Library and archive volunteer Alan Hart explores some of the wild and wonderful treasures to be found in a bundle of correspondence from the North East Nature Archive

I have just completed transcription of some bundles of letters written to the Society from 1880 to 1898. The letters are usually about some aspect of animal natural history (only a few about plants). I found transcribing them as being like an explorer on a wide plain with little fires dotted here and there which invited further investigation. So, here are some examples of little fires which I think shine a light on concerns of 19th century correspondents to the Society.

The ‘Esquimaux Dog’

In 1891, Edwin Brough sent letters to the Society concerning the skin and bones of an “Esquimaux Dog”, which seemed to have won medal (s) at Crufts. He also offered a bloodhound skeleton, and the body of a bloodhound pup should the Society want it.

Edwin Brough was a well-known bloodhound breeder at Wyngate (now known as Scalby Manor, Yorkshire). Two of his bloodhounds were brought into the search for ‘Jack the Ripper’ but any scent left by the scoundrel had either faded or were never there in the first place.

A day out

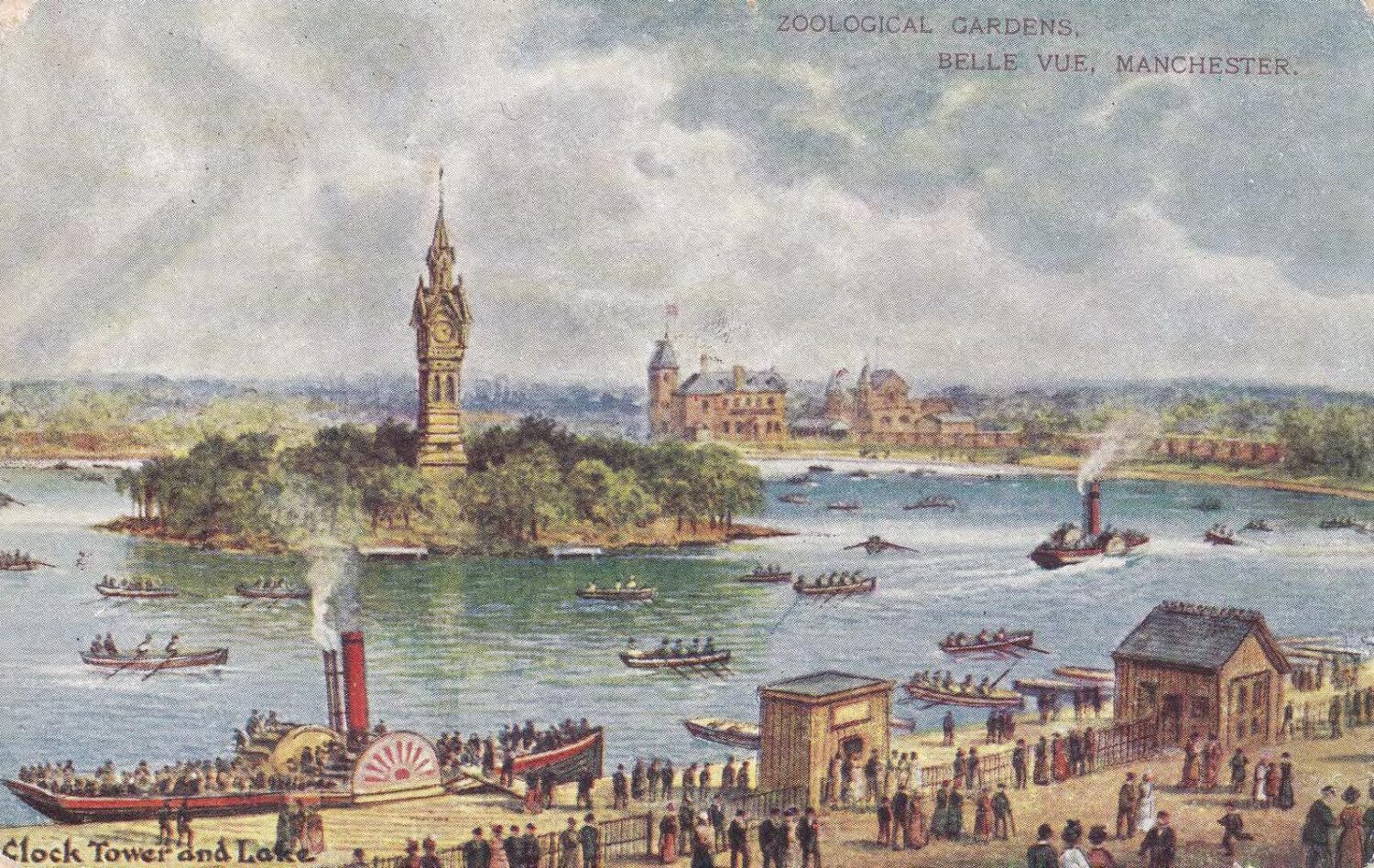

Fancy a day out in 1898? What about a visit to the Zoological Gardens, Belle Vue, Manchester? The Gardens opened in 1863 and eventually encompassed the third largest zoo in the UK. They were enormously popular and provided facilities for huge crowds of visitors. They persisted well into the 20th century; you can read about them in a comprehensive entry in Wikipedia.

