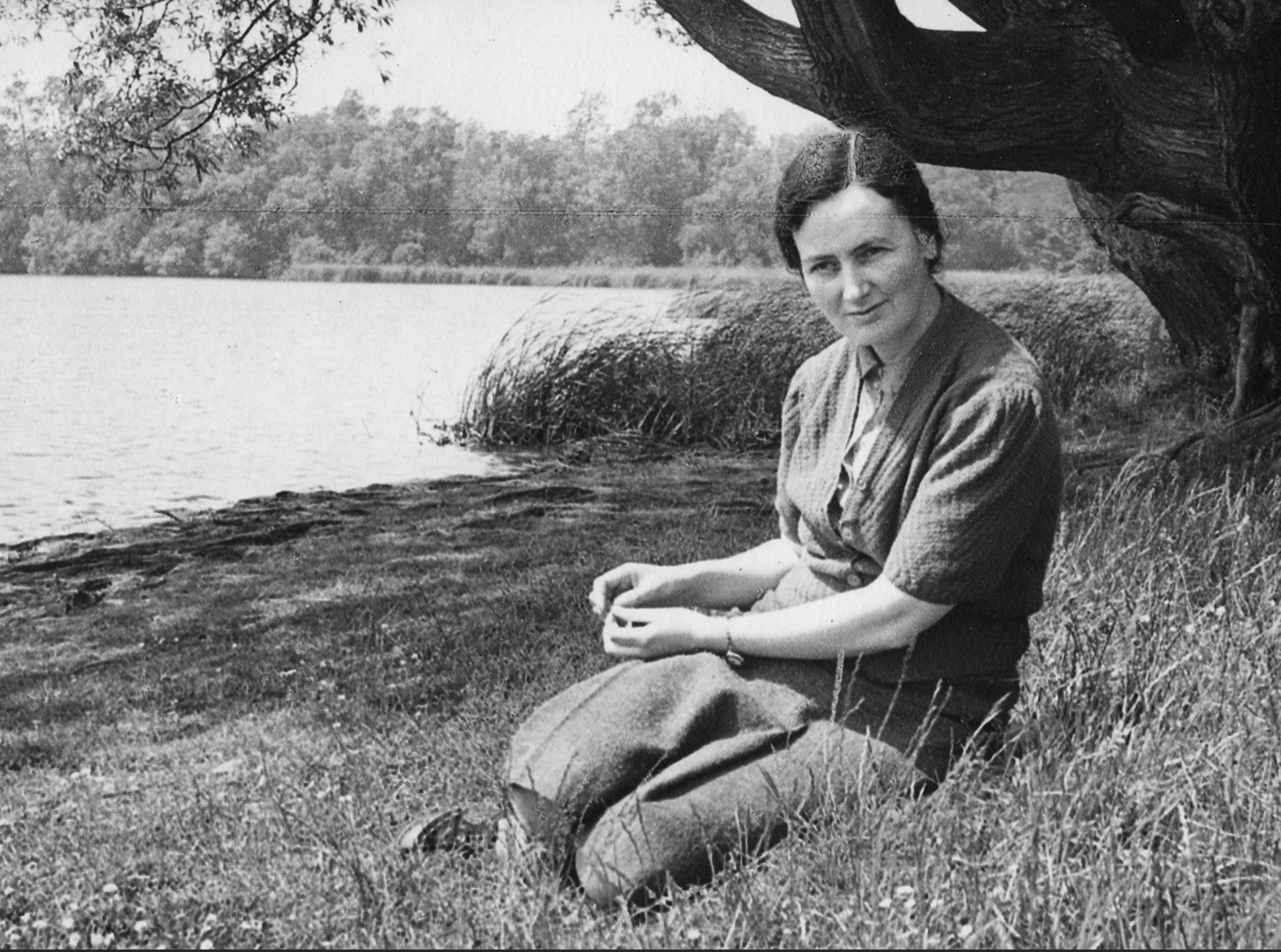

Anne Wilson explores the life of the NHSN’s most famous 20th-century Chair, and the first woman to lead the Society

Grace Hickling dominates the post-war history of the NHSN. The first female head of the NHSN, passionate about the Farne Islands and Northumbrian wildlife in general, and a pioneering expert in grey seal research, Hickling cut a formidable figure. But who was she?

