Archive Volunteer Alan Hart explores the botanical correspondence of George W. Temperley, eminent North East Naturalist.

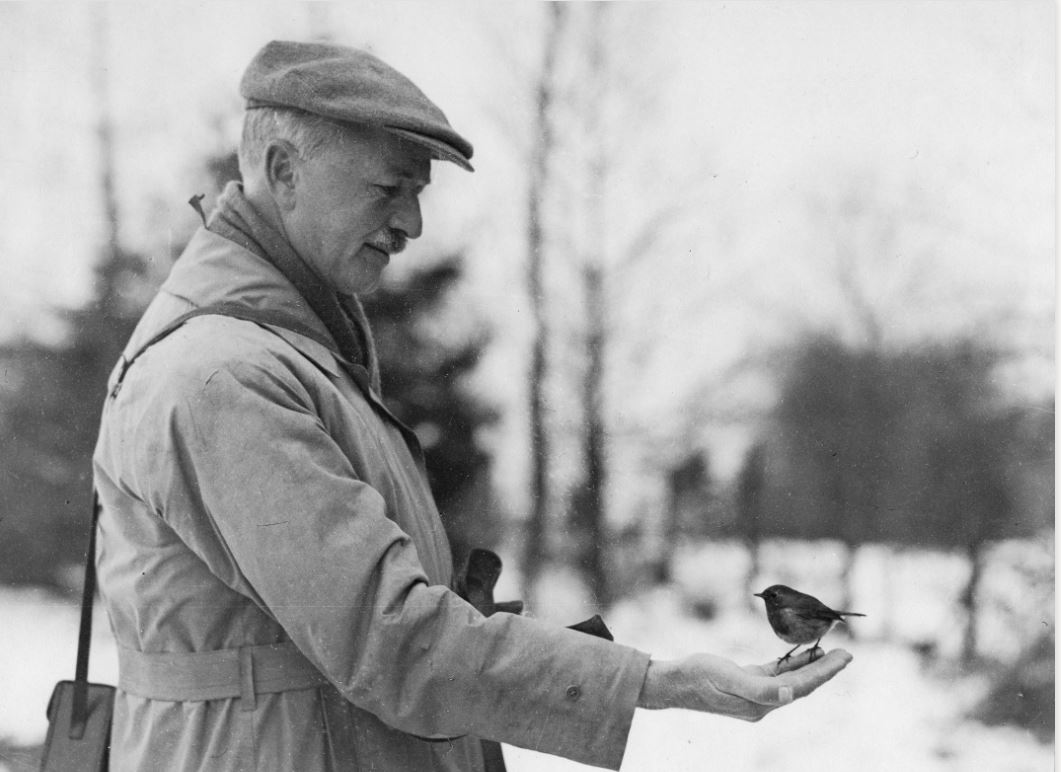

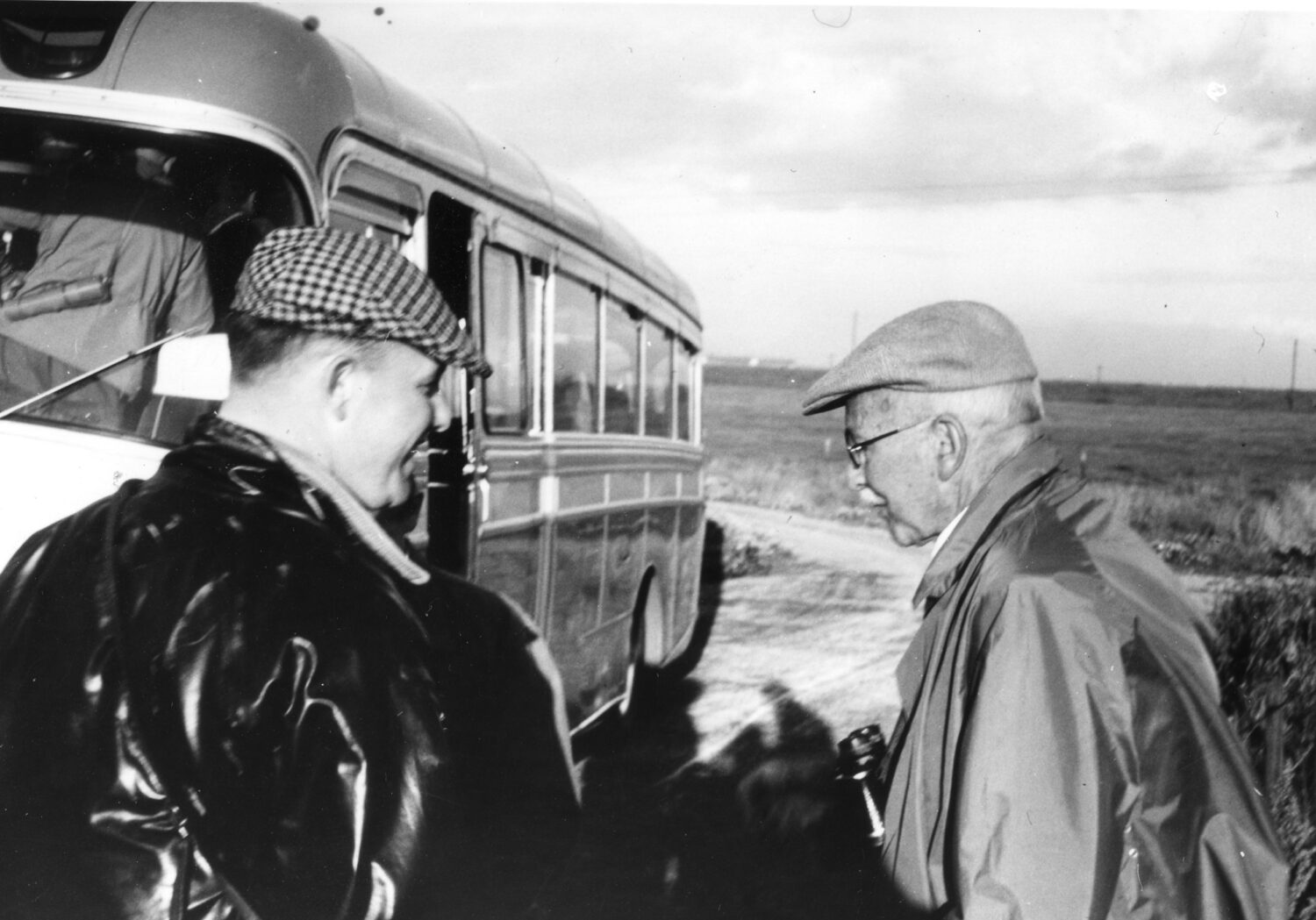

George Temperley (1875-1967) was an eminent naturalist in North East England in the 20th century. He is usually remembered as an ornithologist (Meek, 1983) but he was also a prominent amateur botanist. He was local secretary for the Botanical Society and Exchange Club of the British Isles (BSBI)1 before and after the Second World War, and County Recorder for Northumberland and Durham, though it’s not clear from the correspondence how long he performed this role.

From 1930 to 1951, Temperley was Honorary Secretary of the then-named Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne. He was also Honorary Curator of the Hancock Museum from 1933 to 1939, during which time he worked on the museum’s botanical collections.

NHSN’s archive holds a collection of letters to and from Temperley relating to botanical matters. It contains 120 letters ranging over 16 years from June 1934 to August 1950 – not a particularly large collection for a man of his interests and position. A rather larger correspondence, over a longer period, might be expected. The collection also seems somewhat fragmentary. Perhaps some items are missing or were never retained by Temperley himself.

