North East Nature Archive Volunteer, Alan Hart, discovers intriguing traces of a world-famous inventor

Earlier this year I was asked, as a volunteer in the NHSN archives and library, if I would like to transcribe some bundles of handwritten correspondence from the late nineteenth century. Hmm… might be a bit boring, I thought, but I’m happy to give it a go. Well, I soon became disabused of that view; the past really is a different country, and the letters contain insights into the attitudes and interests of naturalists of the time. (Their handwriting was generally bad too, which slows transcription up a bit.)

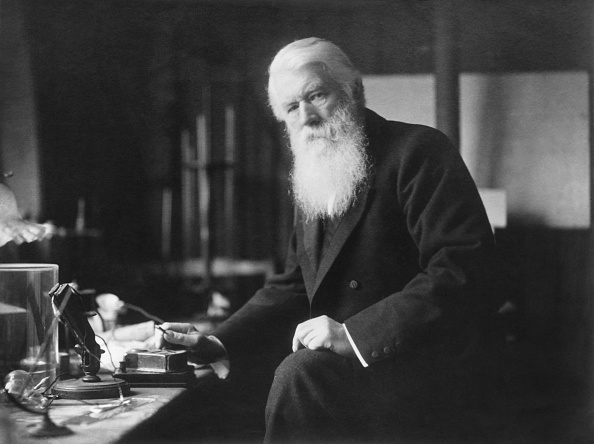

One of the bundles I transcribed contained some correspondence between the Society and one J. W. Swan about installing electric light in the Museum. Swan!? Isn’t he famous in Newcastle? Didn’t he have something to do with the invention of the electric light bulb? Yes, he did. From the 1850s onwards, Sir Joseph Swan (1828-1914) worked, initially at Low Fell in Gateshead, on developing a lamp which would throw out light from the incandescence of a carbon filament when an electrical current was passed through it. By 3 February 1879, he was able to demonstrate a functional lamp to a public meeting of 700 people at the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne. The building was lit by gas, but on Swan’s turning off the gas lamps, it was immediately illuminated by electric light from his incandescent bulbs. A further public demonstration to 500 people in the Gateshead Town Hall took place on 12th March,1879. By 1881, the Swan Electric Light Company had been formed to manufacture bulbs of Swan’s design.

Swan did not work in isolation. He was aware of international attempts to develop electric lighting, for example the use of arc lamps to illuminate streets in Paris. His lamps were dependent on other technologies and skills being available: glass-blowing to make the bulbs housing the filaments, vacuum pumps to evacuate the bulbs, and a suitable supply of electricity (in the early days, direct current from batteries or dynamos). Most famously, Swan had learnt by 1880 that Thomas Edison had also made an incandescent lamp in the USA. Swan and Edison went on in 1882 to jointly form a company, the Edison and Swan United Electric Light Company or Ediswan, to manufacture incandescent bulbs. Between them, Swan and Edison had invented a way of generating electric light by incandescence from filaments enclosed in sealed bulbs.

