Heritage Researcher Mel Tuckett and volunteer Alan Hart introduce one of the artistic highlights of the North East Nature Archive

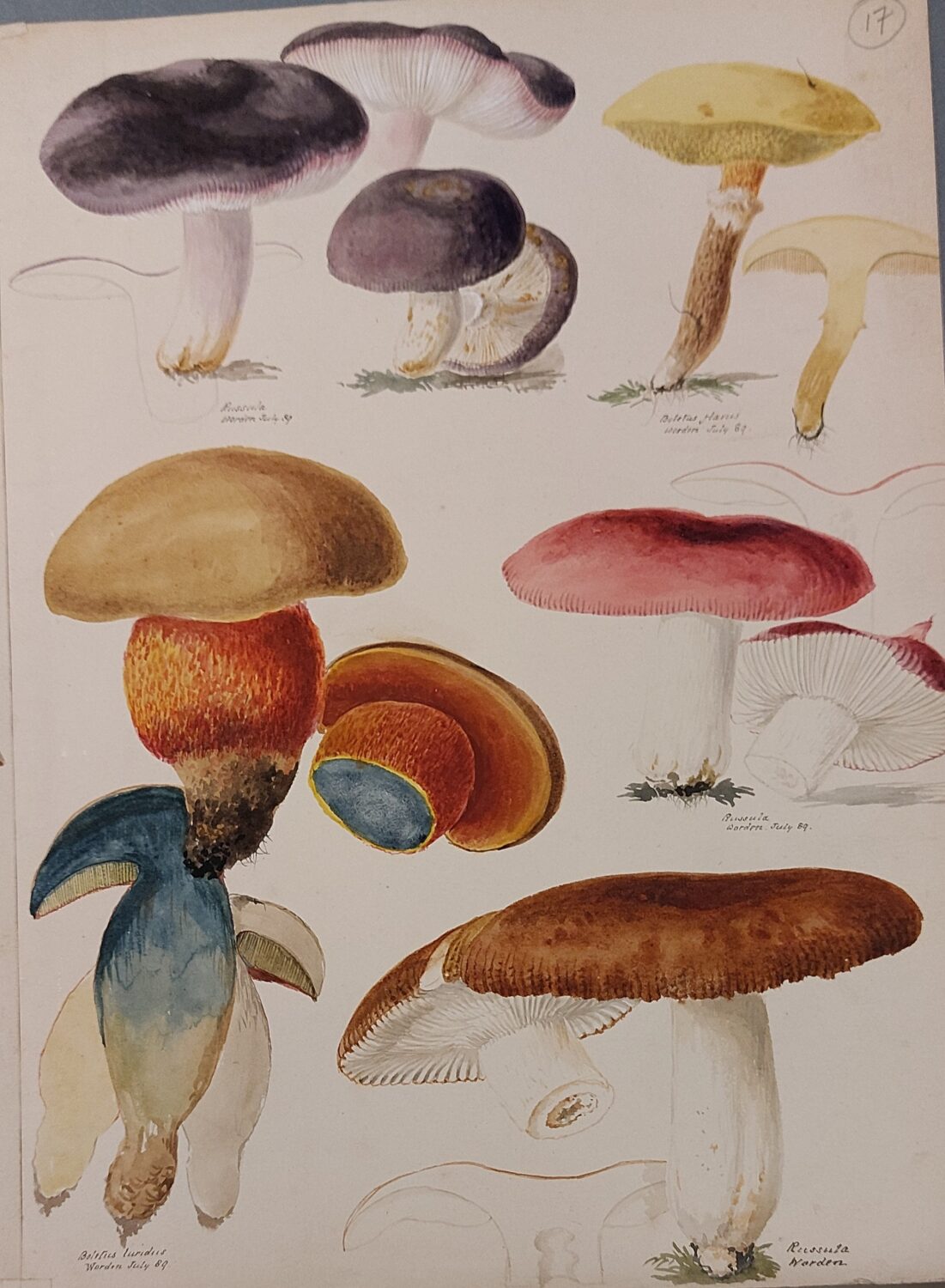

In the autumn, fungi are a beautiful, yet curious aspect of a nature walk. They constantly surprise us with their many different forms, colours and habitats. Did you know that fungi are classified as neither plants nor animals, but have their own kingdom? They have a unique biology and life-cycle that sets them apart, and which seems to challenge our understanding of how life usually takes place. The fungi we see in autumn have spent most of their time underground or inside their hosts, and the mushrooms, brackets and toadstools have appeared to spread their spores. Maybe it is this hidden and mysterious lifecycle that makes them seem otherworldly and secretive? To some people fungi feel almost unsettling and not to be trusted. It’s perhaps not surprising that they have associations with poison, witchcraft and Halloween. It is also not surprising then that fungi are often a subject of art and study. Amongst the treasures of the North East Nature Archive, we have a beautiful example of this in the fungi paintings of Sarah Dickson.

Sarah Dickson was born on 30 August 1821 and died on 16 October 1896. Yet beyond these dates, we have no information about her. Archive volunteer Alan Hart has looked to the paintings and their time of creation to give us some insight into this hidden life. He highlights that Dickson seems to have been active between 1855 and 1894, a time in the Victorian era when women were gradually establishing themselves as artists capable of earning a living from their work. Painting and drawing, particularly flowers and landscapes was an essential part of being an accomplished and marriageable middle-class lady at this time. Women were thus able to become more widely recognised for their artistic skills. However, these skills could also be turned to other uses, as close observation through drawings and paintings of wildlife was a key aspect of nature study in this period. This development may have therefore helped women like Sarah Dickson to expand their experience and access the scientific world.

A clue within the paintings suggests that Dickson may have sought to follow this path. Alan notes that the fungi are classified to species level, and have locations recorded. This makes it possible that Sarah’s motives for painting might have included a scientific interest in botany. In her day, it was relatively unusual and sometimes difficult for women to attend university and become scientists in the modern sense, but nonetheless women have played an important part in the establishment of botany as a science. Perhaps she had private means or an obliging family who supported her art and science?

Thus, it is most likely that we know so little of Sarah Dickson’s life and art because of the times in which she was working. What we do know is that she was a prolific artist. Our archive contains about seventy of her fungi paintings, as well as 250 paintings of flowering plants. We have found evidence of a further 400 paintings which may be in private hands. However, if anyone has any information of where these might be or can give us any more insight into Sarah Dickson, it would be great to hear from you. We would love to give her life and work the recognition we feel it deserves.

As you can see, Sarah Dickson’s paintings burst with life and the detail is stunning. The care she takes to convey the rich colours and varied forms surely tells us that Dickson was passionate about fungi and wanted everyone to share this excitement. So why not come to one of our Treasure of the Archive events to see some of Dickson’s work up close? These sessions offer you an opportunity to come to the Great North Museum; Hancock to view some of our most valued and inspiring books, pictures and journals. Next date to be announced soon.

We really hope these fascinating lifeforms and their beautiful depictions by Sarah Dickson will inspire you to get out and enjoy some of your local nature.