Grace Watt was born on the tenth of August 1908, the only daughter of Adam and Grace Watt.

Her father was an engineer, and after his wife’s death Grace remained at home looking after him until he died in 1969. She was educated at both Harrogate Ladies College and Armstrong College, then gained a degree in geography and mathematics from Newnham College, Cambridge – an achievement of which she was always very proud. After graduation she took up a teaching post, but in 1938, with the threat of war looming after the Munich Crisis, she was asked to receive training to work in a war room in Newcastle. On 1 September 1939 she was called up as one of three intelligence officers working at Watson House in Pilgrim Street.

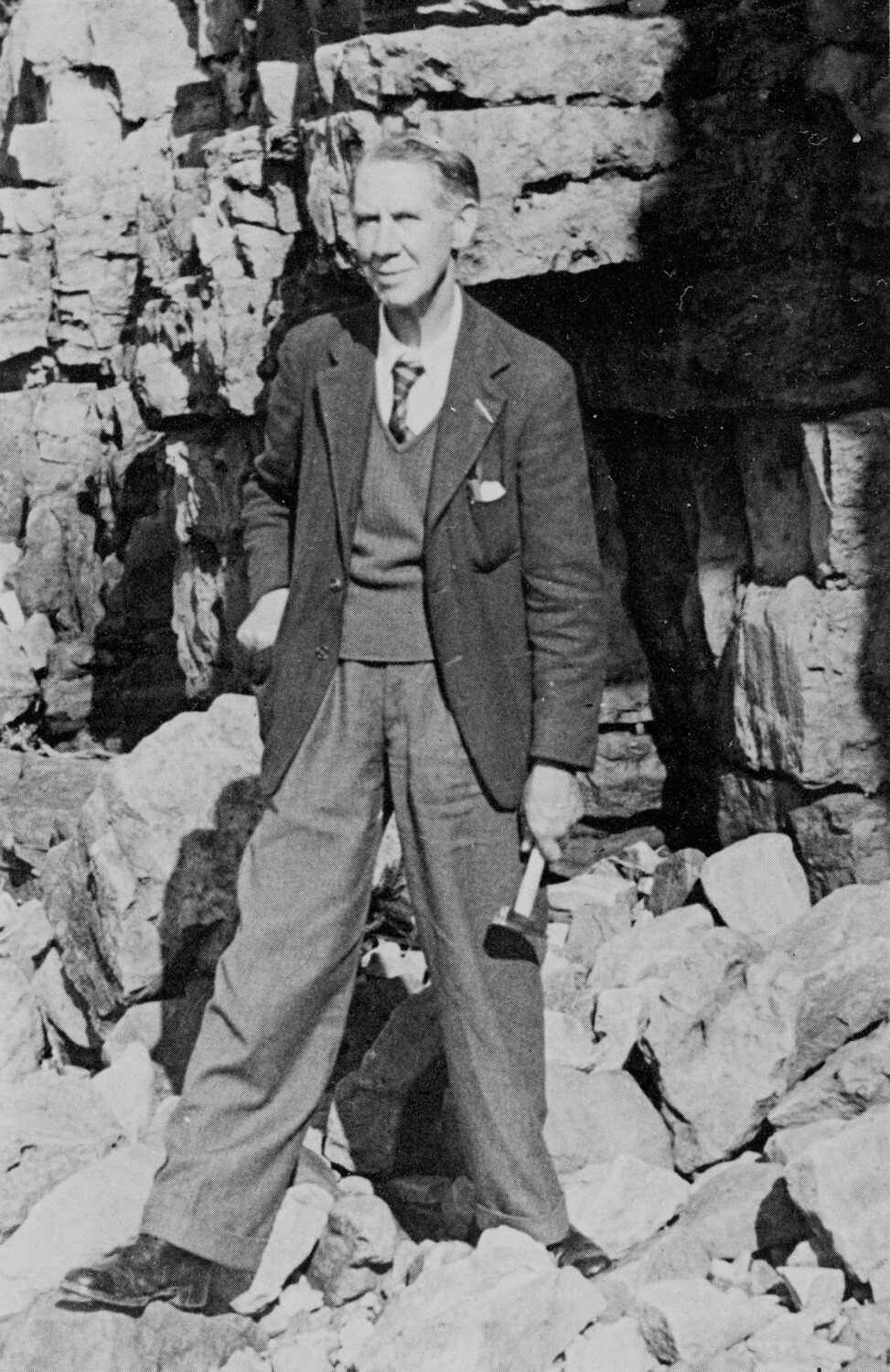

While working in the war room Grace met Tom Russell Goddard, the then curator of the Hancock Museum (now Great North Museum: Hancock), and a leading authority on the wildlife of the Farne Islands. This encounter was to change the course of her life: as