Ian Bower pursues a largely-forgotten artist and science fiction visionary through the North East Nature Archive

The North East Nature Archive contains a rich collection of historical botanical books, many containing impressive colour illustrations. One of these works is a series of titles by the now largely forgotten author and illustrator Jane Loudon (1807-1858). She was a fascinating character and provides an important example of how women contributed to the development of writing about horticulture and the natural world. She published a celebrated series of innovative books that helped to popularise an emerging interest in gardening and horticulture among middle-class women in the mid-nineteenth century. As a young woman she was also the author of a prescient and influential science fiction novel.

Born Jane Webb in Birmingham in 1807, Loudon’s affluent family background enabled her to travel widely and gain first-hand experience of other cultures. She also mastered several languages. At the age of twenty, as a result of the need to support herself financially after the death of her parents, she anonymously published a novel titled The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century which appeared in 1827 in three volumes. The book narrates the story of the Pharaoh Cheops, a reanimated Egyptian mummy in England in the year 2126. The work is not solely a tale of gothic fiction, however. Jane’s imagined future explores inventions and ideas that are impressively prophetic. She writes of automaton surgeons and lawyers, of smokeless cities, steam digging-machines, steam cannons, and even more surprisingly, “a patent steam coffee-machine, by which coffee was roasted, ground, made, and poured out with boiling milk and sugar, all in the short space of five minutes.” She also writes of a matriarchal society years before Queen Victoria was on the throne.

Her future husband, John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843) was a noted Scottish botanist, garden designer and author. He was the founding editor of The Gardeners’ Magazine, and had read and favourably reviewed The Mummy. He was intrigued by the fantastical elements of the story and the futuristic agricultural inventions it contained (particularly the idea of a mechanised milking machine), and requested a meeting with the author, making the assumption that this would be a man as the book had been published anonymously. To his surprise he met instead with Jane, and was soon smitten. He successfully proposed shortly afterwards and they were married in 1830.

From a position of having no significant background in gardening or botany, Jane concentrated on building up her knowledge of these subjects with the support of her spouse. By her early twenties she was actively assisting her much older husband in editing his publications, in particular his extensive Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1834). She also planted and maintained the gardens at their London home. As a result of these activities, she became increasingly aware of the existence of a gap in the market for easy-to-understand gardening manuals for women like herself. Many of the existing books in this area were too technical and specialised for the everyday person to enjoy reading and understand easily.

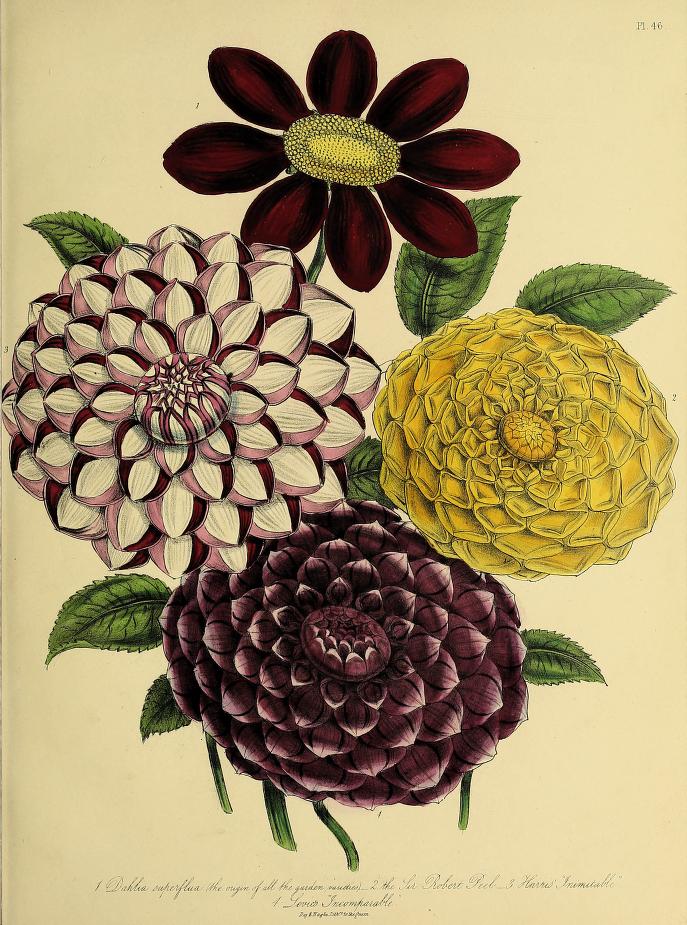

Because of financial difficulties resulting from technical problems with the publication of one of John Claudius’ books, a source of alternative family income became critical. Jane focused on making the production of pioneering, accessible illustrated gardening manuals for the enthusiastic amateur female a reality. As well as providing the text, she also became a self-taught botanical artist and was responsible for the vibrant illustrations in her works.