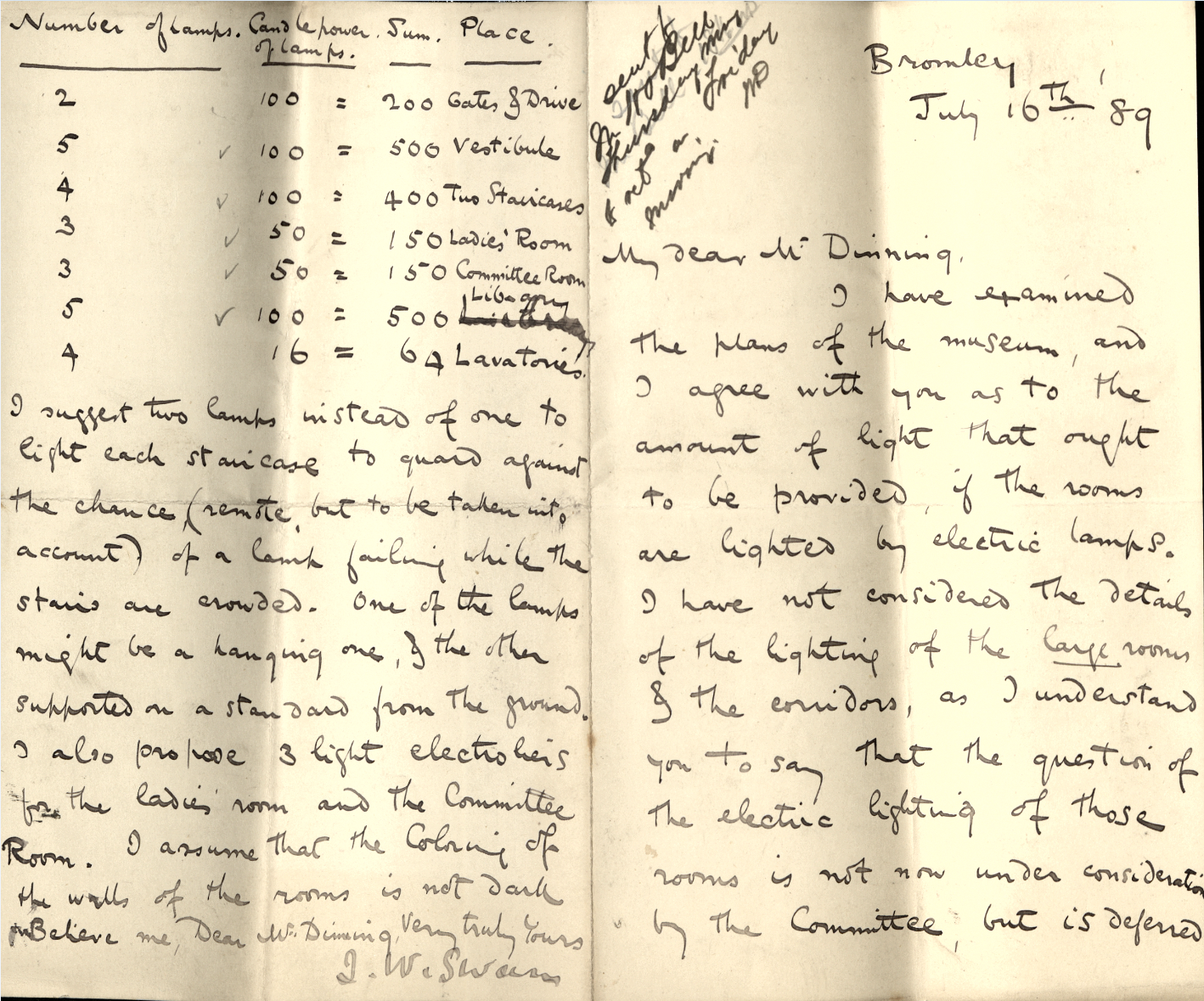

So what are the four letters from Swan to the Natural History Society about? They are about plans to install electric light in the Museum, presumably replacing gas lighting. After the initial demonstrations of electric lighting in the early 1880s, there was continuous improvement of the lamps and associated circuitry, so the Museum administration may have felt it was wise to wait a few years for teething problems to be ironed out – or for funds to become available – before installing the new mode of lighting. The first letter (4 July, 1889) contains some illegible words but is probably to William Dinning, the NHSN’s Honorary Secretary. In it Swan offers advice, a share of expenses and supply of the lamps, should the project of lighting the museum with electricity proceed. He asks that Hancock be apprised of his warm support. The second letter (15 July, 1889) is brief, and is to reassure Mr. Dinning that his support is available for either a partial or complete change in the means of lighting the museum. The third letter (16 July, 1889) contains details of Swan’s suggestions for the project, and is reproduced here.