Tom talked about both his work and visits to the Farne Islands, her interest was immediately aroused. Her first visit with him in 1940 only deepened this interest further; she was particularly captivated by the Grey Seals.

Grace and Tom became close friends, and after the war she accompanied him to the islands on numerous occasions. When he died in October 1948 she was devastated, and for a while lost some of her enthusiasm for natural history.

However, at the Natural History Society’s AGM in December of that year, she was elected as one of the Society’s Honorary Secretaries – the first woman in the Society’s then-119-year history to hold this office.

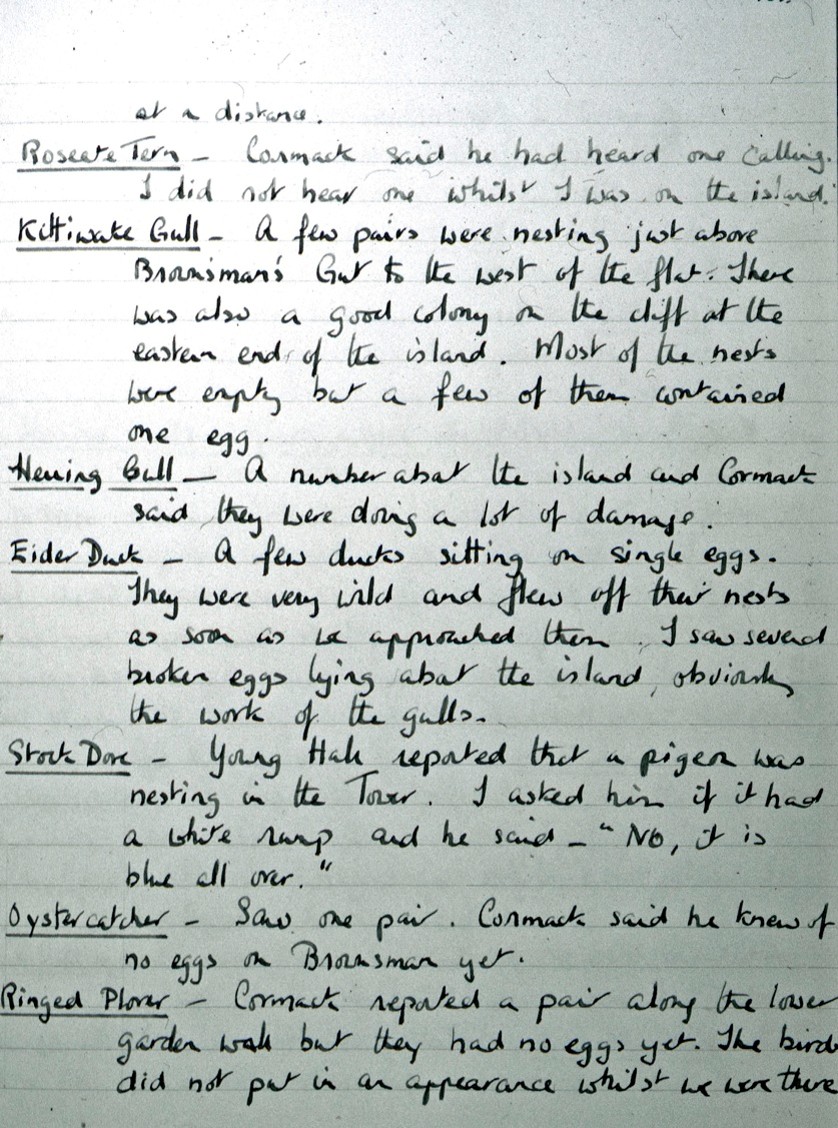

After Tom’s death, Grace set to work transcribing both his notes on natural history and his visits to the Farnes into six diaries. She continued these with her own notes concerning her visits to the Farne Islands for the rest of her life, producing 22 volumes which are now in the NHSN’s North East Nature Archive.

