In this blog, North East Nature Archive volunteer Mel shares her research into the history of NHSN’s approach to engagement and outreach with the wider community.

On recently becoming a volunteer with NHSN, I was really inspired by how it sees itself as a welcoming community, open to all for enjoyment and study. For me, NHSN’s new project ‘Nature’s Cure in Time of Need’ sums up this commitment as it will engage with the widest community, seeking out the experiences of younger people, those with disabilities and people from a range of cultural backgrounds. It aims to hear and document their voices, exploring diverse encounters with nature and broadening the range of perspectives found within the archive.

Yet the project also prompted me to look back through NHSN’s archives to trace how the NHSN community evolved in its first hundred years. It began as an elite, a closed study group set up by wealthy men of science. Yet by gradually including women, children and people with disabilities, it grew into the welcoming community it is proud to be today.

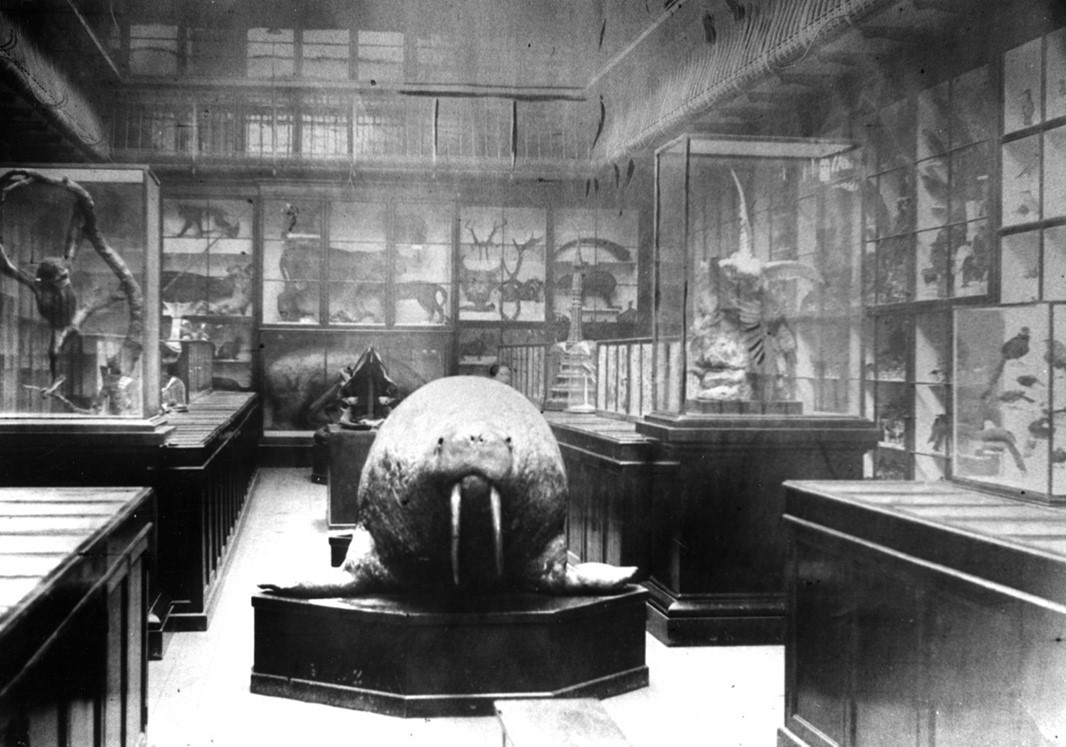

At its beginning in 1829, the organisation which became NHSN was a scientific community, a group male landowners, professionals and academics who focussed upon each other’s need for a greater understanding of nature. Following in the footsteps of those such as Carl Linneus (1707-1778) these men wanted to categorise, collect and control nature. The main method of study was to shoot, dissect and preserve. The collection at the Great North Museum; Hancock began as a record of these methods.

Women’s influence within NHSN gradually increased and evolved. They began to work in the Museum in roles deemed appropriate such as cleaning, typing and working with flowers and shells. The first female employee was Miss T. Conradi who began in 1904 and who was given the work of remounting and re-labelling the shell collection. However, as early as 1905, in an unusual all female event, the prestigious Evening Talk was presented by two women. Dr Ethel Williams chaired the presentation of “The Northumbrian Coast” by Miss E. Hollis. Women were now established as key members of the Society’s community. For further fascinating detail on these developments, go to Maureen Flisher’s recent blog on the work of Gladys Muriel Scott.

To draw children into this widening community, NHSN set up a programme of educational opportunities. As early as 1836, children’s charity schools were invited to the Museum and school visits have been encouraged ever since. In 1888, talks began on Saturday mornings and 900 children came to the first one.

Yet as early as 1831, NHSN understood that it should work towards “lifting the veil” that hid scientific knowledge from its widest audience. As stated by President Joshua Alder, the Society must reach out to “scientific strangers” to expand the understanding of nature. In 1847, women were permitted to become honorary members, but only if they were distinguished by their “attainments in the study of Natural History.” This was not easy to achieve as at this time, women’s roles were mostly in the home and education limited.

However, the work of scientists such as Charles Darwin (1809-1882) changed the emphasis of nature study which in turn helped women. He argued that observation in the field could expand knowledge of the interrelationship between aspects of nature. In 1847, as an offshoot of NHSN, The Field Study Group was formed, and this opened up greater opportunities for women who began to attend with their husbands and fathers.

In 1902, a series of Christmas lectures took place with the use of the ‘magic lantern.’ This was an early type of slide projector in which images were placed on glass and lit from behind. These talks began the inspiration for the Society’s Lantern Fund which continues to provide all children with chances to access nature.

Yet perhaps NHSN’s most innovative early move was to include those with disabilities in this expanding community. In 1897, the House Governor at the Royal Victoria School for the Blind was given “a small collection of duplicate Birds and two or three Quadrupeds” to use with his students. The aim was to enable them to handle and experience the form of nature in ways not available elsewhere.

In 1875, NHSN President Rev. J.E. Leefe recognised that “Nature is so vast a domain that there is open to everyone a field of independent study, rich in results, and inviting us everywhere to enter and enjoy.” Looking back through the North East Nature Archive, it is fascinating to see how NHSN began to extend this invitation to an ever-widening community. I look forward to seeing how the Nature’s Cure project continues this welcome and ensures that everyone has a chance to enter and enjoy the richness of nature.