My dear Mr. Dinning,

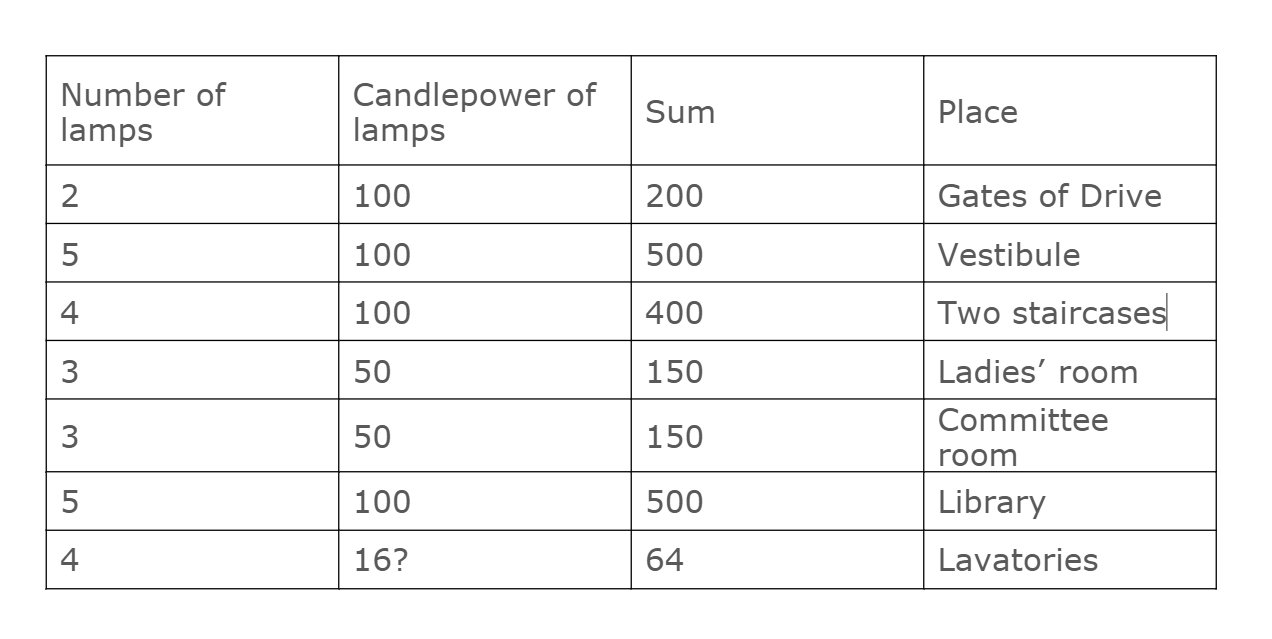

I have examined the plans of the museum, and I agree with you as to the amount of light that ought to be provided if the rooms are lighted with electric lamps. I have not considered the details of the lighting of the large rooms & the corridors, as I understand you to say that the question of the electric lighting of those rooms is not now under consideration by the Committee, but is deferred until there is prospect of the funds for this large piece of work being obtained. I see the amount of light required for the entire lighting of the museum is about eight thousand, four hundred candlepower. As probably the Committee do not entertain the idea of generating the electric current, but are expecting to be supplied from outside by one of the Electric Light Companies, it is not so important that the power to produce it should be economised as otherwise it would have been. I take it that except perhaps for a temporary purpose such as the meeting of the British Association, there is no question as to the use of any but incandescent lamps. For permanent lighting I think arc lamps are inadmissible, both on the grounds of safety from fire and purity of the air. I see you have dotted the places, where there should be lamps for lighting the rooms it is now thought of lighting. I think a lamp or lamps at each of the places you have marked will produce a good effect. If the lamps are of the following sizes and arranged as indicated I think the light will be brilliant, as it ought to be.

I suggest two lamps instead of one to light each staircase to guard against the chance (remote, but to be taken into account) of a lamp failing while the stairs are crowded. One of the lamps might be a hanging one, & the other supported on a standard from the ground. I also propose 3 electroliers for the ladies’ room and the Committee room. I assume that the coloring of the walls of the rooms is not dark.

Believe me,

Dear Mr Dinning, Very truly yours,

L. W. Swan.

In the fourth letter (July 23rd, 1889) Swan rectifies a misunderstanding he feels he may have caused, and makes clear his intention to pay for permanent installation of lamps in the museum.

On the 14th October, 1891, at the Annual General Meeting of the NHSN, the Committee was able to report “with gratification, that during the past year the Museum has been permanently fitted with the Electric Light … Mr. J. W. Swan most kindly presented the Society with the whole of the electric lamps required for the Entrance Hall, Ladies Room, Committee Room, two Stair-cases and the Library.”

How brightly did the new technology light the museum? Five hundred candlepower in the vestibule might have provided about 6500 lumens, the equivalent of about four modern 100-Watt incandescent bulbs. If these conversions from candlepower to lumens are correct then they suggest that the electric lighting installed in the museum might have seemed quite dim to modern eyes, accustomed as we are now to inexpensive, bright lighting based on LEDs. The ability to turn on the electric light instantly, without the odour, dangers and relatively dim lighting of gas lamps, must have seemed rather wonderful.

Swan was one of the large group of inventors of nineteenth and early twentieth centuries whose inventions – inexpensive and readily available lighting, railways, the internal combustion engine, telegraphy, and more – changed the world. The Swan letters are a fascinating and tangible record of the interaction between one these great inventors and the Society.

Works consulted

Clouth, D., A Pictorial Account of a North Eastern Scientist’s Life and Work, (1978: Department of Education, Gateshead Metropolitan Borough Council)

Swan, M. E. & Swan, K. R, Sir Joseph Wilson Swan: inventor and scientist (1968: Oriel Press Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyne)