In the fifth instalment of her series of the citizen scientists of the nineteenth-century coalfield, Maureen Flisher traces the journey of a Cramlington miner who made a new life for himself in the USA

In my blog about Joseph Taylor, the Pitman Naturalist from West Cramlington Colliery, I mentioned Alexander Butters, a fellow miner who emigrated to America in the 1850s. The men never met but shared a love of geology and palaeontology, developed a friendship whilst corresponding and swapped specimens of fossil fish by post. This is documented in a letter Alexander sent to a friend in Blyth, Matthew Tate, which the Blyth Weekly News published in October 1891.

There were parts of that letter I simply couldn’t forget. For example, Alexander recounts walking home, hardly able to put one foot after another after “putting four or five score”, meaning pushing anywhere from 80 to 130 tubs of coal from the coalface to a main gallery or shaft. Of working in the North Pit, the galleries of which extended under the North Sea, he writes that “it would be a relief if the sea would only break through and wipe us all out”. Yet the rest of the letter describes a positive man that had achieved a better life and was held in high regard for his knowledge of geology and palaeontology by the State Geologist of Illinois, Amos Henry Worthen, and other eminent scientists of that era.

Using the clues in Alexander’s letter, census records, the Transactions of the NHSN and the Illinois Coal Mine Index, I embarked on an extraordinary journey.

Alex emigrated in the 1850s – inspired like many immigrants, I assume, by the American ideals of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’. In Alexander’s case, his letter implies that he wanted to escape Britain’s rigid class system and seek equality.

He settled in Macoupin County, Illinois, where the Dorsey family had sold off 40,000 acres of land to the North Western Railway, who in turn opened three mines of their own. Alex worked as a Day Labourer in the Gillespie Mining Quadrant in the county seat of Carlinville. This was common practice amongst the miners of the time, simply going to where they were needed most. In 1880 he was recorded as being a miner but, in 1882, B L Dorsey & Son sank their own shaft in this area and, in the coal reports to the Illinois State Geological Survey for 1884 and 1885, he is recorded as Underground Manager of the Dorsey mine, responsible for coal production and the 80 miners working the coal seams. The mine would become idle during 1887 due to strike action and was abandoned in 1889. I can find no trace of Alex’s working life after that point.

In his letter Alexander writes that his interest in geology and palaeontology began in the 1860’s whilst in America and that he became “a particular friend of Amos Henry Worthen”, a self- taught fossil and mineral collector who became the Illinois State Geologist. He was responsible for surveying the entire Illinois area, gathering a number of leading geologists and palaeontologists to work with him. Their work is recorded in an eight volume set of detailed reports published between 1866 and 1890, the last volume after Worthen’s death in 1888.

A search of the volumes identified Alexander’s contribution to that work. In Vol 6, in 1875, Alex is thanked for providing “important information and material derived from coal measure information coal No 5 – examples from roof shale.” Then in Vol 7 for the period 1882-83 Alex is mentioned more regularly: “[a]t Gillespie in Macoupin County a shaft has been sunk during the past year by B L Dorsey & Son for the details of which I am indebted to Mr Alexander Butters”. Later in that volume Worthen mentions a previously unknown specimen of vertebrae found by Alexander, which he would name Ctenacanthus buttersi in his honour. This shark fossil is housed in the Smithsonian’s Frank Springer collection, Springer being one of the eminent scientists Worthen worked with. Alex sold his own fossil collection to Mr Worthen for the State of Illinois for $1000.

Alex stated in his letter “if I be spared” that he hoped to come to England to meet Joseph Taylor in person, “spend some time going through his collection with him with pleasure,” and also make the acquaintance of John Salt. In May 1892, Alex did return to the North East and visited the NHSN at the Hancock Museum. The NHSN Transactions record that he donated to the Museum collection several American coal measure fossils, a Native American pipe from the White Cloud Company, a stuffed toad from California, a spider from Kansas and two volumes of the final Worthen publication. I believe all are still in our collection.

