Mel Tuckett, Heritage Researcher, introduces our latest blog which explores a difficult period for NHSN, the 1930s and 40s

On being asked to conserve an unremarkable and unpromising looking box, North East Nature Archive volunteer Margaret Heatley discovered an important yet little recognised snapshot of NHSN history. In this blog she shares her fascinating insight into what she learned about the difficult years for NHSN around World War Two. For her these were not normal times as regular members activities and publications had to stop. Yet due to the resilience of a few dedicated people who ran the Society, NHSN battled through to become the modern organisation we enjoy today.

The box

When I opened the box it seemed at first to be just a jumble of unremarkable papers and envelopes. Not a pretty sight or an exciting prospect! Yet when I explored it further, it took me back to a fascinating time when the Society’s affairs were conducted by people from a bygone era, dealing with difficult modern times. I feel that these people held the Society in trust during these abnormal times, resilient and knowledgeable, using their dedication to breathe life into the Society and enabling it to survive.

The documents cover 1933-1947, a period dominated by the events of the Second World War. Yet this was a time when the people who ran the Society were born in the Victorian and Edwardian periods. My investigations revealed that the documents were entirely between men in positions of importance. Although there was a female Acting and then Deputy Curator during this period called Gladys Muriel Scott, any correspondence she created was not included in this part of the archive. If you would like to find out more about Gladys, you can read a blog by Maureen Flisher on her life and work by using this link.

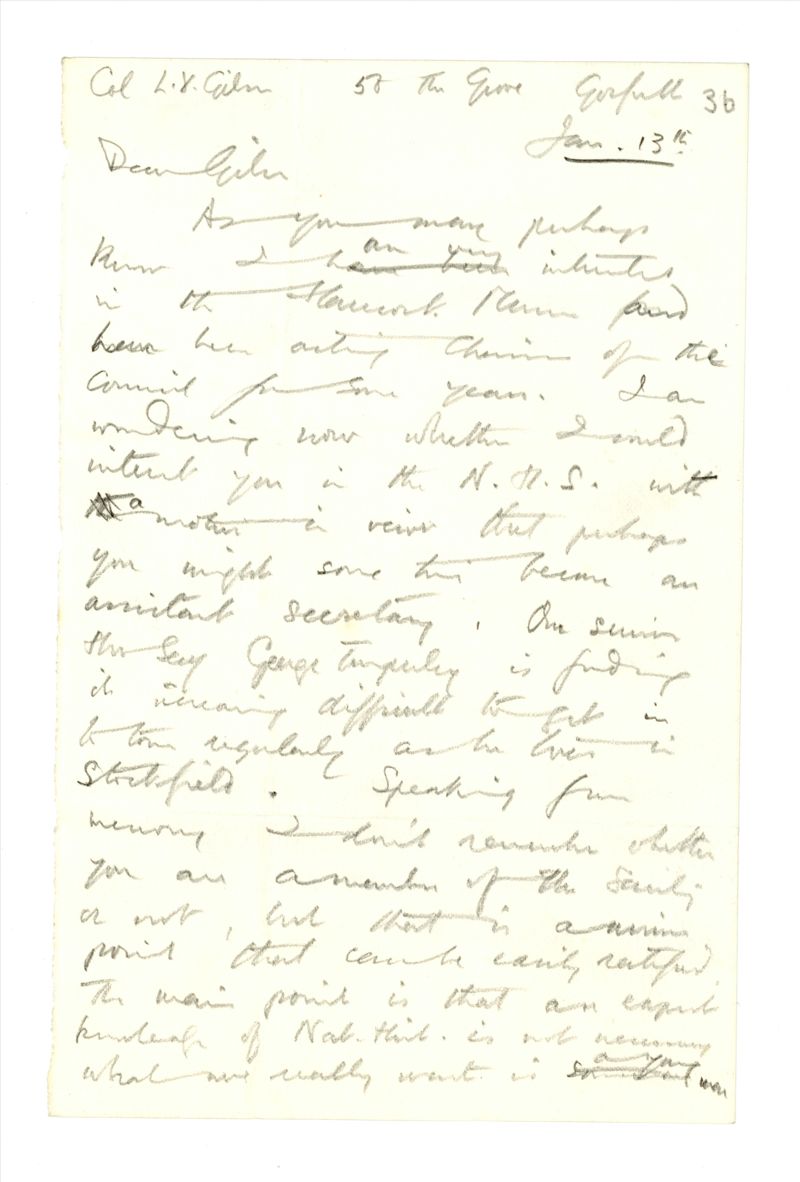

The letters I found gave me a real insight into how things worked during these times. Little clues build a picture of the culture of the men of the Society, creating the impression of a type of gentleman’s club, made up those from the same social class and with similar perspectives.

