In the first in a new series, Charlotte Rankin explores how you can make the most of your sightings through wildlife recording.

Across the UK, over 4.5 million wildlife records are generated each year by tens of thousands of volunteer recorders. These records underpin much of our understanding of the status of wildlife in the UK, enabling conservationists and researchers to monitor and protect wildlife.

Biological, or wildlife, recording is the process of documenting your wildlife observations. Quite simply, wildlife records pinpoint species to a specific location and point in time by a named recorder. Records inform species monitoring efforts, underpin conservation decisions and contribute to our understanding of the natural world. A biological record is generated once but used countless times.

A brief history of biological recording

There is a long tradition of biological recording. In the UK, it dates back to the mid-1600s when John Ray – known as ‘the father of recording’ – catalogued and documented species observed during his travels around Britain. During the late 18th century and 19th century, natural history societies and naturalist field clubs formed, bringing together naturalists to observe, study and record local wildlife.

In the 1950s, botanists took the lead and launched the Atlas of British Flora project in 1954 to map all plant species across the UK. Using punched cards, 1.5 million records were sorted and mapped using IT. The use of IT became integral to biological recording.

The Biological Records Centre (BRC) was established in 1964 and provides a national focus for species recording, primarily through support of national species recording schemes and societies.

Biological recording today

Today, as many as 70,000 volunteers submit records each year. This may be through involvement in focused projects or through species recording schemes, local environmental record centres and online recording websites. Many of these schemes feed into the National Biodiversity Network Atlas. The NBN Atlas is the UK’s largest collection of biodiversity data and to date, holds over 223 million wildlife records from across the UK. Wildlife recording has become an integral part of nature conservation.

Many will be aware of the value of taking part in structured citizen science and monitoring projects. But perhaps less known is the invaluable impact of general and less ‘structured’ recording via recording websites, or direct record submission to national recording schemes and local records centres. Whether recording wildlife observations in the garden, on a walk or at a nature reserve, your records make a real difference wherever you are and whatever time of year.

What makes up a wildlife record?

A wildlife record pinpoints a species to a specific location, date and recorder. When observing a species, think about the four basic components that make up this sighting: what, where, when and who.

What

The name of the species you have observed and confidently identified. When possible, it is also useful to provide an image with your record because this helps experts to confirm the species you have seen.

Where

The specific location where you found the species. This includes a location name and a grid reference that pinpoints your sighting to a specific area. The more specific you can be, the more useful the record. You do not need a GPS to generate a grid reference: there are now free phone Apps (OS Locate, for example) and Grab A Grid Reference is an excellent online tool.

When

The date (day, month and year) you observed the species.

Who

The full name of the person who observed the species. If someone helped you to identify the species, you can also add the determiner’s name.

An example of a biological record: the Tawny Mining Bee (Andrena fulva)

Additional information

Recording forms may also provide the option of including additional information such as stage of lifecycle, abundance and habitat the species was found in.

Where should I send my wildlife records?

There are a number of ways to submit your wildlife records and it can be bewildering to know where to start. It is important to find what method works best for you and where you want your records to go.

Wildlife records can be sent to national recording schemes, or vice-county recorders on behalf of these schemes, local environmental record centres or recording groups, and websites such as iRecord. Explore the different options, find what works best for you and where you would like your records to go.

There are over 80 national species recording schemes in the UK. If you are interested in a specific group, you can find out the best route to submit records for that particular group by visiting the scheme’s website.

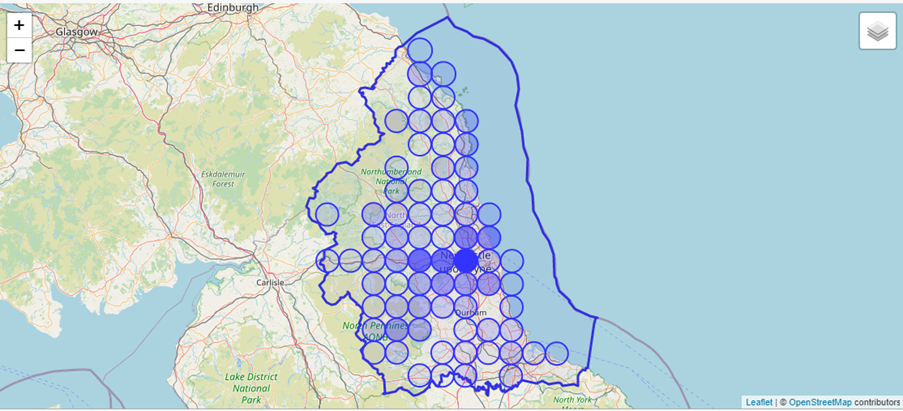

Bee records submitted to iRecord for the North East Bee Hunt

Environmental Records Information Centre North East

ERIC North East is the region’s local records centre. ERIC NE promotes wildlife recording across the region, and where possible, encouragse people to join specific groups and societies, and submit records.

iRecord

iRecord, an online recording website and App, is increasingly used by recorders across the UK. Developed by the Biological Records Centre, the aim of iRecord is to make it easier for wildlife sightings to be collated, checked by experts and made available to support monitoring and conservation efforts. These records are made available to those who need them including national recording schemes, county recorders and local records centres. Most records are also shared more widely to the National Biodiversity Network.

Another great thing about iRecord is the sheer number of groups or ‘activities’ recorders are able to join. While still ensuring your records get to where they’re needed, these provide a nice sense of community to wildlife recording. Examples include projects such as the NE Ladybird Spot or local groups such as this one for Newcastle.