Diaries can often can give a good idea of a someone’s personality: Goddard’s do, but sadly not Grace’s. She is very reticent regarding her feelings, and only at the end of volume 21, late in life, does she actually admit to feeling unwell and to have difficulties getting into and out of the boat to the Farnes. I have had to rely on other people for her character, especially Margaret Patterson who served as her secretary for many years.

Grace’s closest friends were her cousin Grace, and a school friend Biddy who was a cook at an upmarket hotel in Burford, and where Grace often spent her holidays. Incidentally Grace herself was an excellent cook.

To gain Grace’s trust and friendship seems to have taken some time; she was highly intelligent and in possession of a very strong personality and strong opinions. In fact, without these character traits she may never have been as respected as she was, in what was then very much a man’s world.

She was a perfectionist, who demanded the highest standards both of herself and everyone working for her, and could be critical of those she thought had failed her. She edited all the society’s publications, and when visiting the publishers she would even take a ruler to check the spacing between the lines. It had to look just right!

However, she was also kind and considerate to her staff, introducing Margaret’s children to the Farnes and inviting Margaret to accompany her there on a number of occasions, both in summer to ring birds, and winter to tag the seals. On one occasion in winter, when going to the islands, Margaret was handed a sprayer and asked to pump it up. Suddenly, after a while with nothing happening, a red dye shot out of the nozzle and covered Grace all over. Grace was not amused, especially as she was wearing a new jacket given her by the RNLI.

Behind her stern façade, she was very generous to her friends: when a friend’s car broke down Grace insisted that he borrow hers until he was able to purchase a new one. She referred to herself as “a demon driver” and apparently succeeded in turning her car over at least once! She seems to have both loved and connected with animals, and enjoyed having Margaret’s dog in the office.

As the Honorary Secretary of the Society she was responsible for administering all its affairs, and for 38 years she carried out unpaid work in managing all the daily work of the Society; she was an excellent organizer and administrator, and worked with an extreme devotion, spending several hours each week day in the office: all her editing, writing and research was done in the evenings and weekends at home.

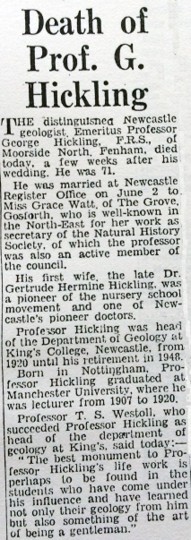

One of her first tasks after her appointment was to organize the library, which was in an appalling condition. She was helped in this by Professor George Hickling, whom she married in 1954. Tragically, he died only a few weeks later: following this blow, Grace became even more dedicated to the Society and her work on the Farne Islands.

At some stage she set about editing the Society’s Transactions, bringing it up to her usual high standards and meticulous attention to detail. While the majority of authors were, on reflection, grateful to her, there could be friction as her particularly high standard did not please everyone. Her overriding concern was always the reputation of the Society, and nothing could divert her from this goal.

It is particularly fitting and pleasing that her work was honoured during her lifetime. In the birthday honours of 1974, she was awarded the MBE for her services as Secretary of the Northumberland Natural History Society.

Grace Hickling and the Farnes

Grace is perhaps most remembered today for her work on the Farne Islands. In 1946, she was elected to the Farne Islands Local Committee of the National Trust, now called the Farne Islands Advisory Committee.

Although she was not the first woman to work on the Farnes, she was certainly the first to work with the grey seals. On her very first visit with Goddard in 1940 she was captivated by them, later writing of the experience: “Birds were everywhere, but the sight of seals, bobbing up out of the water to inspect these alien visitors…was one which I will never forget. …Even the scientific name for seals – pinnepedia, or ‘wing-footed’ – suggests a mysterious animal, and seals are indeed fascinating creatures.”

