Dr Gordon Port introduces the anatomy and life cycle of the North East’s diverse and beautiful ladybirds.

Anatomy

Ladybirds are insects belonging to the Order Coleoptera (the beetles). They have legs and antennae, but often these are difficult to see. Fortunately, most ladybirds can be identified by looking at the colour patterns on three parts of the body (Image 1).

Noting the size, patterning of the pronotum (section between the head and wing cases) and elytral patterning (wing cases) can help you to identify adult ladybirds and separate similar species from each other.

The head bears the compound eyes, the antennae and the mouthparts.

The pronotum is a hard plate between the head and elytra. The colour and patterning on the pronotum is helpful when identifying species and can be more useful than the patterning on the wing cases for some species.

The elytra are the pair of wing-cases that cover the abdomen and typically have spots. Like all beetles the front pair of wings are modified to form the protective elytra. Beneath the elytra are the hind wings which can be unfolded when the ladybirds start to fly. The number, arrangement, shape and colour of the spots on the elytra help with identifying an adult ladybird species.

A more detailed diagram of adult ladybird anatomy is available on the UK Ladybird Survey website here.

Ladybird lifecycle

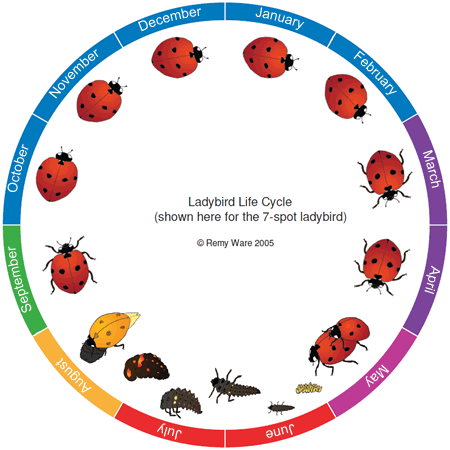

Like the other highly evolved insect groups (butterflies and moths, bees, wasps and ants, flies, and the beetles, which include ladybirds) undergo complete metamorphosis as they develop. That is the eggs hatch into larvae which, when full-grown, moult into pupae and eventually the adults emerge. For most UK ladybirds this life cycle takes a whole year and is illustrated in Image 2.

In warm years some species of ladybird, such as the Harlequin Ladybird, may be able to complete a second generation in the UK. Adult ladybirds overwinter to escape the worst of the winter weather and the limited food supply. Depending on the species, this can start in September and typically lasts until the following March.

Adults are therefore more readily observed from March through to September. Although not active, you can still find and record ladybirds in their overwintering habitats such as in tree crevices and leaf litter. Groups of overwintering ladybirds can often be seen clustered together.

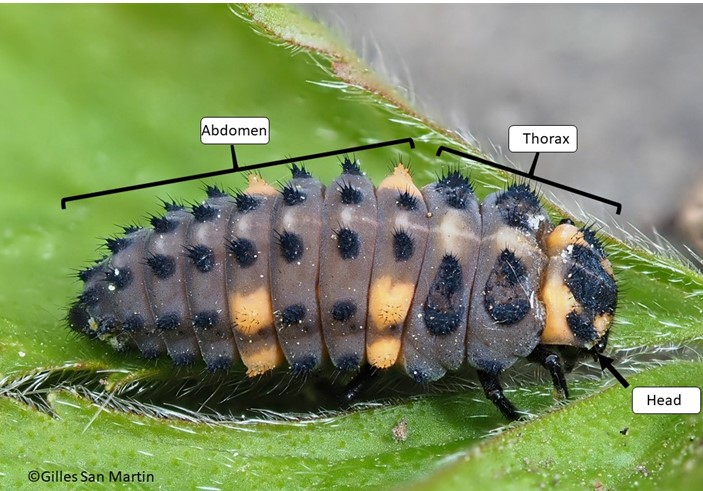

The larvae (Image 3) and pupae (Image 4) of ladybirds look very different from the adults. Larvae tend to have the same food preferences as adults of the same species and feed voraciously.

Larvae in their final stages are relatively easy to identify with the exception of 2-spot and 10-spot Ladybirds. Identifying larvae requires looking at the colour and the patterning on the head, thorax and abdomen.

You may find larvae from June onwards. It is not uncommon at this time of year to find more larvae than adults, as the overwintered adults die off after reproduction.

Noting the colour and markings of the pupae can help you to identify a ladybird in its pupal stage. Sometimes, the remains of larval skin can also assist with identification. Adult ladybirds emerge from the pupae after around one week and it often takes a few days for the characteristic ladybird colours to appear.

More details of the ladybird year are given on the UK Ladybird Survey website.