Michael Greatbatch explores the work of a forgotten nature diarist in turn-of-the-century Newcastle

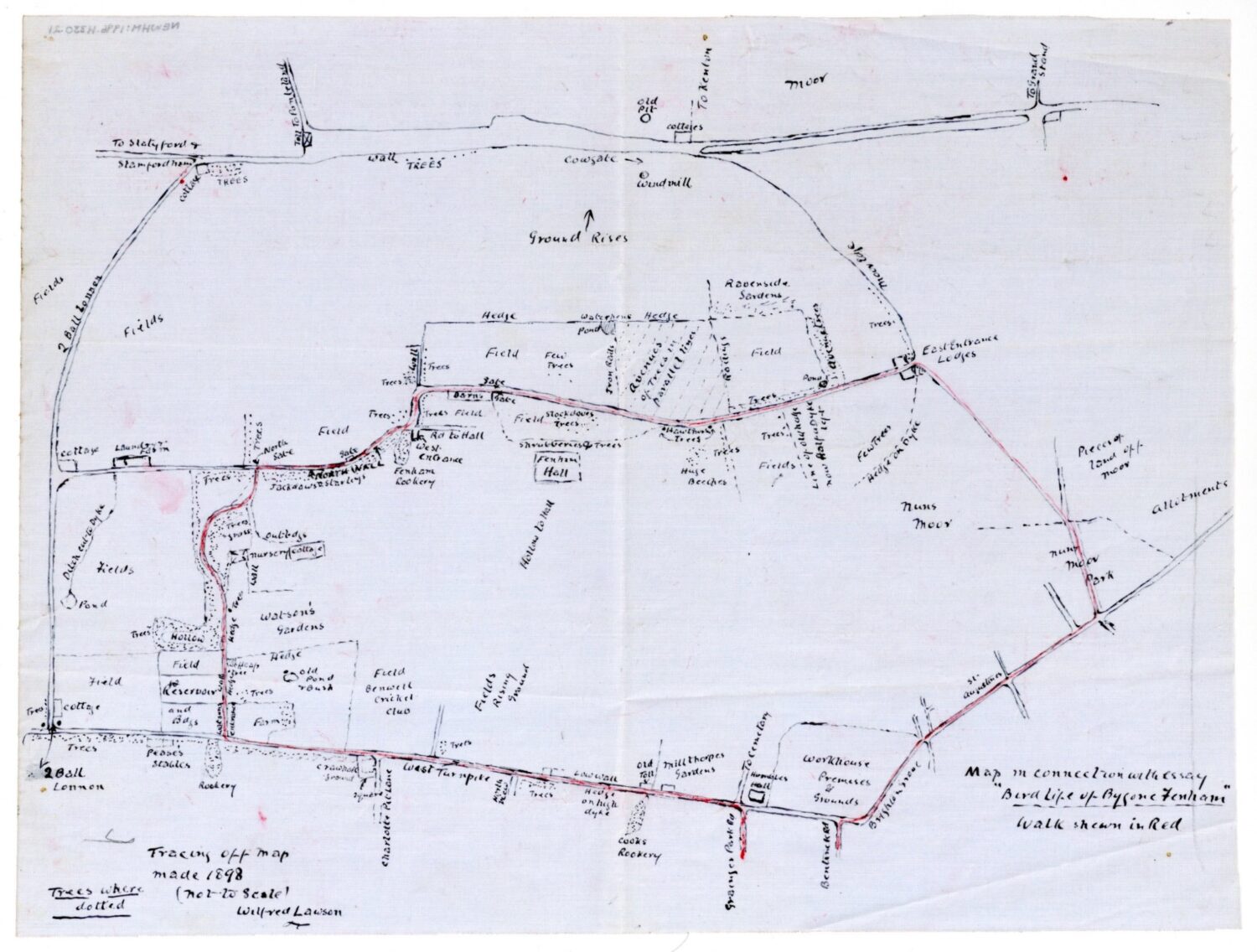

Bird Life of Bygone Fenham is the title of an essay submitted by Wilfred Lawson to the Hancock Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne on 16 November 1944 for the Hancock Essay Prize competition. The essay was based on his diaries, “kept day by day in all natural history observation” whilst taking walks in the Fenham area, and on 29 November Lawson submitted a map ”showing my walk[s] during 1897 – 1904” to accompany his essay. His letters and essay are now part of the North East Nature Archive at NHSN.

The Hancock Essay Prize was an annual competition established in 1893 as a memorial to the life of John Hancock (1808 – 1890), who along with his brother Albany (1806 – 1873) was a leading light of the NHSN in the nineteenth century, and prime mover in the construction of the Newcastle Museum of Natural History – renamed the Hancock Museum in John and Albany’s honour after their deaths, and now Great North Museum: Hancock. The prize was aimed at encouraging an interest in nature by young people, and was worth £5; it was awarded for an essay on natural history that provided evidence of personal observation and study. The winner in 1944 was Kenneth Park.