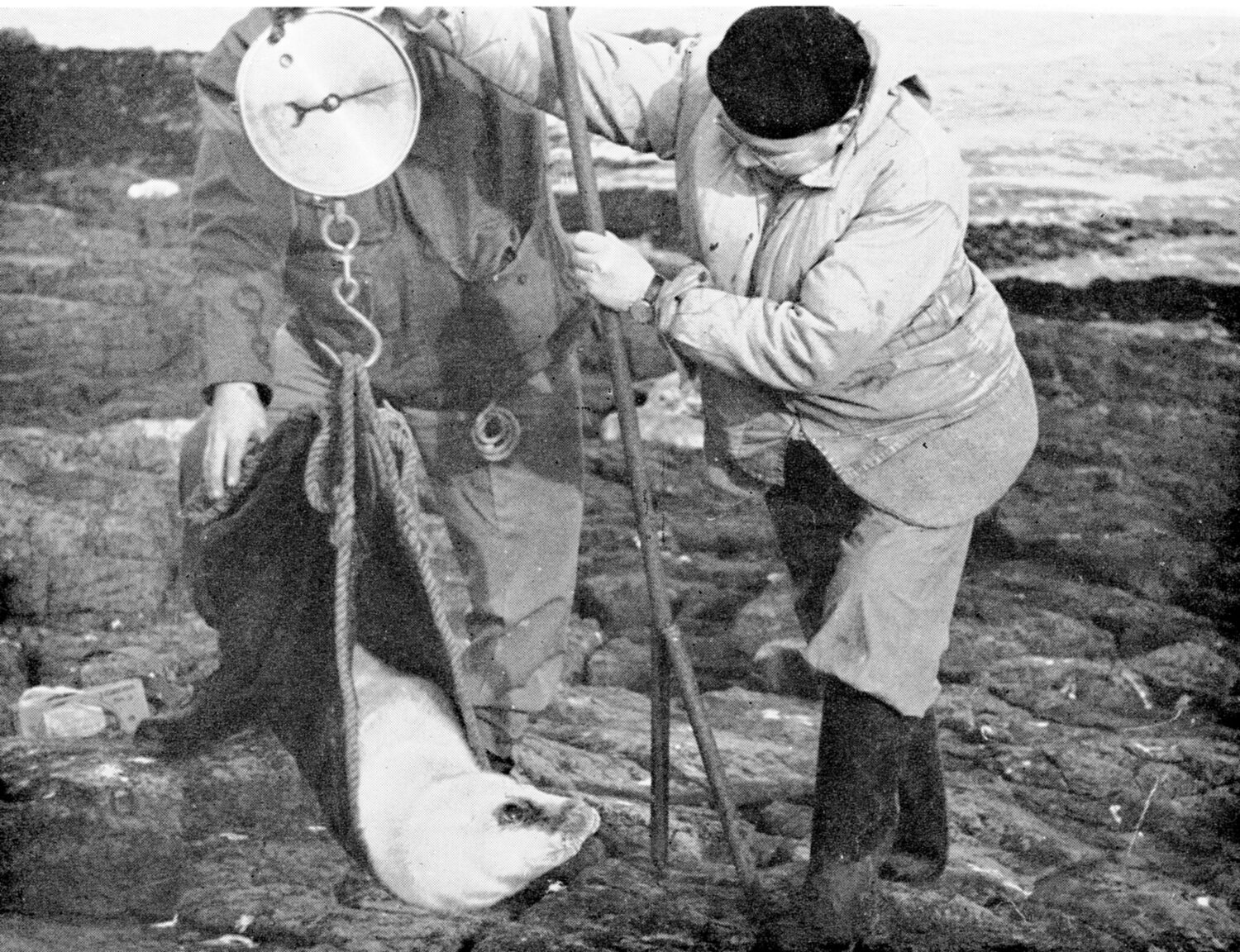

In 1949 Grace and Ian Telfer, an NHSN member, decided to mark seals in an attempt to follow their movements. Though grey seals are resident on the Farnes, nothing was known about them outside the breeding season. The first seals were tagged in 1951, and within fifteen days the first marked seal was recovered in Norway. This was ground breaking research as no one had realised how far the Grey Seals were travelling.