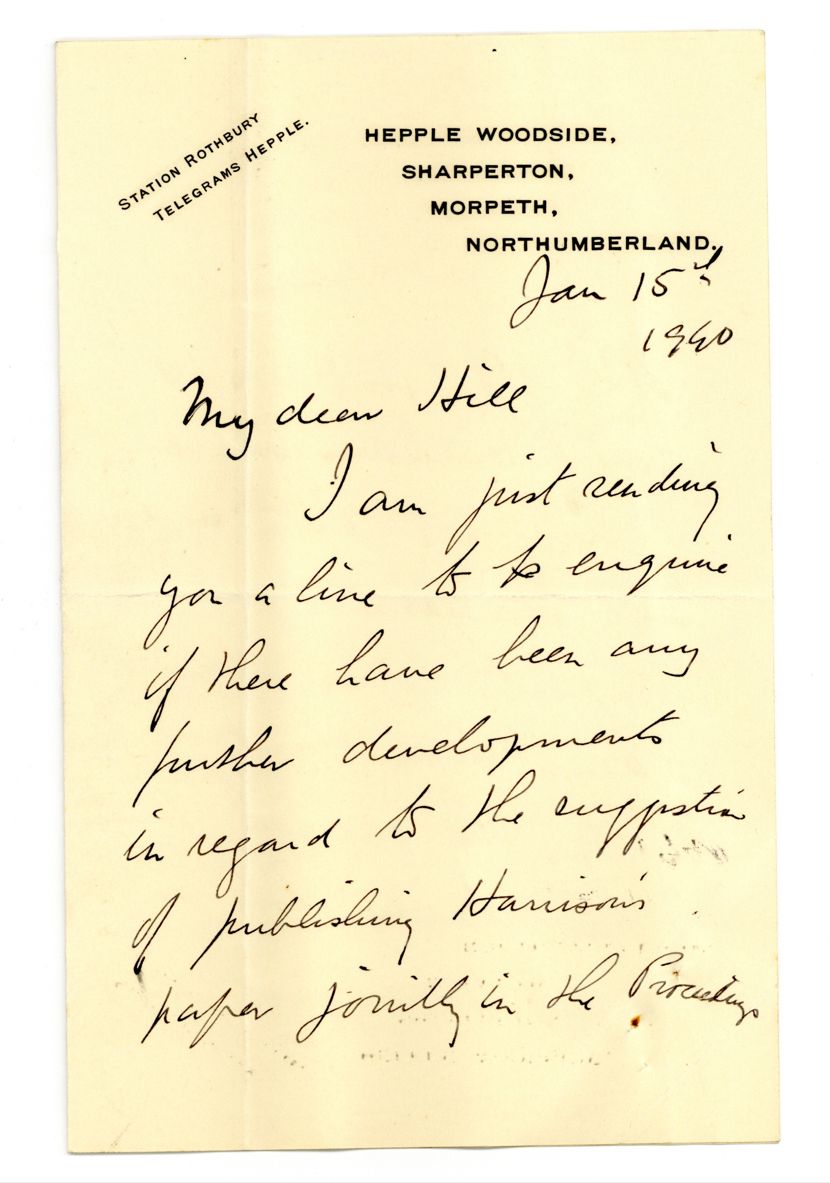

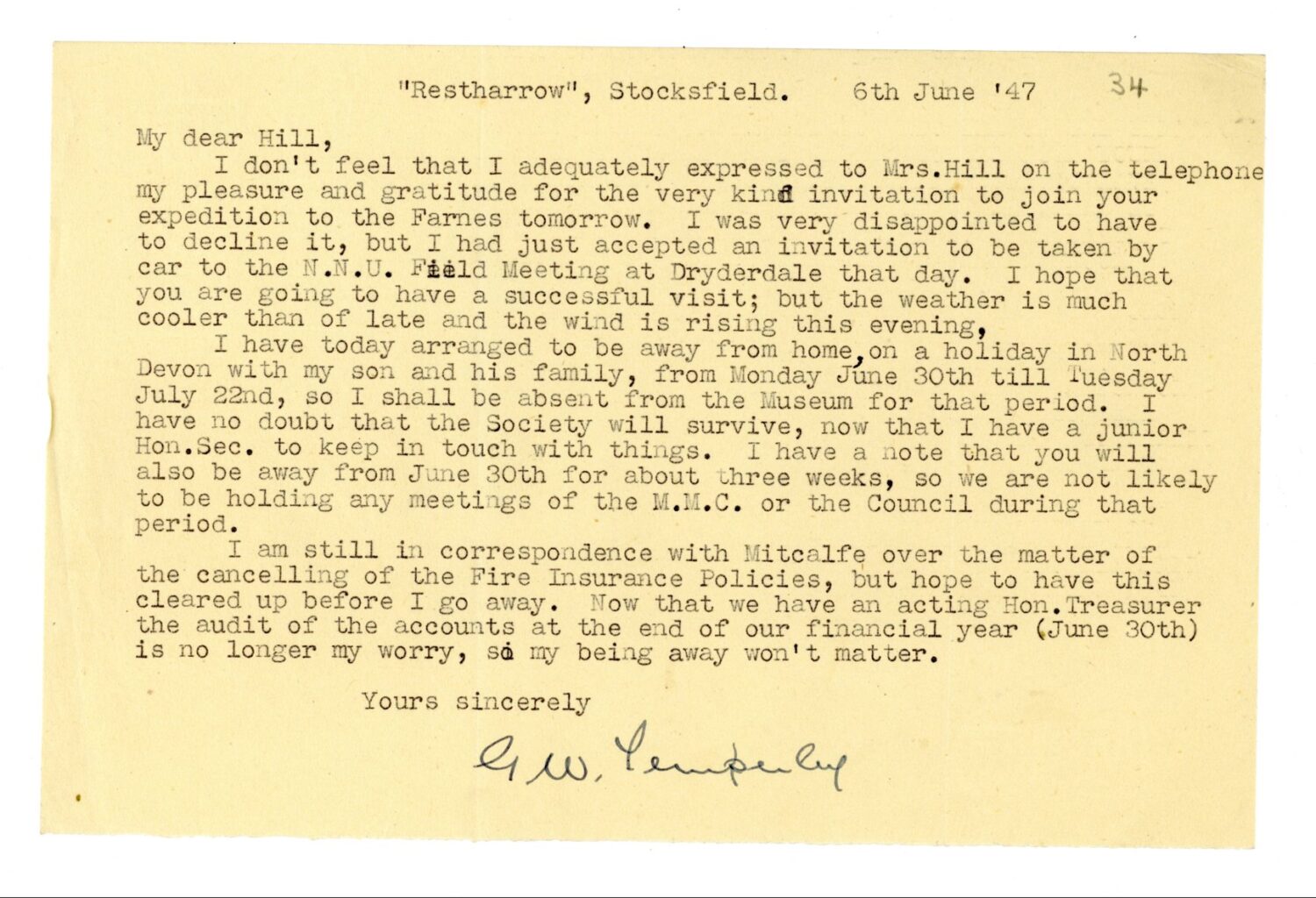

Business was often conducted on personal headed notepaper.

Letters were often written in long hand (and sadly frequently illegible!).

The letters between the men also often open with “My dear Hill,” or “Dear Hill” etc, hinting at the personal connections that existed between them.

Before getting down to business matters, they often ask about the other’s health and give updates on their own. They chat about their family holidays and comment on the weather. Yet they also still retained a certain formality of tone which was common in the understandings to be found between men of certain social classes. For example, the letters are usually signed off with a very polite “Yours sincerely.” The documents also reveal that social status was clearly important. This seems to have been a group of men who knew each other well but who also knew it was important to keep to social rules.

