Get to grips with bee basics as Charlotte Rankin introduces the anatomy, life cycle and key identification features of North East bees.

When getting to grips with bee identification, it is useful to understand the basic parts that make up a bee, their diversity, and key identification features. This article explores what to look out for when observing bees across the North East.

The bee body

Bees have three main body sections: the head, thorax and abdomen.

On their head is a pair of compound eyes, ocelli (sensory organs), antennae and jaws (known as mandibles). Looking at the length of the antennae can help you to distinguish between male and female bees. Males tend to have longer, more curved antennae while females have straighter and shorter antennae.

The thorax is the middle segment of the bee, behind the head and before the abdomen. Attached to the thorax are the six legs and wings. Unlike flies, bees have two pairs of wings. The abdomen is the longest body section and, in females, ends with a stinger. The colour of the hairs on the head, thorax and abdomen can help to identify a bee.

Pollen collection

Females collect pollen and have special pollen-collecting hairs (solitary bees), or pollen baskets (bumblebees and honeybees), to help with this. Female bumblebees collect pollen on their hind legs on special pollen baskets. These appear shiny and black and are often covered in a moist ball of pollen.

Females of most solitary bees collect pollen on their hind legs. Known as a pollen brush or scopa, there are usually dense pollen-collecting hairs on their hind legs. In contrast, leafcutter bees and mason bees have their pollen brush on the underside of their abdomen. As a result, you will often see these bees with undersides covered in brightly coloured pollen. In contrast to bumblebees, the pollen loads of solitary bees appear dry and powdery.

Identifying Bumblebees

Bumblebees live in social nests, with a queen and up to a few hundred worker bumblebees. Nests are usually established in spring and workers build up in number throughout spring and summer. These workers collect nectar and pollen for developing bees back at the nest.

Workers are generally smaller versions of the queen but, in some species, there are also differences in banding or tail colour. Towards the end of a bumblebee nest’s life, the queen starts to produce males and new queens. Males and new queens are therefore commonly observed in late summer.