In addition, she counted, measured and weighed the seals and continued these measurements each winter until she died, producing a vast amount of data, which was published by the NHSN.

In time, physical tagging was replaced by vegetable dyes in a variety of colours. First the first few years Grace used a walking stick to apply the dye, and the NHSN still has it in the archive. Today, seals are counted using drones.

In the late fifties and early sixties, under pressure from the fishermen of the North East coast, several culls of seals were undertaken. Grace was heavily involved in the decision-making around the issue, and though she had opposed the culls she consented to act as an observer. During the second cull, in December 1958, the people employed to carry out the shooting were concerned about the animals suffering, unlike those who participated in the earlier culls. Here is Grace’s diary entry for Wednesday 3 December:

First day of the Ministry of Agriculture killing parties and a dreadful one which none of us will ever forget. The dreadful thing is the difficulty in killing the calves outright. …This is not something that should occur in a sanctuary. Two of the boatmen commented after taking part, that they wished it had been the Berwick fishermen, not the seals who were suffering in this way.

Later on, Grace helped to draw up a plan to reduce the population to about 1000 cows, as overpopulation was causing problems for the seals themselves as well as other wildlife – puffins, for example, were becoming threatened by the sheer volume of seals crushing their burrows. This time the cull was done by shooting, which was thought more humane; in this case as in the previous one, however, Grace’s involvement made her the target of hate mail.

Though Grace was the first woman to work with the seals, she was not the first to work on the Farnes; this was the bird ringer Catharine Hodgkin. Grace had been taught to ring by Tom Russell Goddard, who in turn had been taught by Hodgkin.

Under Grace, a total of around 187,000 birds of 48 different species were ringed from 1949 until her death in 1986, many of these personally. She was always excited to hear of ‘her birds’ being recovered from all corners of the world, especially those that had travelled a long way.

In 1982 an immature Arctic Tern was found within one hundred days of ringing which had travelled over 17,000 km, while in 1961 one was killed against a Japanese whaling vessel in the Southern Ocean only five months after being ringed on Brownsman in July – the first Antarctic recovery for a Farne Island Tern.

In 1959 Grace was awarded the Silver Medal of the RSPB for her services to bird protection.

Through her two books, The Farne Islands: Their History and Wildlife (1951) and Grey Seals and the Farne Islands (1962), Grace brought the Farnes to wider attention as a treasure of natural and human heritage. At the same time, she was instrumental in setting up the permanent study centre, and helping to establish the Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve in September 1964. Today this reserve is an important breeding site for Little Terns, an endangered species.

While doing all this and running the NHSN, Grace was instrumental in many other ventures: she played a leading role in the setting up of the original Northumberland and Durham Naturalists’ Trust (now the Northumberland Wildlife Trust), and served on its steering committee and its Council. At one time she even became Councillor Mrs. Hickling!

On May 3rd 1986 while on the Farne Islands, Grace fell down a bank and rolled. We do not know exactly where, but perhaps it was Cottage Cliff on Brownsman, a particularly steep area. She said nothing but suffered from headaches for a couple of weeks.

She never recovered from this fall, and though she continued visiting the Farnes, she found it increasingly difficult, especially getting into and out of the boats. On the evening of December 30, while sitting alone at home, she died and was not discovered until the next day.

As she had no living relatives the Society offered to help with the funeral arrangements. The service was at the West Road Crematorium and members of the congregation were invited back to the Council Room in the Museum, which was closed until 1pm as a mark of respect.

In a touching gesture, Robert, one of the porters, illegally raised the Union Flag to half-mast.

In accordance with her wishes, her ashes were scattered in St Cuthbert’s Cove Inner Farne, on March 20th, 1987 – the 1300th anniversary of St Cuthbert’s death.

Then in spring 1988 a bronze plaque designed by James Alder, was placed on a rock face in St Cuthbert’s Cove. Today it is on the wall of the visitor centre.

The inscription on this plaque reads “Grace Hickling 1908-1986: Protector of Northumbrian Wildlife”. When we consider all her work on the Farnes, the Natural History Society of Northumbria, the Northumberland Wildlife Trust and Lindisfarne NNR as well as numerous other committees, I think no one could deserve this epitaph more than Grace Hickling.