The subjects in the letters include plants collected on field trips, organising such trips and companions for them, and the location of interesting plants. There are also interesting bits of social history – petrol rationing, finding accommodation in hotels, deaths during wartime – and references to tensions among botanists of the time.

It seems as if some of his correspondents were quite colourful and interesting characters. Two letters in the summer of 1934 are from Gertrude Foggitt (1874 – 1949). She writes about arrangements for a field trip to Teesdale, including accommodation at the High Force Hotel, access to grouse moors and restraint of over-enthusiastic collectors. It appears there were significant numbers of women on the trip, including younger ones. The trip was to be under the auspices of the British Exchange Club and Temperley was to attend.

Gertrude Foggitt’s maiden name was Bacon. As Miss Bacon, she was a keen aeronauticist and collected a remarkable number of firsts: the first woman to make a proper ascent in a balloon, to fly in an airship, to fly in an aeroplane and to be a passenger in a seaplane. She also promoted aeronautics in talks and books. Coming down to earth, as it were, she joined the Wild Flower Society in 1901, apparently with the same application as she brought to aeronautics. Her collection of spermatophytes is in the British Museum, and she made, with Lady Charlotte Davy2, the first discovery of Carex microglohin, the Bristle Sedge, in Britain.

Another notable female amateur botanist (but definitely not a shrinking violet!) who corresponded with Temperley was Maybud Campbell (1903 – 1982). She was independently wealthy, an opera singer, had firm opinions and was a sufficiently skilled botanist to interact with professionals, including those at the Natural History Museum. After WWII, at least, she was Hon. General and Field Secretary of the Botanical Society of the British Isles. In 1957 she acquired a Mediterranean garden at Menton in France. She sold it to the French state in 1966, and the now Jardin Botanique Val-Rahmeh can still be visited today.

Campbell was friends with Dr Alfred J. Wilmott (1888-1950) of the Natural History Museum who was curator of British and European Herbaria. As well as being a talented botanist, Wilmott was a highly strung individual, also with firm opinions. The relationship between Campbell and Wilmott is further discussed in Sabbagh (2016), as it is relevant to the tensions that developed between the pair and John Heslop-Harrison, Professor of Botany in Newcastle upon Tyne, concerning the identity and location of plants, particularly those in the Hebrides. Campbell was on friendly terms with Temperley. For example, she wrote to him on 3rd March 1949 to invite him to stay at her cottage while he went on an excursion, possibly organised by the BSBI, to Breadalbane, Scotland. Ultimately, Temperley was unable to take up the invitation.

The tensions between Campbell, Wilmot and Heslop-Harrison also enveloped other botanists of the period, including Temperley. Just how deep they ran is indicated in a letter to Wilmott from Temperley on 19th January 1947. He relates that he has refused to speak to Heslop-Harrison since 1939 as a result of the ‘vile attacks’ that he made on Campbell in an article published in the journal Vasculum. What had Heslop-Harrison said? The article seems to be Heslop-Harrison et al. (1939). In it, Heslop-Harrison criticises some records published by Campbell. While the comments may seem unnecessarily sarcastic by today’s standards (75 years later), they do not seem so bad as to engender a permanent rift. Nevertheless, Temperley obviously took umbrage at them. The letter to Wilmott also expresses hope that relationships with the Botany Department at Newcastle will improve, now that Heslop-Harrison has retired.

Teesdale was, and still is, an important area for botanizing, and people came not inconsiderable distances to visit it. In 1943, Temperley received a letter from Cyril West, an amateur botanist in Kent, saying that he had visited Teesdale on a previous occasion and that he would like to do so again. It was not until January 1947 that West raised the prospect of a return visit, and the trip went ahead in late June. The trip entailed a small party of West, Temperley and Randall Cooke. A later trip has an extra air of adventure, as it entailed a journey by motor-cycle and side car by Cyril West and another long-time correspondent of Temperley’s, Major Cardew3, from Kent to Scotland, with a stop for botanizing in Teesdale. The pair met Randall Cooke there again, but it is not clear that Temperley went to Teesdale on this occasion. The use of the motorcycle and side car seems to have arisen from rationing at the time; in a letter dated 3 April 1950, West laments that he does not have enough petrol to use a car, unlike his earlier trip in 1947. The High Force Hotel seems to have been the favoured accommodation in Teesdale for botanists on field trips.

