her cage was the museum caretaker, Mr William Voult.

Of the vulture the average man has rather a disagreeable idea. He thinks of whitening corpses on sandy plains, the prey of the bloodthirsty giant of the air. It is not a pleasant notion. Still the condor, which is not only the largest of the American vultures, but the largest of all birds of prey, is a magnificent creature, to whose splendid soaring flights the pen of Darwin could do but justice.”

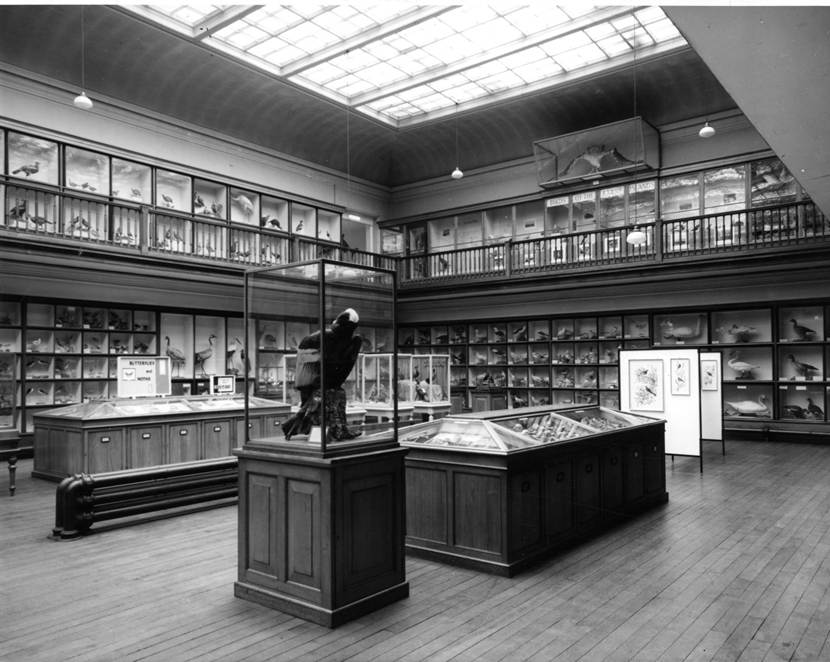

Since the condor was dead, the logical next thing to do was to stuff her and put her in the Museum. Gill’s curator’s report from 1911 takes up the story:

“[T]he moult had not gone so far as to spoil her plumage altogether, and we have been able to make quite a good job of skinning and setting her up. The attitude we have put her in is the one I have always thought to be her best. It is the attitude she habitually sat in on the roof of her house when she had not been disturbed for some time by seeing strangers; at such times she used to draw her wings well round her and draw up her neck ruff round the back of her head, and then, seen from behind and with her head turned over her shoulder, she had much of the appearance and dignity of an eagle.”

For many years, the condor was displayed in the entrance hall to the Museum, until in 1927 she was cleaned and photographed by the new curator, T. Russell Goddard, and placed in the Bird Room.

Today she sits in a case high up in Great North Museum: Hancock’s impressive wall of taxidermy, in the company of a Desert Wheatear, a Pallas’s Sandgrouse, a Turkey Vulture, a Dorcas Gazelle and a Desert Kangaroo Rat. A wonderful reminder of the truly remarkable story of the Geordie Condor.

Acknowledgments

Enormous thanks to former archivist June Holmes and freelance researcher Anthony Flowers for access to their excellent reports and for answering additional questions, and to Sarah Seeley, Mel Tuckett and Maureen Flisher for assistance with further research. Finally, a big thank you to Pete Mitchell for coining the term ‘the Geordie Condor’.