Wilfred Lawson’s essay takes the form of a description of the footpaths and lanes that he took on his daily walks around Fenham Hall, with a running commentary on the birds and other animals he observed on a regular basis during the years that Fenham was being redeveloped as a garden suburb – or, as Lawson describes it, “trees hacked down, hedges destroyed, and the general breaking up of the place, peace and beauty fled”. One of those beautiful places was the Ravenside Garden, where Lawson lived in the years that he wrote his diaries. This walled garden was created by the Graham Clarkes, tenants of the Ord family at Fenham Hall from 1812 to 1834, the year the Ords sold Fenham Hall and much of the surrounding estate.

Ravenside Garden

The Ravenside Garden was south facing, with a wall on its north, west and east sides, built on high ground above the driveway to Fenham Hall. It was here that James Graham Clarke grew his prize-winning grapes (1830) in a vinery attached to the inside of the north wall; he also won prizes for his geraniums, a gold medal in June 1832 for a collection of 42 varieties `in full flower’, and the following year a silver medal for what one observer called, according to the Newcastle Courant, ”the most beautiful [display] we ever witnessed” At their meeting in July 1826, members of the Horticultural Society enjoyed a dessert of seasonal fruit, including a pineapple supplied by Mrs Clarke of Fenham, no doubt grown in the large greenhouse in the south-west corner of the Garden.

Wilfred Lawson was in his early twenties when he lived in one of the two cottages attached to the Ravenside Garden, and today the site of those cottages (and much of the original garden) is beneath the access lane and adjoining back-gardens behind my own house in Auburn Gardens. I first became aware of Wilfred Lawson and his record of Fenham birdlife in 2017 when I found one of his diaries in Tyne and Wear Archives. My initial interest was in a similar diary that he kept to record his day job at the Ouseburn Forge on what is now Foundry Lane, on the east side of the lower Ouseburn. By a strange quirk of fate, I too worked in an office on that exact same site whilst employed as the manager of a community heritage project, part of the first phase of the Ouseburn’s regeneration from 1998 to 2002. Consequently, Wilfred Lawson and I have much in common: we both commuted to work and back from almost exactly the same locations, and we have both taken daily walks around Fenham; and whilst I am a scholar of human rather than natural history, I too am aware of the birds and other wildlife that today populate this district of ”bricks and mortar”, as Lawson was apt to describe the encroaching urban environment.

The Fenham Estate

The Fenham estate was purchased by the Northern Allotment Society in May 1898, and their development company, the Fenham Estates Company Ltd, immediately began surveying the area for new roads and houses, the latter to be sold as freehold to the growing number of professional and business people who could afford a mortgage. The first phase of this suburban development was Wingrove Road, linking Westgate Road to Cowgate and the Ponteland Road; a price plan dated 01 February 1899 details the individual house plots and the estimated price that these houses might fetch when built and sold. This change in land use was something that Wilfred Lawson would have witnessed on his daily walks, involving as it undoubtedly did the felling of trees and the excavation of grassland and meadow.

Auburn Gardens was part of the third phase of the suburban development of Fenham, the first houses being built in 1909/10, not long after Lawson left the area; in 1944 he was living in Monkseaton, Whitley Bay. In his essay Lawson describes the landscape immediately south of the Ravenside Garden, the trees that bordered the south and east side of an open field, the starlings that nested in those trees (“just about every hole in the trees taken”), and the redwing that fed in the short grass of the open field. This field was grazed by livestock belonging to White House Farm, at the top of what later became a development of large villas called Moorside; today some the trees described by Lawson survive in the gardens that back onto Wingrove Road north of Fenham Hall Drive, and some of the trees lining Moorside North must also date from before the houses were built.

If starlings were the most common bird in this corner of Fenham, Lawson tells us that the next most common was the blackbird, including one rather rare sighting:

One could stand and count up to a dozen in view. During the period of my frequenting the place I only came across one pied blackbird on the estate. One winter’s morning and when scarcely dawn I saw an apparently headless blackbird on the snow along by the north wall. It was not until some mornings later I discovered it was a blackbird with a pure white head and neck marked off as sharply from the black plumage as a Dutch rabbit. I followed his comings & goings for 4 years until one severe wintry spell I saw him perched on railings in a street about a mile away, and that was his last appearance.

Accompanying Lawson on his regular walks were his dogs, whom he exercised in the evenings and early mornings; his one surviving diary is titled ”morning walks before 8 am”. He generally traversed a circular route that took in Nuns Moor Park, Brighton Grove and Westgate Road where he would turn north through ”a narrow door between the Reservoir & Gowlands Farm” into a narrow and winding pathway with grassland and clumps of trees either side that led towards the west driveway of Fenham Hall; today much of this area is covered by Westgate College, and the former driveway is now Cedar Road and Convent Road. East of this pathway was a pond and an extensive nursery (Watson’s Gardens), with large trees bordering the path, ”our way winding in and out of them and rough undergrowth, parts of fallen trees rotting, and coarse grass”.

