World Mental Health Day is 10th October every year. By happy coincidence, I picked up a new acquisition from the Natural History Society of Northumbria’s collection at the Great North Museum: Hancock’s Library that week. I then noticed further coincidences when leafing through the latest RSPB magazine, Nature’s Home, and the Observer newspaper’s magazine section that weekend. Both carried items featuring the health benefits, mental and physical, of bird watching. David Lindo, the urban birder, described the onset of depression some years ago and the medical advice to focus on what he enjoyed doing. A young birder told how she did not find meditation worked for her until she discovered being outdoors watching birds was her meditative space and activity.

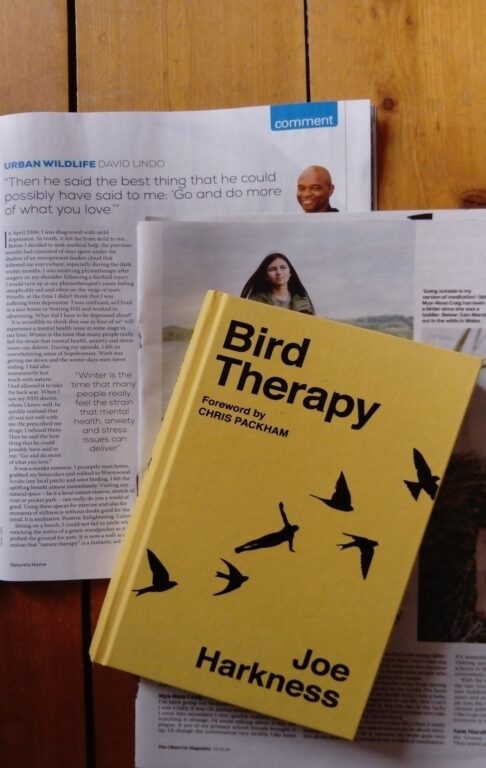

Joe Harkness’s book (Unbound is the first crowd-funded publisher) is a very personal account of his journey through mental ill-health and the role that bird watching played in his recovery. It involved the rediscovery of the value of being active outdoors and focusing on the absorbing business of watching birds specifically and the natural world in general. He is very open about the triggers for his mental ill-health which had to do with family relationships and a stressful job. The description of his problems leads to the account of how he was helped to become aware of ways of managing his health. After self-medicating with alcohol, as is not uncommon, he was introduced to the 5 a day programme promoting positive mental health. This advocates that we connect (with self, others and our environment),are active (in a variety of ordinary ways), take notice (of what is going on around us and savour the moment), keep learning (new skills and ideas) and give (ourselves voluntarily for the common good).

Harkness also experienced the eight-session programme of mindfulness-based stress reduction developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn Mindfulness is a modern formulation of ancient wisdom which promotes the practice of paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally. This involves, amongst other things, focusing on the breath and returning to it whenever and wherever the mind wanders, as it will. It can also involve focusing on sounds, both near and far, and Harkness relates this to bird song. It was good to see this practical application of this therapeutic exercise (I used to practise and teach, in NHS mental health services, both this programme and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression). He describes also the value of adopting a “patch” and going out in all weathers throughout the year, sometimes alone but often with a birding companion. Each chapter finishes a list of helpful hints borne out of his own experience. This approach changed his relationship to his mental pain and freed him from previous preoccupations and obsessions. His heightened awareness of himself and the natural world was healing.

The healing power of the natural environment is yet another argument for humankind to cease its sick destruction. Ecotherapy is recognised increasingly as effective with a growing body of evidence, including from neuroscience, of its benefits. It is implicit in J A Baker’s The Peregrine and more explicit in Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk and Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun. At the moment none of these titles feature in this library. Interestingly the latter two are in the Medical Literature section of the Walton Library of Newcastle University Medical School. I do not know if this positive and readable book will make it there but it is available now in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library on the second floor!

Bird Therapy, by Joe Harkness. 2019. Unbound, 290 pp. ISBN 978-1-78352-772-4 (hardback), ISBN 978-1-78352-774-8 (ebook) £14.99

By a library volunteer