At various times the zoo became something of a repository for animals unable to find a home elsewhere. In June 1898 the Natural History Society of Northumberland appears to have been in the possession of a Huanaco (also called Guanaco) – an animal native to South America closely related to the llama. Correspondence between the Gardens and the Society shows that the animal was safely transferred to the Belle Vue zoo. The correspondence does not show how the Society came to have the live animal.

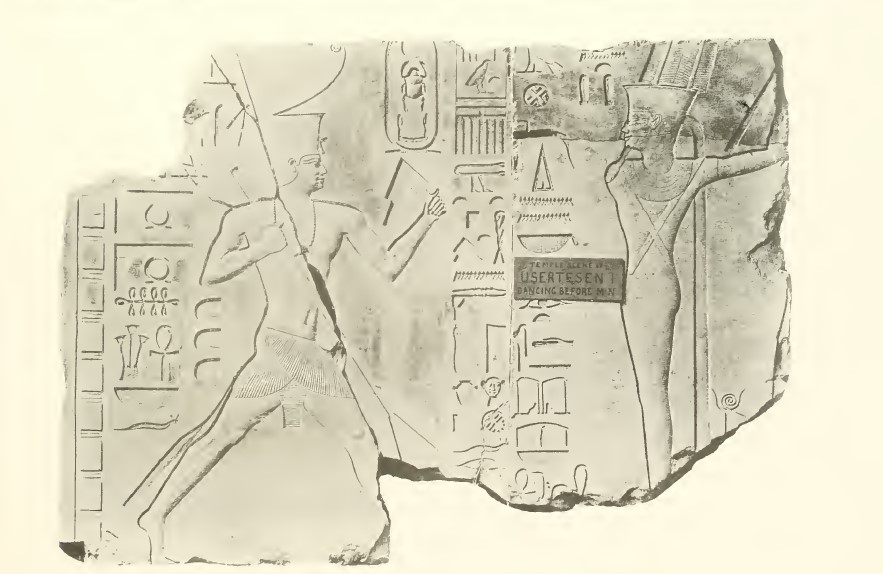

A ‘Great Man’ of modern archeology

Members of the Society in the autumn of 1895 could come to a lecture by Flinders Petrie. He was a “great man”, indeed a great archaeologist who set archaeology on a modern footing, and no doubt also contributed to the craze for Egyptology. As an adjunct to his lecture he also offered to give a couple of cases of Egyptian pottery to the Society.

Unfortunately for his modern reputation, he was also an ardent proponent of eugenics.

In the service of empire

Some of the correspondents were in service of the Empire far away from Newcastle. In August 1891, Captain Ellison of the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) Border Police asks if the Society would like some specimens of beetles and scorpions which he has collected at Barns Drift from the banks of the Crocodile River. He sends the letter from Macloutsie Camp, Northern Protectorate, South Africa. Captain Ellison was also a member of the 1st Royal Dragoons.

