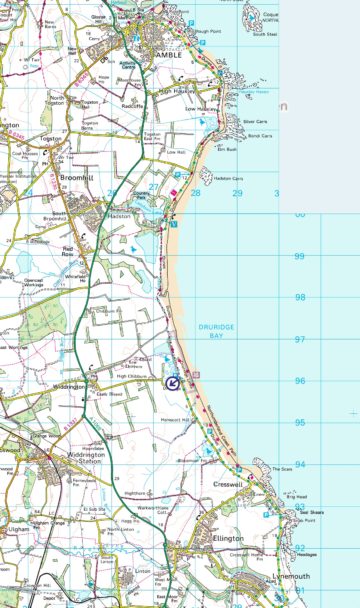

The sweep of Druridge Bay itself, some eight kilometres of sandy littoral a little to the south of Amble in Northumberland, is part of a coastline between the estuary of the Coquet and the more modest outflow of the Lyne about fourteen kilometres back towards the port of Blyth. Contained in that stretch, which does not form part of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty to the north, is a rich group of ecosystems including, in addition to the beaches, fresh and saltwater ponds and pools, sedimentary rock outcrops, peat, dunes, agricultural land and mixed woodland. There is substantial human habitation in Amble (population around 6000) and in Cresswell / Ellington (around 3000) which, through fishing and historical mining and quarrying, have also influenced the landscape and biodiversity.

A major thrust of any diary style writing about the natural history of this area will be a focus on the changes in the geology, botany, avian and marine life, reflecting the very frequent alterations of light, wind, wave-power and weather. If you simply look at one section of beach, for example, the lines of the sand, the nature of the sand, the contents of material on the sand surface can be revised daily by tide action. This is not a cycle but an open-ended process where perfectly smooth firm sandbars are built, leaving flowing channels behind them throughout the low-tide period, and then are washed away again. The beach can slope evenly across the intertidal zone or descend in a series of ledges. In the late winter of 2017-18, the whole beach was lowered and new sets of Second World War tank trap concrete blocks were exposed which by July were barely visible again. By the Druridge hamlet on consecutive days there can be a ‘naked’ beach, consisting only of a variation of smooth sands of different saturations and varying shades of ochre and cadmium, a patterned sandscape where tidal ripples have cut long ridge and furrow lines and a beach, spread with kelp, fragmented pebbles and coal dust or marine life such as jellyfish (which usually appear for a day and are then gone).

For the summer months, one aspect of those changes is found in the plant growth within the dunes. After a winter when the height of all vegetation falls away to near ground level and the low hawthorn bushes lose their impact as they become skeletal the first spring growth was in the resurgence of the marram grass on the sections of dunes closest to the sea; it had settled back to the largely dry straw texture and colour rather than showing its summer fresher green, but as May progressed into June and temperatures rose, the new sharp fronds brought back the wash of greenness which characterises the dune landscape as a whole. The plants come and go in waves. At first, there is a prevalence of white clover, birds-foot trefoil and then a rich abundance of bloody cranes-bill, the ‘Northumberland flower’. After an early flush of cow parsley, other umbellifers develop both low to the ground and much higher through June and into August. Sprinkled harebells and localised clumps of different forms of willowherb then catch the eye and the grasses continue to grow, especially when there is a period of rain and following sunshine. This growth obscures the dune paths that in winter were clear trails but by August have become shoe soaking routes between dune peaks.

In the bay, the summer has been marked by the attention-grabbing flight of terns and gannets with their different wing movements and spectacular dives into the water. Sanderlings that disappeared for the breeding season reappeared in small groups at the beginning of August and provided a strong contrast to the distant fishing seabirds with their bursting runs and continuous efficient feeding just ahead of walking humans besides the incoming waves.

Future posts will focus more closely on individual aspects of the Bay.

By Philip Hood