The NHSN Library also has a book in the John Simm collection by Professor Gurley and S.A. Miller which inside bears Alexander’s signature, along with a compliments slip from Professor Gurley. I can only assume this was a gift to John from Alexander. I like to think therefore that when Alexander returned in 1892, he met up with all three men Joseph Taylor, John Salt and John Simm; they had a good chinwag as they discussed their collections and reminisced about their time in Cramlington Colliery. I am sure Alexander’s tales of American life including the Civil War would have been an eye opener too.

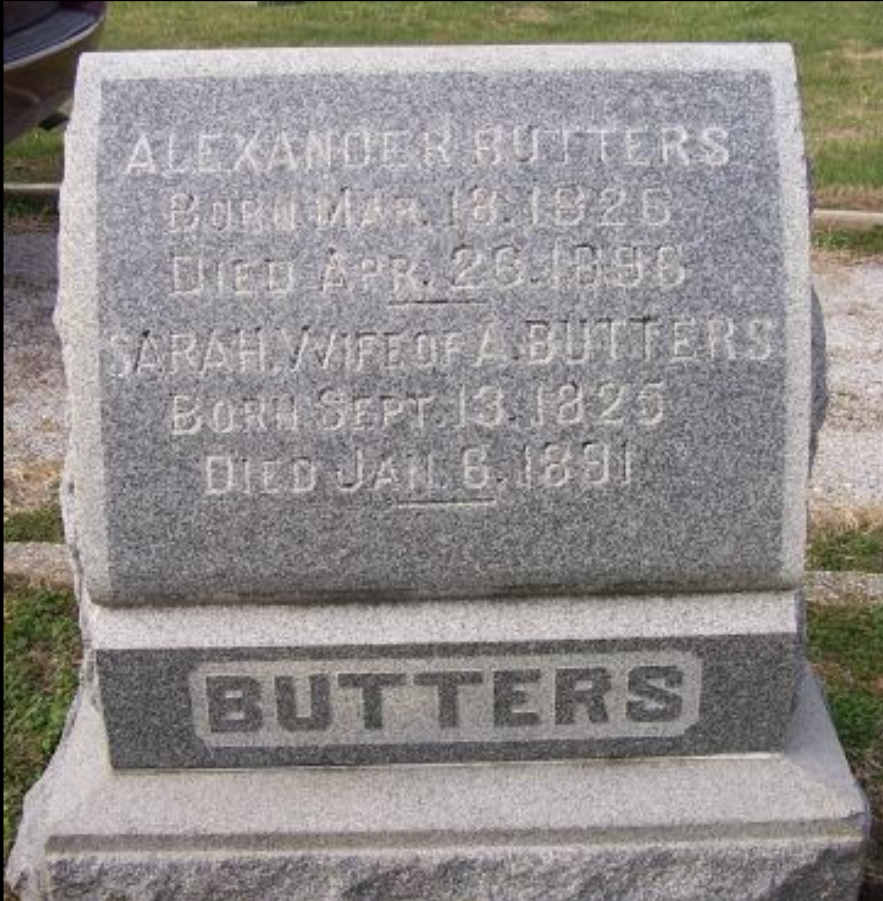

Alexander Butters returned home to America later in 1892 and died in 1896. He had married and had a son who died aged 13. He would later adopt a daughter who married and went on to have children of her own.

I have provided the Smithsonian, the Illinois Centre for Palaeontology and the Illinois Coal Museum at Gillespie with a copy of Alex’s letter from the Blyth Weekly News. The Director and Curator-in-Charge of the Illinois Centre for Palaeontology is Sam Heads – who is originally from Cramlington! He is in the process of identifying all of the Worthen fossil collection and was delighted to hear about Alexander Butters. Should any examples from the low seams of Cramlington, Newsham etc turn up in their Worthen Foreign Collection he would not only recognise them immediately but will let me know.

The author wishes to thank:

Jim Fagan, for newspaper and genealogy research

Dr Sam W. Heads, Illinois Center for Paleontology

Matthew T Miller, Museum Specialist, Dept. of Paleobiology at the Smithsonian

Dave Tucker, Curator, Gillespie Mining Museum, Illinois