This mix of trees, grass and water provided a rich habitat for birds, and Lawson’s description includes the following: ”[t]he fields & dene on left side were frequented by partridges and pheasants and trees about [the] path by starlings, chaffinches, willow wrens, and usual songsters”. Near the wall lining the driveway he recorded starlings and jackdaws, and in the trees north of the driveway he frequently heard the long drawn out `co-co-coo’ of brown owls. Approaching the West Lodge of the Hall, Lawson tells us that at one time he could count up to forty nests in a large rookery whose occupants would fly south to visit another rookery near the reservoir and then fly back again. West of Fenham rookery was the favourite site of willow wrens: ”They sang all over the estate but this was where I first heard them each season”.

Beyond the West Lodge and the rookery the lane descended downhill where, Lawson tells us, ”one might see an occasional rabbit, and in the trees stockdoves”. At this point the lane turned sharply east and continued thus until it reached the two East Lodges and the Nuns Moor beyond. Today this is Fenham Hall Drive, and Lawson describes the landscape north of this east drive as being divided into three fields by iron railings, enclosed by a hedge along the north side where a pond surrounded by reeds was home to waterhens. In one of his original diary entries, dated 17 April 1899, Lawson describes the scene on exiting the Ravenside Garden:

Few flakes of snow at 6 am. At 7 am came away snow from a huge cloud in NW for half an hour. A number of lambs in field S of Ravenside Gardens. They generally get through railings & play around an old rotten tree stump. But this morning were lying down with backs to the weather.

The middle one of these three fields was planted with huge old trees, providing cover for partridges, pheasants and hares. Sadly, these trees were felled to create space for what the Fenham Estates Company Ltd called the ‘Garden Streets’, of which Auburn Gardens was the furthest east, directly below the Ravenside Garden.

Birdlife in Fenham today

In his diary, written between April 1899 and September 1900, Lawson records flocks of birds observed on his daily walks. Today the numbers are far fewer, and even the familiar garden birds – robin, blackbird, thrush, sparrow, and members of the tit family – are less obvious and less numerous than even ten or twenty years ago. In spring and early summer you can still hear the song of a blackbird but for much of the year it is magpies and pigeons that tend to be the most frequently seen birds in Auburn Gardens and adjacent streets.

Fenham became a sought-after residential location because, although near to Newcastle, it is separated from the city centre by Nuns Moor, a large expanse of open grassland. When the Ponteland Road was diverted northwards to Cow Hill in the 1980s, this left an avenue of mature trees, free of vehicular traffic and now used as a cycle and pedestrian pathway. These trees, together with those that once formed the historic boundary between Newcastle town and the Fenham estate, provide a roosting for jackdaws and crows, and represent one of the few places in Fenham where one can still witness flocks of birds in flight, particularly crows. Today these include ring-necked parakeets, a recent addition to the Fenham skies and certainly not one to be seen by Wilfred Lawson in the early 1900s.

I am reliably informed (by a neighbour) that redwings can still be seen on Nuns Moor, often in the company of their larger relative the fieldfare. Lawson refers to “brown owls”, and whilst the tawny owl still occurs in Newcastle, the landscape around Fenham no longer provides suitable habitat. Likewise pheasant and partridge: both absent except on rare occasions. What Lawson calls “willow wrens” (the willow warbler) are also increasingly rare, though their close relative the chiffchaff is heard in spring in various parts of Fenham, including the Moorside Allotments north of Fenham Hall Drive. These allotments include a number of gardens designed to attract birds and promote habitat; here dunnocks, tree creepers, wrens, chaffinch, goldfinch, and bullfinch have been observed. Other wildlife at the allotments includes foxes and grey squirrels.

One species of bird that Lawson fails to mention in his essay are gulls. Today these are increasingly a common sight (and sound) in Fenham, and a constant reminder of the changes to our natural environment during the century and more since Lawson recorded his diaries ”day by day in all natural history observation”.

In the final page of his essay, Lawson recalls the `many moods’ of the place, ever changing with the seasons and the weather:

The ghostly mists rising off the parklands, for it was foggy here when nowhere else about; the lapwings’ plaintive call, trees looming up dark and grim, leaves falling and the fog drops pattering on them as they lay in the grass. Or after rain, when the sun broke out of a yellow dawn and glinted on the streaming trunks of the avenues and great beeches, and the full chorus of the birds rolled out.

However, by 1904, his last year in Fenham, Lawson recalled the silence and the loss: “That last season there were to be counted 7 nests at the Rookery as seen from the drive and in April, like many of the birds, it too deserted the place for good”.

Wilfred Lawson’s essay provides a wonderful insight to the landscape and habitat of Fenham at a time of fundamental change. Today, in 2025, as the present Government seeks to revive the concept of garden suburbs and new towns, the loss of habitat brought about by such changes makes Lawson’s essay even more valuable as a record of a bygone age.

The author wishes to acknowledge the help of his neighbours in identifying birds seen and heard in Fenham today, and Jonathan Wallace in particular for reading through and commenting on a first draft of this essay.