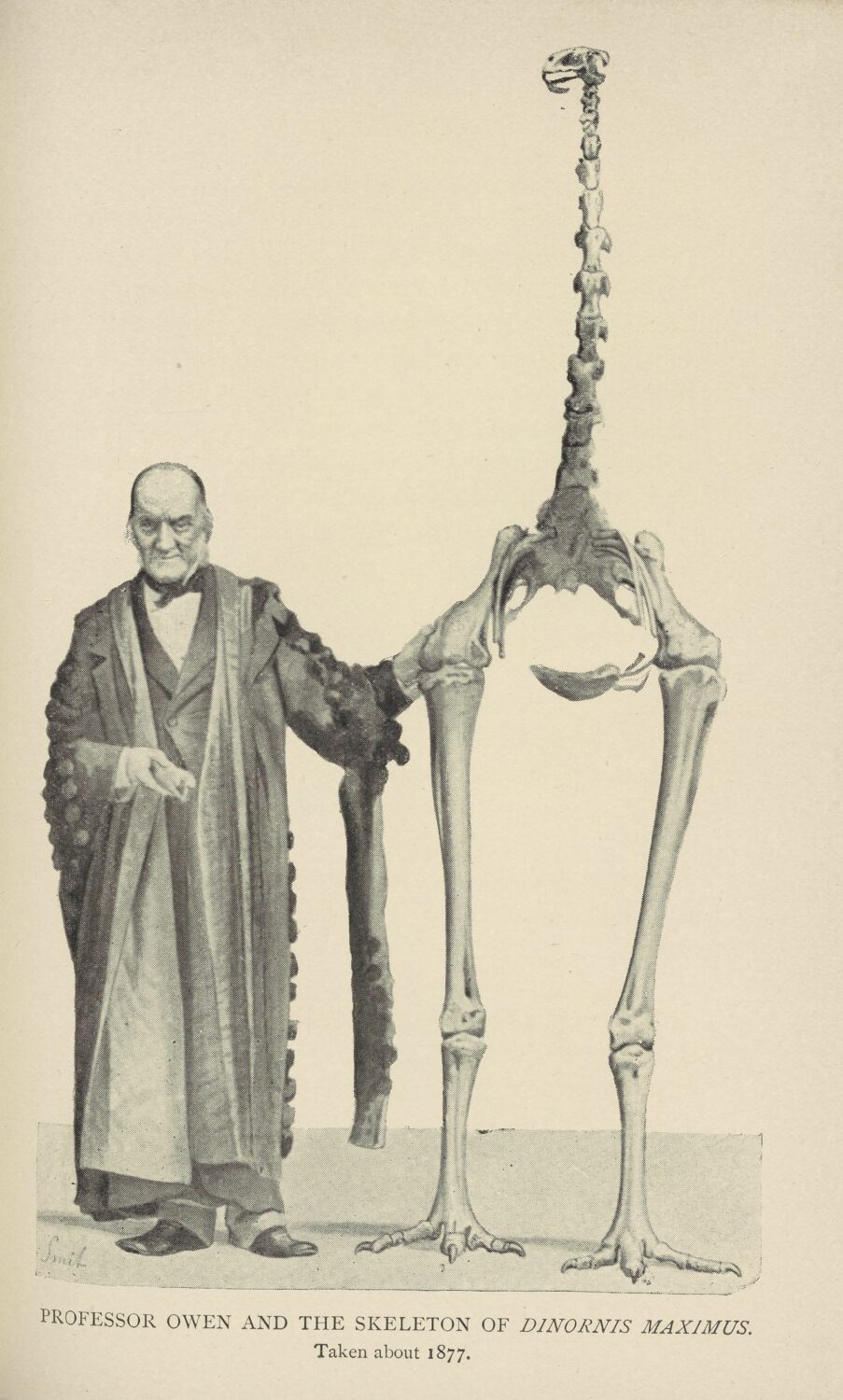

The farthest land, the biggest bird

The British Empire really did extend to distant places. For emigrants from Britain, one of the most distant places was New Zealand. It had a flora and fauna quite different to that of the British Isles, and specimens were no doubt of interest to members of the Society. Some letters indicate there was a flow of objects, originating from NZ, into Britain, and sometimes offered to the Society.

One letter (a single sentence, 1895) asks if the Society would like to acquire some moa bones. The European discovery of the moa, an extinct flightless bird, with some species the size of an ostrich, first identified and described (1839 – 1843) by Richard Owen (anatomist and palaeologist) was one of the major ornithological events of the 19th century. (See Berentson, Q, 2012; Moa, The life and death of New Zealand’s legendary bird, Craig Potton Publishing. This book is in the NHSN library collection at the Great North Museum: Hancock.)