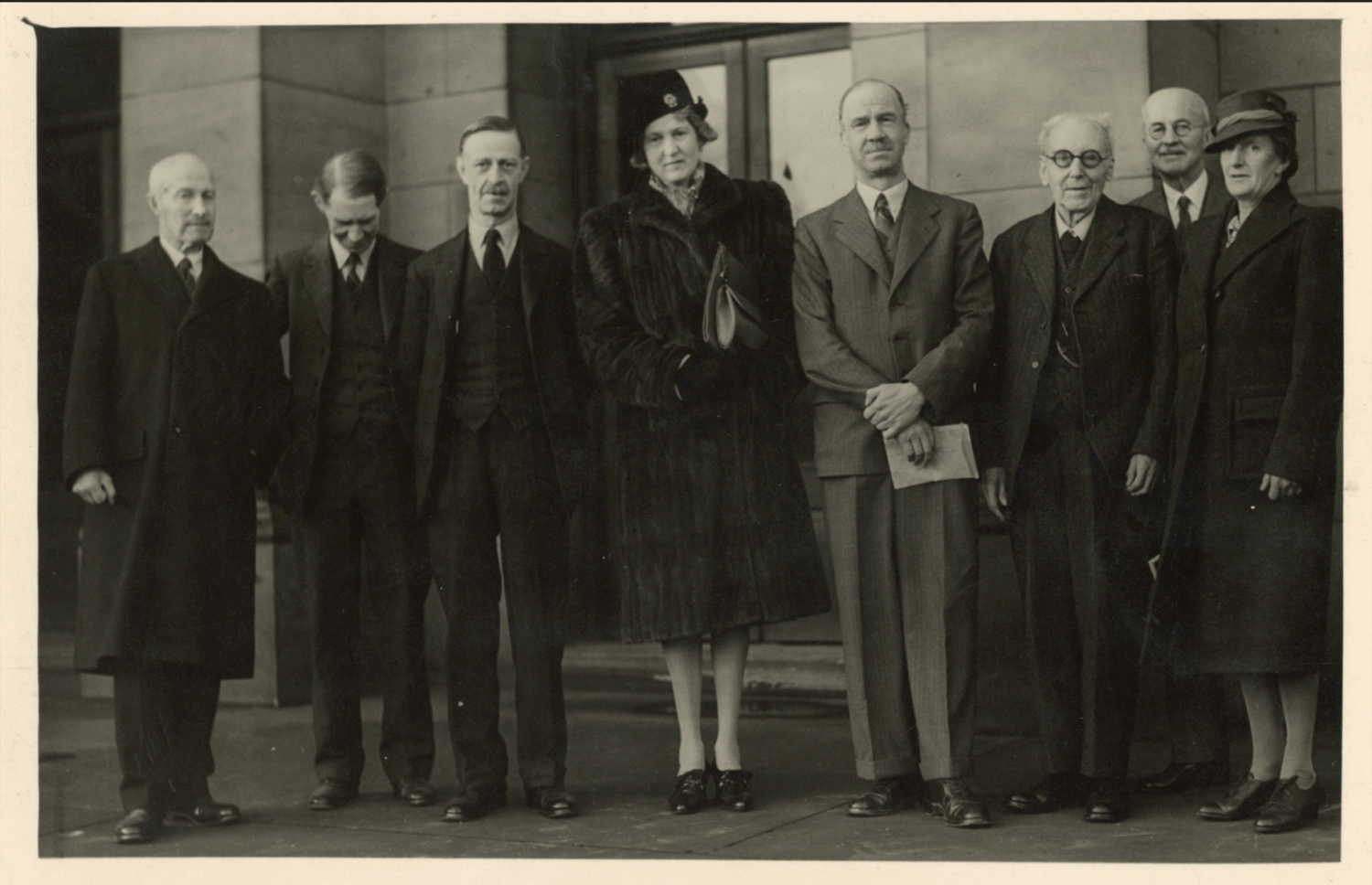

Social status was clearly important within the Society and there was a long hierarchy of presidents, vice presidents, honorary secretaries and council members. So, who were some of the key people?

