NHSN member, Peter Davis, shares a new North East nature book, reviewing Who Discovered the Teesdale Rarities? By Frank Horsman.

This remarkable little book builds on the author’s doctoral research from Durham University, though interestingly his PhD is not cited in the extensive Bibliography. I am always rather puzzled by books that have a question as a title, but the reason for this is simply the author’s drive and dedication to focus on this one question. As a consequence don’t pick up this book expecting an introduction to the climate, flora, geology or settlements of Teesdale, or an array of interesting plates of the ‘rarities’, or any reference to contemporary efforts to conserve them. The emphasis here is on the activities of the botanists who first explored and identified the rare plants of upper Teesdale, from the work of Ralph Johnson (1629-1695) of Brignall in North Yorkshire to the Backhouses of Darlington and York in the nineteenth century.

The author has taken a forensic approach to answer this key question, making extensive use not only of published sources, but also the herbaria, correspondence and legal documents found in a variety of scientific and cultural institutions. These include the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, the Linnean Society, the Natural History Museum, the Wellcome Collections and (more locally) resources in The Yorkshire Museum, Sunderland Museum and the Great North Museum: Hancock. Anyone who has worked with such collections will appreciate the effort it has taken not only to deal with fragile material and the transcription of difficult handwriting, but also to create a logical story from such disparate sources. What emerges from this detailed research is a much better understanding of the contributions made by many of the lesser-known botanists based in Middleton-in-Teesdale. These include the lead miner and botanist, John Binks (1766-1817), and the surgeon William Oliver (1760-1816). Horsman concludes that it was Oliver who discovered most of the Teesdale rarities and brought the flora to the attention of others. However, the Rev. John Harriman (1760-1831), curate of Eggleston Chapel, and Edward Robson, Quaker botanist of Darlington, both played important roles and feature strongly in the narrative.

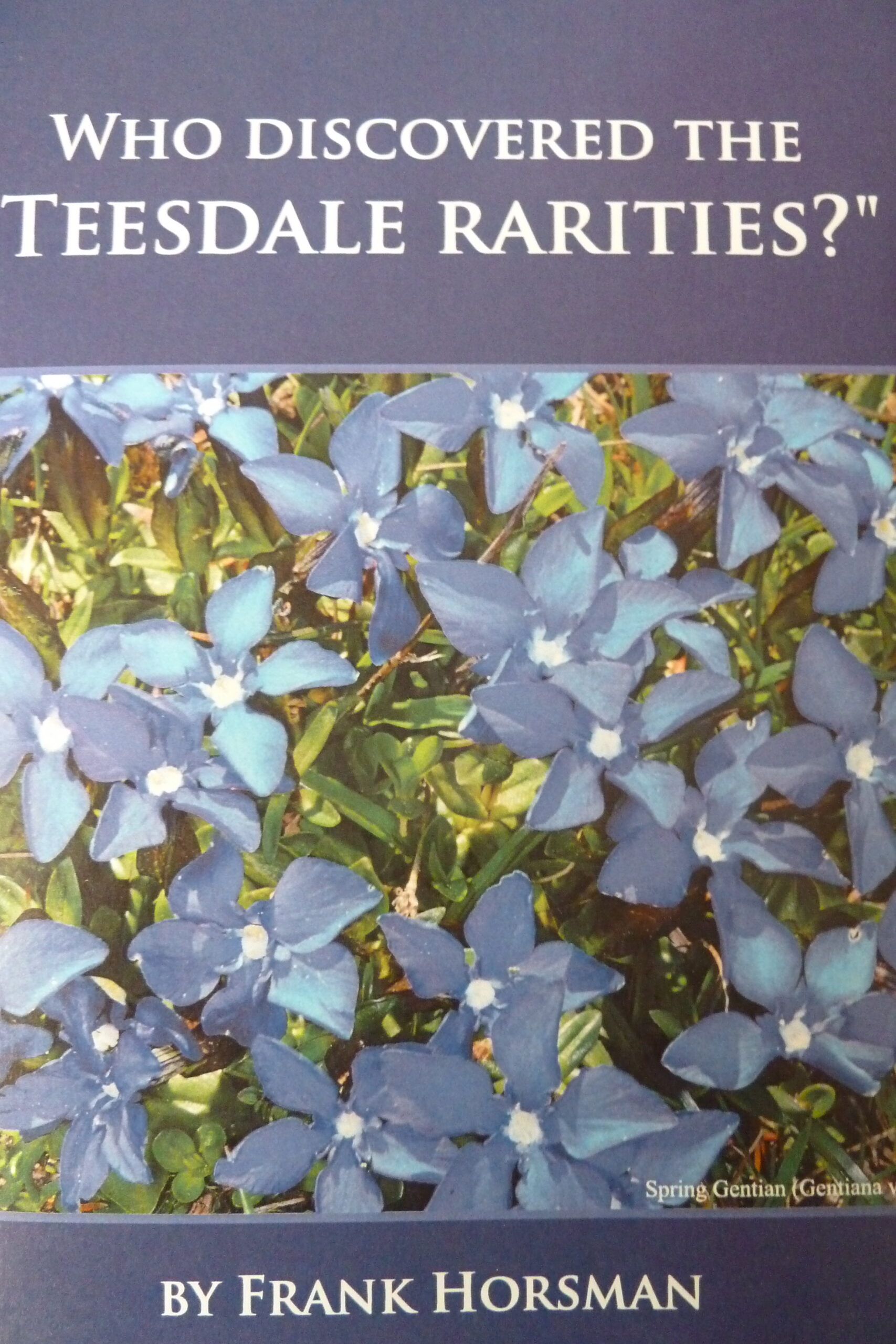

Because the book is self-published efforts have clearly been made to keep costs low. Plates would have enlivened the dense text, but these are only available by going online to access the author’s thesis. This is a real shame as the list of plates provided at the end of the book reveals so much about the sources used, their survival, and significance. The text is condensed, in small print, and additional editorial support might have made the book more accessible; elements of a PhD thesis remain. Nevertheless, as a source of reference for anyone interested in historical botany and the personalities involved in the discovery of Teesdale’s rare plants this book is a marvellous resource. The bibliography is comprehensive, running to seven pages, and the index is excellent, enabling a ready search of the mine of information held within.