Naturalist, Ryan Clark, explores the hidden world of Bryophytes in the North East, sharing the species you could find on your walks across the region.

From the mountain tops to the seashore, mosses and liverworts are found all around us. This fascinating group of plants are easy to overlook but are an essential component of the natural world. The most familiar mosses are those seen as an inconvenience in lawns, pavements cracks and gutters, but take a closer look and you will be blown away by the complexity and diversity of mosses and liverworts around you.

Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts are collectively known as bryophytes. With over 1000 species in Britain, bryophytes are a fascinating group of plants but are sadly overlooked and under-appreciated. They are an ancient and diverse group and unlike flowering plants, do not have networks of vascular structures to transport water around their tissues. This means that bryophytes are generally more diverse in wetter conditions. In periods of dry weather, they stop their metabolism to save water and can also shrivel up, waiting for rain to wake them up once again.

One of the best places to start looking for bryophytes is in a woodland. The humidity in a woodland and the complex structure can allow a diverse array of species to thrive. Branches can be adorned with liverworts entwined with cushions of mosses. Carpets of mosses reach up from the woodland floor and coat tree bases. Dead wood and rocks within woodland can also be coated with bryophytes. Some woodland bryophytes spread very slowly so are good indicators of ancient woodland.

Bryophytes in the North East

Due to the diversity of habitats in the area, over 650 bryophytes have been recorded in the North East. We are lucky to have areas of rocky crags and these can be really important for bryophytes. North-facing rocks can be especially rich, providing the complex damp microclimates that many species require. Dune slacks, such as those found on Lindisfarne, support a wide variety of uncommon and specialised mosses and liverworts. The network of fast-flowing rivers that cross the region also provide a very different habitat for these amazing plants. Due to their dependence on wet conditions, the highest diversity of bryophytes in Britain occurs as you go further north and west.

For me though, my favourite bryophyte habitat to explore is a Sphagnum bog. The north east is lucky to have some amazing bogs home to a fascinating array of invertebrates, plants, and fungi. Several our Sites of Special Scientific Interest in the region are designated for their lowland or upland bogs, some of which support over 100 bryophyte species. At the heart of the bog are the Sphagnum mosses.

Sphagnum are a group of long-lived mosses that really are a keystone species. As they grow, the bottom of the shoot breaks down and forms peat, trapping water and carbon. The world’s peatlands store twice as much carbon as the world’s forests! However, when degraded, these habitats leak carbon. Unfortunately, these amazing habitats are at risk. Many are destroyed to provide peat to the gardening industry or are seen as suitable areas for forestry. Sphagnum bogs also store water with some Sphagnum storing over 20 times their own weight in water.

Taking a closer look

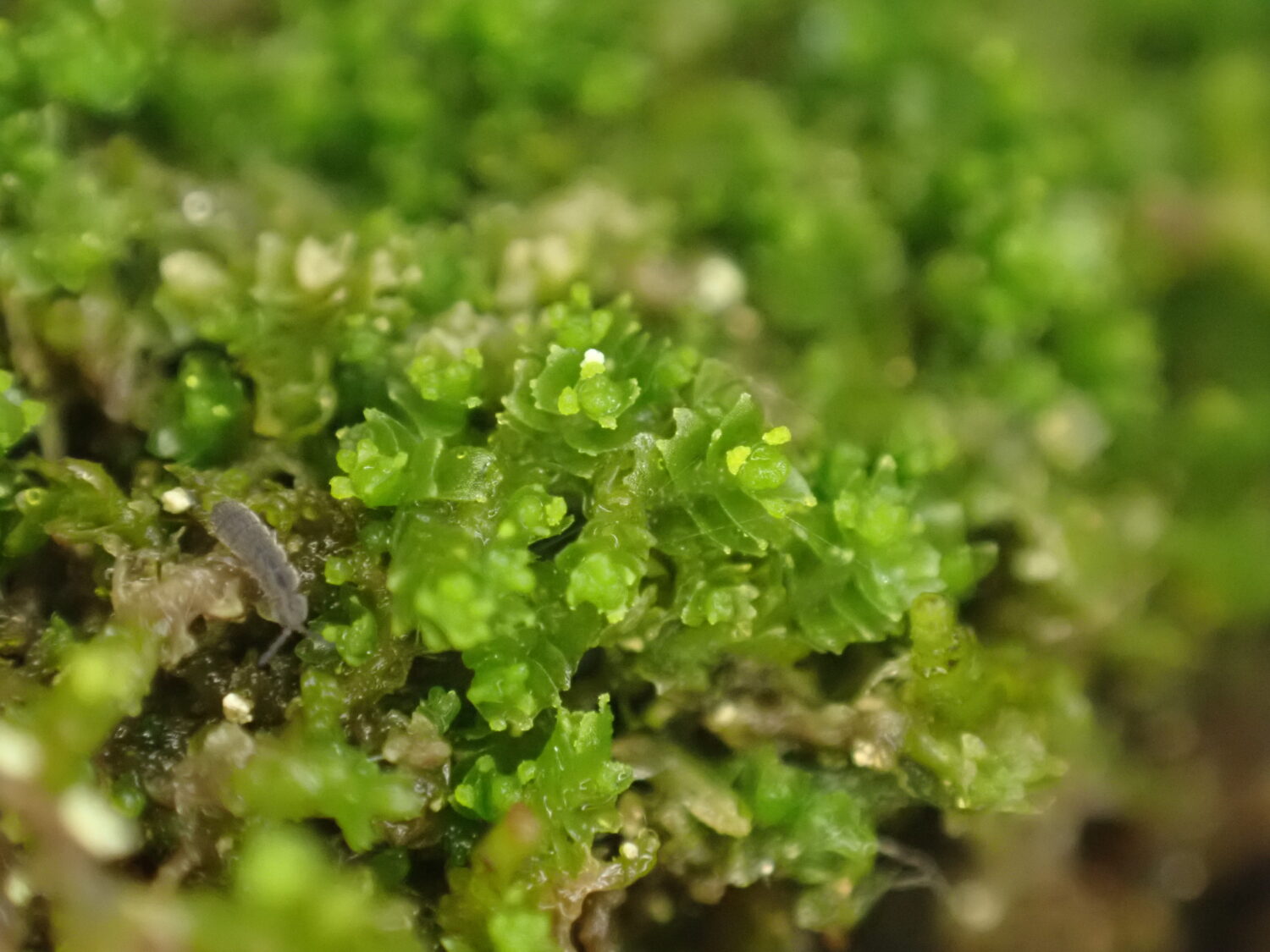

One of the reasons that bryophytes are often overlooked is that many are small. To be fully appreciated they need to be viewed up close using a magnifying glass, hand lens or camera. There is lots we still do not know about the ecology and distribution of bryophytes; anyone can make exciting discoveries. Many bryophytes can be identified in the field, but some require a closer look under the microscope to separate similar species. The best time to spot bryophytes is autumn and winter. These seasons are cooler and wetter allowing bryophytes to flourish and reproduce, making them more noticeable. This provides a welcome dose of nature when flowering plants and insects are less abundant.

If you would like to learn more about bryophytes, then the British Bryological Society website is an excellent place to learn more. NatureSpot also has a really useful gallery of bryophyte images. The gallery below is a selection of some of my favourite species I have recorded in the North East.