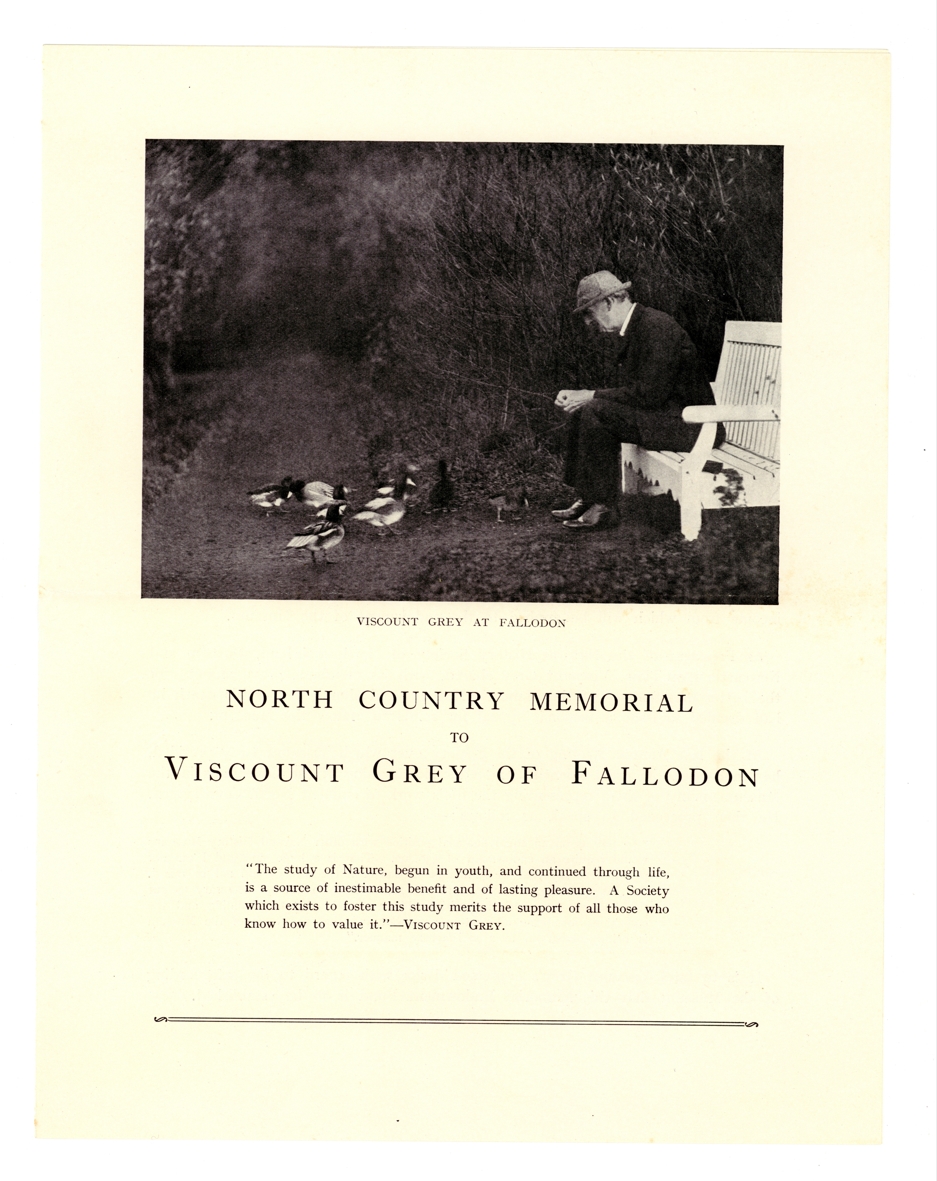

Viscount Sir Edward Grey of Fallodon (1862-1933)

Grey was President of the Society, a great lover of nature and a notable British statesman. He had been Ambassador to the United States, and most famously Foreign Secretary in the lead-up to the First World War: he is the politician who was said to have remarked, on the eve of the war’s outbreak, “[t]he lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.” He died at the beginning of this period but was very influential and held in great affection. A large inscription to commemorate him can be seen to the left of the entrance of the museum. He believed that “[a] study of nature begins in youth and continues through life, a source of inestimable benefit and lasting pleasure”, a value NHSN still holds dear.

George Temperley (1875-1967)

George Temperley was Honorary Secretary of the Society between 1931-1951 and also an Honorary Curator of the Museum. A resident of Stocksfield during this period, he was a nationally recognised ornithologist who carried out many studies and gave lectures. He wrote a key book on the birds of Durham in 1951 and in his role as Recorder of the Ornithological Section of the Hancock Museum, he also collated local bird records. Throughout the war years he worked to keep the collections intact, arranging the British land and freshwater mollusc collection. He was also a skilled botanist and carefully catalogued the holdings of the herbarium to professional standards.

If you would like to know more about George Temperley, writer and artist Mike Collier has researched his life extensively and can be found through this link. And you can also read a blog by fellow archive volunteer Alan Hart on Temperley’s correspondence collection. Click on this link.