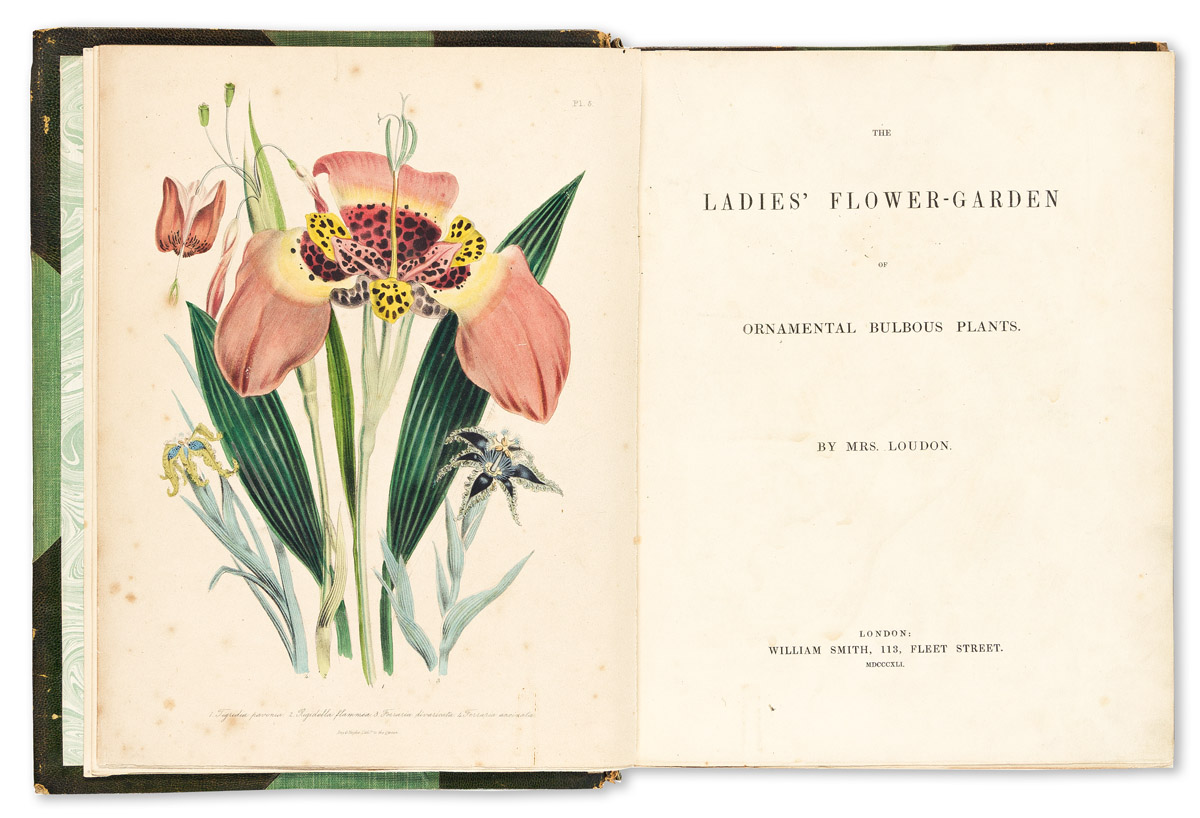

One of her most popular publications was the Ladies’ Flower-Garden series, of which the first title, The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Annuals, appeared in 1841.

Over the next few years subsequent titles included The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Bulbous Plants, The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Perennials, and The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Greenhouse Plants.

In the introduction to her first book, she outlines her aim:

“Of all kinds of flowers, the ornamental garden annuals are perhaps the most generally interesting; and the easiness of their culture renders it particularly suitable for a feminine pursuit. The pruning and training of trees, and the culture of culinary vegetables, require too much strength and manual labour; but a lady, with the assistance of a common labourer to level and prepare the ground, may turn a barren waste into a flower-garden with her own hands. Sowing the seeds of annuals, watering them, transplanting them when necessary, training the plants by tying them to little sticks as props, or by leading them over trellis-work, and cutting off the dead flowers, or gathering the seeds for the next year’s crop, are all suitable for feminine occupations; and they have the additional advantage of inducing gentle exercise in the open air.”

The books were highly successful in meeting the needs of the growing number of middle-class female readers with an interest in gardening. They sold in large quantities and ran through multiple editions. It was said at the time that Jane Loudon was to Victorian gardening what Mrs Beeton was to cookery. Women all over the country were spurred by her books into taking up gardening as a hobby.

The books provided a much-needed blend of practical and useful information about plants, as well as outlining tasks that should be undertaken in the garden. Loudon realised that the use of attractive illustrations would be critical to the success of the books. The appealing colour images that she incorporates in her books often included flowers arranged into colourful bouquets. In her later books she used the new technique of chromolithography for multicolour prints.

The Loudons came to be regarded as among the leading horticulturalists of the day, mixing in social circles with literary giants such as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray. They also travelled widely to inspect botanic gardens, in the process becoming early adopters of garden tourism.

Unfortunately, John Claudius Loudon died relatively young, and Jane’s fortunes steadily declined as she found herself single, with a young daughter to support, and in financial difficulties. She struggled on, existing on a small pension, but she died almost penniless in 1858, aged only fifty-one.

In her relatively short life, Loudon exhibited the rare ability to generate new and ground breaking ideas in totally different fields. She was tenacious, resourceful and inventive in carrying them through to fruition and subsequently establishing herself as a major figure of her day. Despite these achievements she is sadly now a largely forgotten figure. Perhaps it is now an appropriate time to celebrate her life and works.