Tail colour

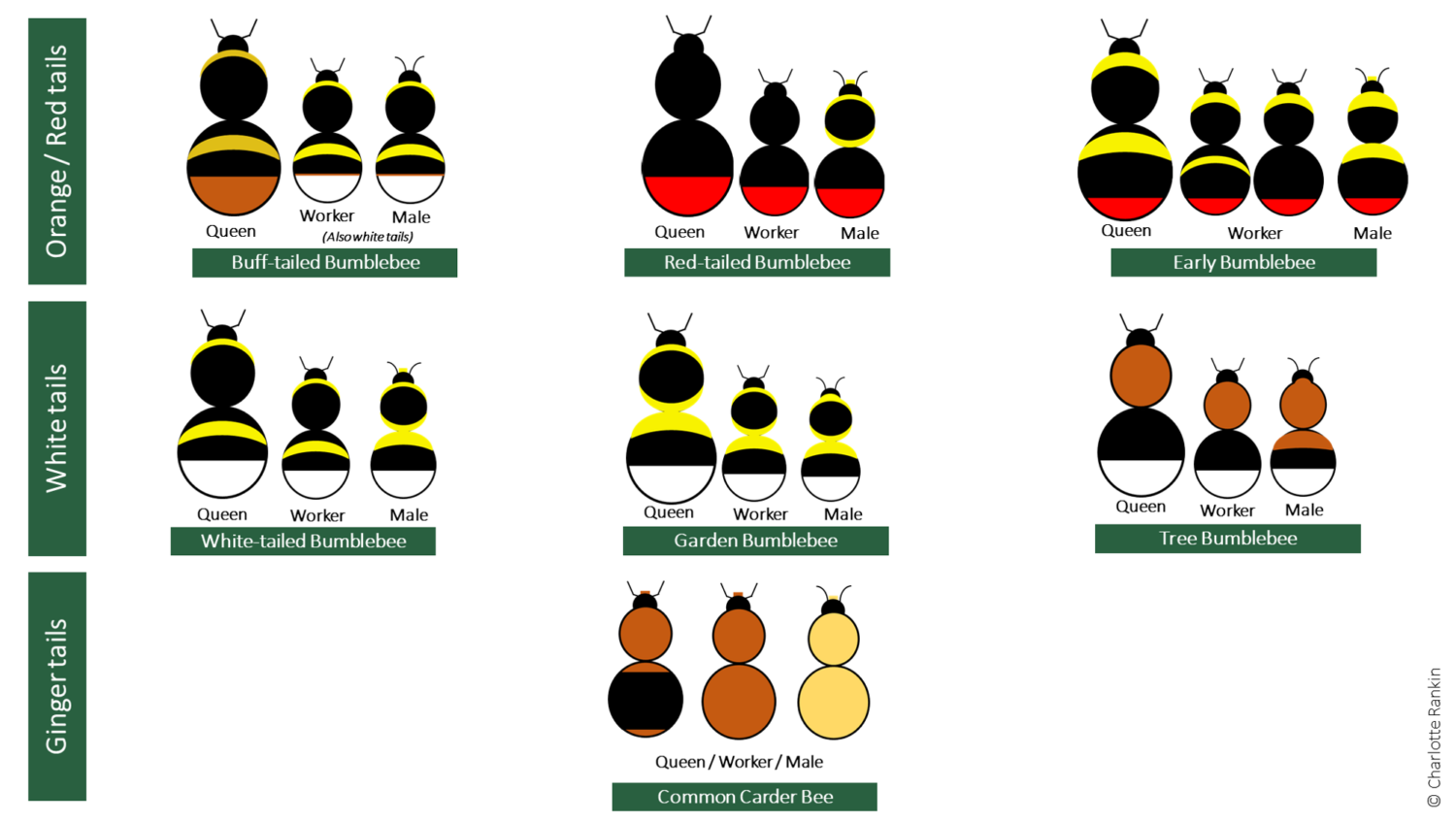

When identifying a bumblebee, a good step is to first identify the colour of the tail: is it white, orange, red or ginger? Your bumblebee can be narrowed down by simply looking at the tail colour.

Hair bands

You can then look at the yellow banding, or absence of banding, on the bumblebee. The number of yellow bands, or absence of banding, can help you to identify the bumblebee species. For example, the Garden Bumblebee (Bombus hortorum) has three yellow bands whereas the White-tailed Bumblebee (Bombus lucorum sensu lato) has two yellow bands.

The Garden Bumblebee and Tree Bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) both have white tails. However, the Tree Bumblebee has no yellow bands. Instead, it can be identified by looking at the hair colour of the thorax (chestnut brown) and abdomen (black with a white tail tip).

Legs

Only female bumblebees collect pollen. Therefore, only females have the shiny black pollen baskets on their hind legs. Males lack these pollen baskets and have hairy back legs.

Face

For some bumblebee species, looking at the face can help. The Garden Bumblebee has a long ‘horse-shaped’ face that is unlike that of any other British bumblebee. Males of some species, including Early Bumblebee, White-tailed Bumblebee and Red-tailed Bumblebee, have distinctive yellow tufts of hair or ‘moustaches’ on their faces.

Cuckoo bumblebee?

Female cuckoo bumblebees take over the nest of other bumblebee species. Looking at the colour and banding of hair also helps to identify cuckoo bumblebees. A good field clue is the the darker, smoky wings and sparser hair. As the females do not collect pollen, their hind legs are also densely haired.

Identifying Solitary Bees

Unlike bumblebees and honeybees, female solitary bees construct and provision their own nests without the help of workers. Nests consist of a series of sealed nest cells, each containing an egg provisioned with nectar and pollen. Males emerge just before the females, who will then mate before the female proceeds to find and establish a nest.

Due to the great diversity of solitary bees, identifying them is less straightforward. However, with practice, it becomes easier to distinguish the different groups of solitary bee. Here are four top tips to help you start with solitary bee ID:

Female or male?

Males are generally smaller and slimmer than females with longer, curved antennae. Females are generally larger and stockier with shorter antennae. If you see a solitary bee with pollen collected on the hind legs or underside of the abdomen, it is definitely a female.

Behaviour also helps too. Males are often seen zooming around nest sites in search for a mate. Males visit flowers only for nectar and you will never see males collecting pollen.

Where is the pollen?

Most female solitary bees collect pollen on their hind legs. In some species, notably the mining bees, it can cover most of the leg as well as the sides of the female. However, if you find a bee with pollen-collecting hairs under the abdomen, this helpfully narrows your bee down to two groups: the leafcutter bees and mason bees. The colour of the pollen brush hairs can help with identification.

Female Hawthorn Mining Bee with pollen load on hind legs

Female Leafcutter Bee with pollen brush on abdomen underside

Where is it nesting?

Most solitary bees are ground-nesters, such as in bare and sparsely vegetated ground. However, some species are aerial-nesters such as in walls and garden bee hotels. Typical groups you will find in your garden bee hotel are species of leafcutter bee, mason bee and yellow-face bee.

Time of year

It is also important to consider the time of year as solitary bees differ in their flight periods. Some solitary bees are spring-flying whilst others emerge in summer. For instance, Red Mason Bees (Osmia bicornis) are spring-flying bees whereas leafcutter bees are out later in summer. The Hairy-footed Flower Bee (Anthophora plumipes) is spring-flying whereas the Fork-tailed Flower Bee (Anthophora furcata) is summer-flying.

Take part in the North East Bee Hunt

Urban or rural, beginner or expert, we need your help to record wild bees across the North East.

Your records can add to our understanding of bees in the region and inform conservation and monitoring efforts.

Taking part is easy and every record counts, wherever you live in the region. Records of all bee species are encouraged.