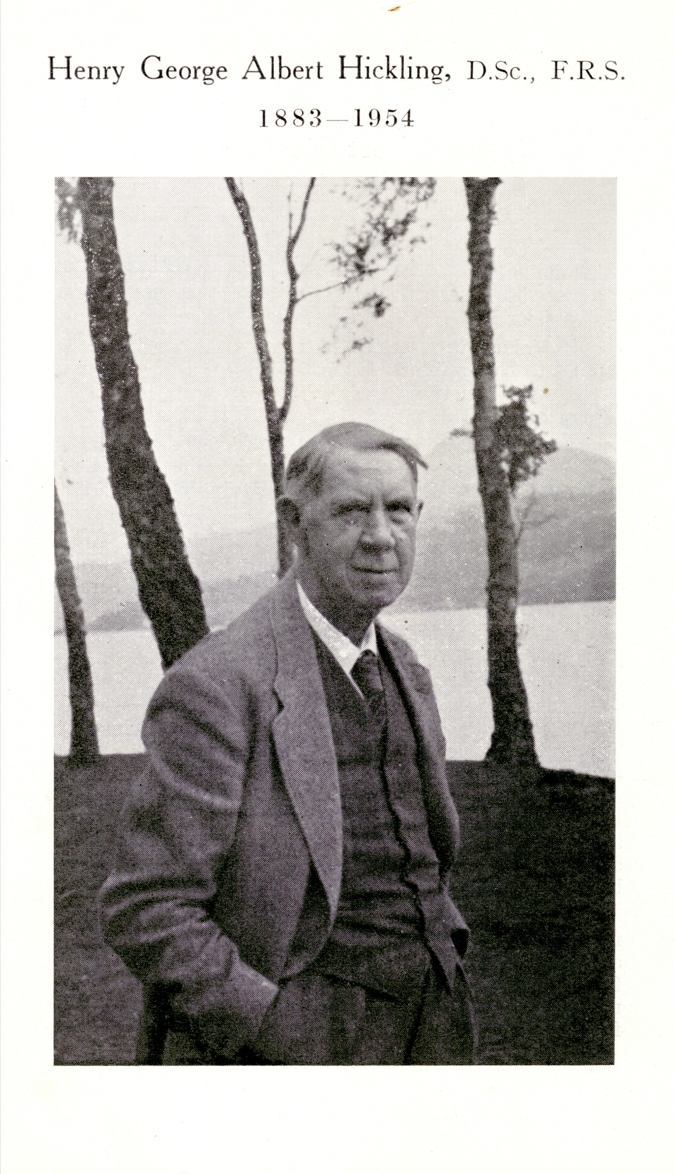

Professor George Hickling (1883-1954)

George Hickling was Vice President of the Society during this period, as well as Chair of the Management Committee. He was also Emeritus Professor of Geology and Palaeontology at King’s College, (later Newcastle University). He used this role to initiate a formal agreement between with the College and the Hancock Museum. The Museum became a university as well as a public facility so that staff and students could use the holdings, library and archive. A new executive management structure was set up comprising a committee including the College’s professors of zoology, geology and botany. The Museum received £1000 per year of much needed funds in return. This was a key moment in the evolution of NHSN and secured its academic and financial standing. George married NHSN Honorary Secretary Grace Watt in 1954, briefly forming a Society power couple before he died after two weeks of marriage.

T. Russell Goddard (1889-1948)

T. Russell Goddard was a leading ornithologist and curator of the Hancock Museum. He oversaw the war time evacuation of the exhibits to less urban sights such as Cragside House and Sharperton in Northumberland, away from the risks of bombs. He also ensured that the Museum itself was protected as windows were boarded up and netting secured. Goddard later became the Society’s historian and wrote the history of its first 100 years. His book is still a prized asset for the Society and available in our library.

If you would like to research this era more fully, other notable council members I found include Charles Robson (1898-1945), A. H. Dickinson (1884-1945), H. L. Hicks, Professor Harrison, Wilfred Hall and B. P. Hill.