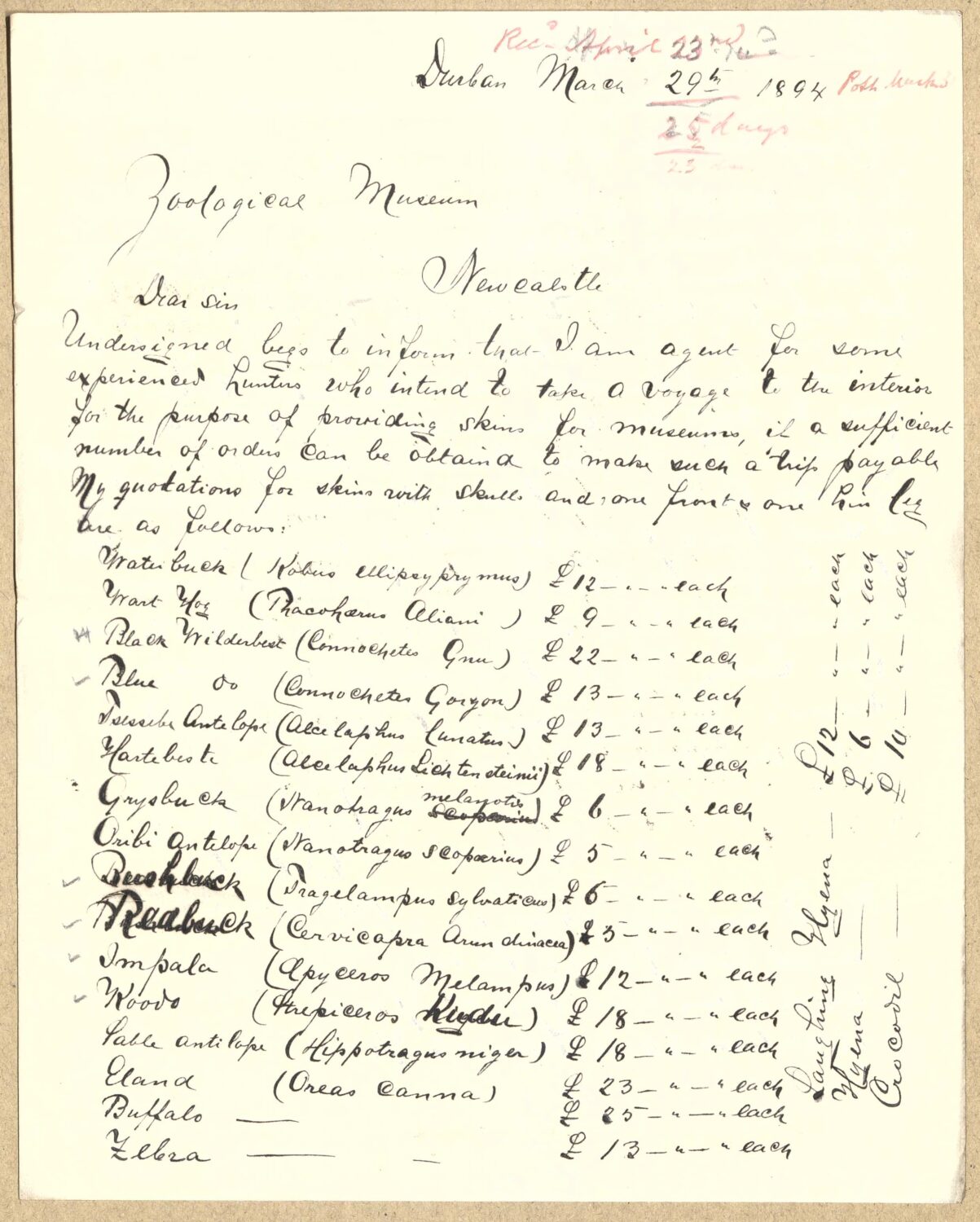

The difference between collecting and killing

The letters were written at a time when it was still common for the response to local sightings of rare birds and animals to be to kill them and offer the corpse to the Museum for taxidermy. Letters from 1890 discuss techniques for the preservation of fishes from a taxidermist in Jersey.

The flow of animals to taxidermists can perhaps be understood in the absence of photography of the kind we have today. One attitude to wild animals which seems particularly unpleasant to modern sensibility is the killing to order of large animals in countries across Africa. In March 1894, an agent for “experienced hunters” sent a price list of animals that the Society may care to have shot for display in the Museum. For example, an eland would cost £23, a pair of lions £55 or even an hippopotamus for £93. (These are substantial sums; about equivalent to £3800, £9000 and £15000 in today’s money, respectively.)

…and not just animals

In 1892, a naval surgeon wrote to say that he had recently returned from Australia with a collection of curiosities and would the Museum like some of them. The items included mummified human heads. Perhaps he had his own private curiosity, influenced by his medical training, but his attitudes may also have been influenced by the attempts of the period to classify bodies of supposed inferior races according to anatomical differences.

The case of the collapsing shells

No, this is not one of Sherlock Holmes cases. A letter of 28 Nov, 1897, notes that shells in the British Museum were decaying on the production of a ‘white deposit’. The correspondent says he has been told that shells in the Alder Collection in the Hancock Museum have suffered the same fate, ending up as ‘lumps of chalk’. He thinks that the cause may be acid fumes arising from the fermentation of gum. A further letter indicates that a box of shells had been sent for analysis but unfortunately there is no further correspondence on the matter.,

Calcium carbonate would seem the most likely candidate to be attacked by noxious fumes. Gas lamps could have been a source of acid fumes, although the Hancock Museum seems to have been lit by electric light earlier than 1897.