During concerns about field trips, plant collecting, obtaining specimens for illustrations in flora, and the appointment of county recorders, there was of course a world war. Among the correspondence is a report on the state of the affairs of the Botanical Society and Exchange Club, dated 1 December 1941, which is explicit about the effect of the war on the Society. The Acting Secretary, Alfred Wilmott, pointed out that it was not possible to publish a report for 1940. Further, in the months leading up to the report, the Treasurer had been killed by enemy action and his records lost, the Editor had died, worn out by excessive war work and the Secretary had been absent on military service since the outbreak of the war. Temporary officers had been appointed, and it was hoped that reduced reports for 1939 and1940-41 would be published. In view of the reduced activities of the Society, the subscription was reduced to five shillings with the intention to charge the usual subscription in 1943. Sufficient optimism was retained to point out that members could still send in records of plants and papers for publication.

Temperley’s correspondents make occasional references to the war. After the war, mention was also made to the dreadful weather in 1946 and 1947. One comment was to the effect that post-war conditions at this time were worse than those during the war, apart, of course, from the absence of hostilities. Austerity engendered by the war continued for some years afterwards, its effects being particularly exaggerated by the severe winter of 1946-7.

In the 1941 report to the BSBI, it is noted that the Acting Treasurer is J. E. Lousley (Job Edward, ‘Ted’) and that Miss E. Vachell (Eleanor) had been co-opted onto the committee. Both were correspondents of Temperley. Eleanor Vachell (1879-1948), like Maybud Campbell, had a private income, which enabled her to travel widely. Prior to changes in the status of women and wider access to universities and professions, a private income would certainly appear to have been an advantage to women wanting to pursue botanical (and other) interests. A member of the Wild Flower Society (and friend of Gertrude Foggitt) Vachell wanted to see every British plant species in its natural habitat and apparently managed to do this, bar 13 species. In a letter to Temperley (undated, but possibly in 1940), she notes that she has seen about 1800 species in situ and seeks his help in finding another – unfortunately her handwriting does not allow certainty about which species she wants to see.

Vachell was Welsh and developed a deep knowledge of the flora of Glamorgan. She became the first woman to be a member of the Council and Court of Governors of the National Museum of Wales. There is a further link to the north-east: she co-authored a paper (Vachell & Blackburn, 1939) with Kathleen Blackburn5.

‘Ted’ Lousley was a banker in London. He had developed a keen interest in natural history as a boy and went on to become an expert amateur botanist. He travelled to every part of the British Isles and built up the largest private herbarium in the Isles. Among his other botanical interests, he became an expert on introduced plants. He remained living in London during WWII and through visiting bomb sites became the first person to officially discover the American willow herb6 (Epilobium ciliatum) growing there. These interests and expertise no doubt helped lead to his appointment as secretary to the Botanical Society of the British Isles in 1950, on the death of Alfred Wilmott.

The correspondence of George Temperley shows that he was part of the botanical establishment in Britain in the 20th century. It shows how strong the links were between amateur and professional botanists, and the importance of contributions of ‘natural historians’ to botanical science. It also allows glimpses of the personalities of the botanists of the period, and how social and political events of the time shaped how botanical progress was made.

Please find a complete list of footnotes and references for this article here.

Natural History Archive

Our natural history archive, housed within the Great North Museum: Hancock, is home to thousands of documents, artworks and photographs. It is considered to be a significant regional resource for the study of local social history, the history of art in the North East, and the study of natural history across the region.

You can search our archive online here.