Forward together after the War

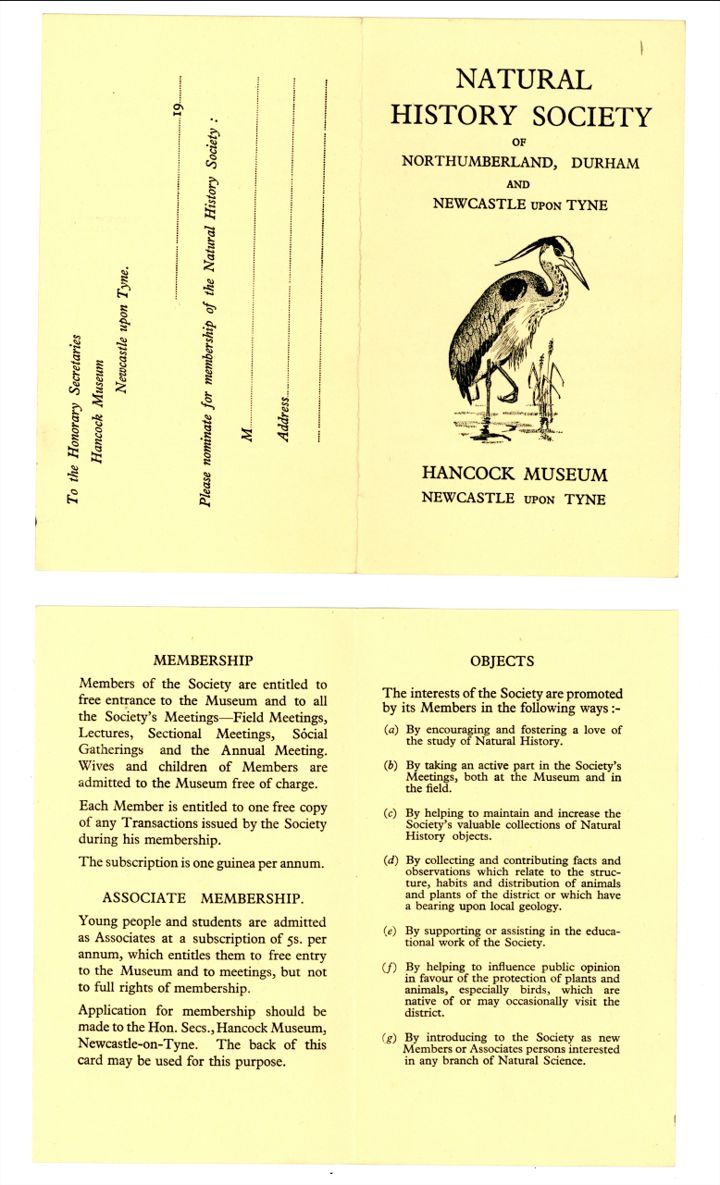

On the return of peace in 1945, these men began the work to build the society’s future. Membership numbers had declined, and full membership dropped by 36%, from 488 to 312, and associate membership dropped by 66%. The Society’s financial future looked at risk as the uncertainty of the period made speculating for funds difficult. Yet eventually, lectures, demonstrations, exhibitions and field study activities began again.

As can be seen in this document, there was a desire to get the Society moving again with a return to a feeling of routine. There is emphasis on reintroducing regular meetings for the society’s members so that reading and discussion could take place alongside demonstrations and social events. Interestingly, the Society used a focus on education to start things up again as well, especially the education of younger people. The museum was run to ensure that specialist students and children could enjoy and learn from the collections as well as adults. A reference library and reading room was established and the first librarian employed.

Also, the specialist scientific work restarted. With the strength and depth of the staff team and membership, the Society’s specialties were able to become active and sectional meetings were established for ornithology, entomology, botany and geology. In the field meetings, lectures and learned papers the scientific knowledge began to flow to awaken the life of the Society.

Onwards and upwards

Since these turbulent times, NHSN has evolved away from the likes of the gentleman’s club and towards the diverse team we see today. Yet it is thanks to these resilient people and their dedication to nature that we enjoy our Society in its current form. They safeguarded the Society through the dark times but came through with a resolution to keep calm and carry on. Wisely they looked to education and scientific advancement as paths forward to the Society’s future and these are still important to us today.

Amongst the many documents in the archive box, I found a quote from the obituary of Viscount Grey of Fallodon which struck a chord with me. Grey was recognised for his emphasis on “the great scientific and educational value of collections in the museum”, highlighting how they represent “the life’s work of eminent north country men.” I am grateful that our Society continues to be able to value and use these collections today thanks to the resilience of a small group of dedicated north country people who steered NHSN through those very difficult times.

Many thanks to Margaret for all her hard work in delving into this fascinating history. Using all her information we can also now catalogue these documents correctly and in excellent detail.